From the exhibition Now! Hairy Who Makes You Smell Good!, running at the Art Institute of Chicago from September 27, 2018 through January 6, 2019: Jim Nutt. “Now! Hairy Who Makes You Smell Good,” 1968. The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Gladys Nilsson and Jim Nutt. © Jim Nutt.

From the exhibition Now! Hairy Who Makes You Smell Good!, running at the Art Institute of Chicago from September 27, 2018 through January 6, 2019: Jim Nutt. “Now! Hairy Who Makes You Smell Good,” 1968. The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Gladys Nilsson and Jim Nutt. © Jim Nutt.

“Free speech is the right to shout ‘theater’ in a crowded fire.”

— A Yippie proverb, cited by Abbie Hoffman — a member of the Chicago Seven arrested and charged, along with Tom Hayden and others, after protesting at the Democratic convention held in Chicago during the Summer of 1968 — in “Steal This Book” (Pirate Editions, distributed by Grove Press)

Introduction by Paul Ben-Itzak

Text from Experiments in Prose,

Edited by Eugene Wildman

Copyright 1969 The Swallow Press, Chicago

Illustrated with images from the current or upcoming Art Institute of Chicago exhibitions Now! Hairy Who Makes You Smell Good!, Past Forward: Architecture and Design at the Art Institute, and Never a Lovely So Real: Photography and Film in Chicago, 1950–1980

(Editor’s note, explanatory: The inclusion of the images from the Art Institute of Chicago exhibitions should not imply any association of the artists with the views expressed. Rather, this Chicago mix tape is intended to reflect the kaleidescopic brilliance of the multiplicity of Chicago schools of thought, literature, art, architecture, and design.)

(Editor’s note, prosatory: In dockside picnics looking out on Lake Michigan while on cross-country train trip pauses, in dreams of ame-soeurs encountered on busses crossing the lake’s glittering sea-like azure expanse, on a Sunday morning jog after an interview for a position I was offered but didn’t take (after my future boss had handed me a press release announcing a new version of Prozac for dieters and explained “Your role would be to analyze how the news will affect the stock” and I’d thought “No, I’d be more concerned with how the product might affect the dieter”) where I ran smack dab into the final leg of the Chicago Marathon and was cheered on by bystanders as if I’d run the whole race, standing before Chagall’s “White Jesus,” a refugee from Hitler’s “Degenerate Art” exhibition, with its burning synagogues, in the cool halls of the Art Institute near the banks of the Chicago River, peering at a river-boat from the parapet of a bridge named after Hull House’s Jane Addams, contemplating, in a Paris museum, Henry Darger’s epic saga of the Viviane Girls, drawn to accompany a 15,000-page manuscript discovered in Darger’s humble janitor’s quarters in Lincoln Park before it became chic, sipping beers on the mahogany counter of a former speakeasy in the same ‘hood converted to a friend’s living room, whisked back to the train by a brisk autumnal wind while a lone saxophonist breathes life into the canned Debussy piped into a downtown district, seeing African-American workers being shooed away from a private lunch table set up in the publicly-owned Union Station, being held up at a corner outside the station for a police car chase which I soon learn was rigged for a film shoot, and contemplating a mayor, Rahm Emanuel, who seems mostly interested in privatizing city services, roads, and schools, and where the Black population in one of the most segregated cities in the country has dropped by 250,000, aspiring to continue in the spirit of Izzy Stone, and above all inspired by Nelson Algren’s “Chicago, City on the Make” — a screed which has the sentimental effect of an homage — Chicago has always haunted and hounded me. So I was not at all surprised when, in July 2016, about to cross the flooded Seine, my other favorite body of water, I discovered, on a bench not far from a bookstand, “Experiments in Prose,” a celebration of the free-spirited Chicago-style design, literature, and activism which flourished in the 1960s produced by former Chicago Review editor Eugene Wildman for the Chi-based Swallow Press, and which opens with:

Talking

(Tape by Bruce Kaplan. Recorded primarily in the Lincoln Park area of Chicago during the 1968 Democratic National Convention and Mayor Daley’s triumph of the will.)

(From a poem about 80 lines long.)

… America, today you are a Helen

Helen, in your old age, in your wisdom

Is it to be a policy to war?

…. Your wisdom of war is too deep for me

My mind’s eye cannot see the point of what all this killing is for

Mankind from A to Z , can you see this is our time

World leaders of men, you have read the history of mankind

Why do you waste our time in war…..

That’s a very moving speech. Would you like to say what you were telling me earlier?

Well, I was for Senator Robert F. Kennedy. I had the feeling that he would have been the best to lead all the American people to a greater democracy. He would have helped the minority, the last minority, of Americans, the Negro, to get a fair share of the pie because free enterprise is… a pie, everyone wants a piece of it. I wrote some poems on Chicago too, on Kennedy for the people of Chicago….

From the exhibition Never a Lovely So Real: Photography and Film in Chicago, 1950–1980, running through October 26 at the Art Institute of Chicago: Darryl Cowherd. “Blackstone, Woodlawn/Chicago,” 1968. The Art Institute of Chicago. Through prior gifts of the Harold and Esther Edgerton Family Foundation and Anonymous. © Darryl Cowherd.

You say you gave up your job to write the long one, the Kennedy speech?

Yes and uh it was my own idea, it wasn’t that I was asked to do it, but just that I want to see a greater country and after Senator Kennedy’s passing, I thought that the next best man would be Senator Eugene McCarthy.

What’s your opinion of all these people coming here to Lincoln Park?

Well I think it’s the greatest uh thing to see the young people seeing America, discovering it, there’re young, they’re going all about the country and seeing it, and they want a chance to uh participate in their democracy. It’s a sad thing to see that so many political men have held on to power for close to fifty years, not one of them has [the] grace to bow out and let the younger lawyers and other young men into the government. They hold on with one foot in the grave, they still refuse to bow out gracefully. My name is John F——-, Irish-American, 38 years old, seven months in Chicago from New York City, eighth grade education.

MAN, AMERICA, MANKIND

I stand here before you a man

Not with the idea to teach you

That I cannot do, for I have learned from you

Shakespeare still is a poet, and a painter, and a musician….

I worked very hard on that. You see, Kennedy loved Aristotle, and all the great poets, see, and I reached in for Helen of Troy because Helen of Troy was so beautiful that they all went to war.

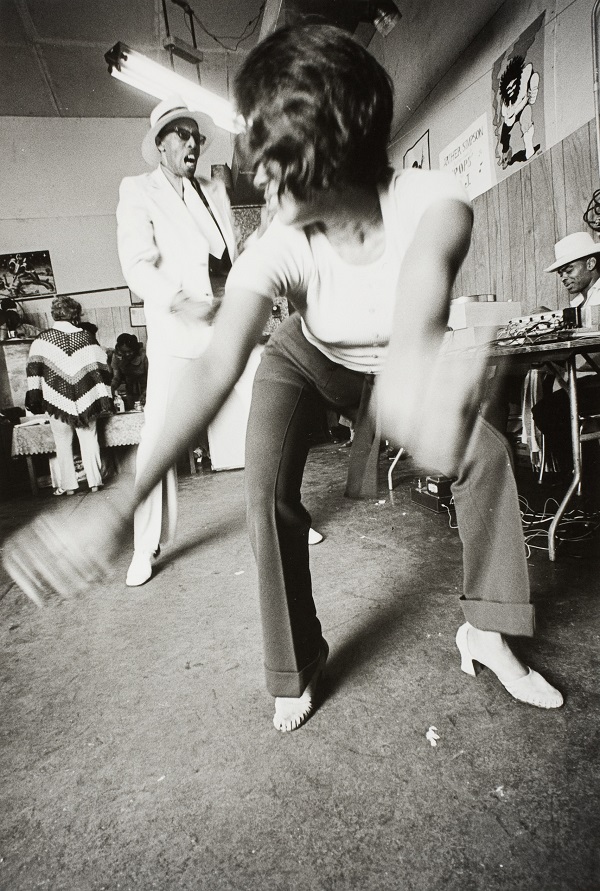

From the exhibition Never a Lovely So Real: Photography and Film in Chicago, 1950–1980, running through October 26 at the Art Institute of Chicago: Valeria “Mikki” Ferrill, Untitled from The Garage, 1972. The Art Institute of Chicago. National Docent Symposium Endowment. © Mikki Ferrill.

(Group of girls.)

We’re carrying nothing that hasn’t proved its practicality and necessity by several years of experience. The heavy jeans and turtleneck are protection against mace, likewise the vaseline. The tape on the glasses to keep from getting hit on the glasses. The helmet liner is to protect the head. We tested these helmet liners last night by beating each other over the head with metal vases. The gas mask is again against mace or tear gas or worse, which they are using. For instance, that tear gas shell that exploded in Soldiers Field last night, they mentioned powdered irritants injuring police and National Guard, well come on there are no powdered irritants in mace or tear gas. That had to be something else.

They laid three of them up in the hospital. Probably military and domestic reagents. (?)

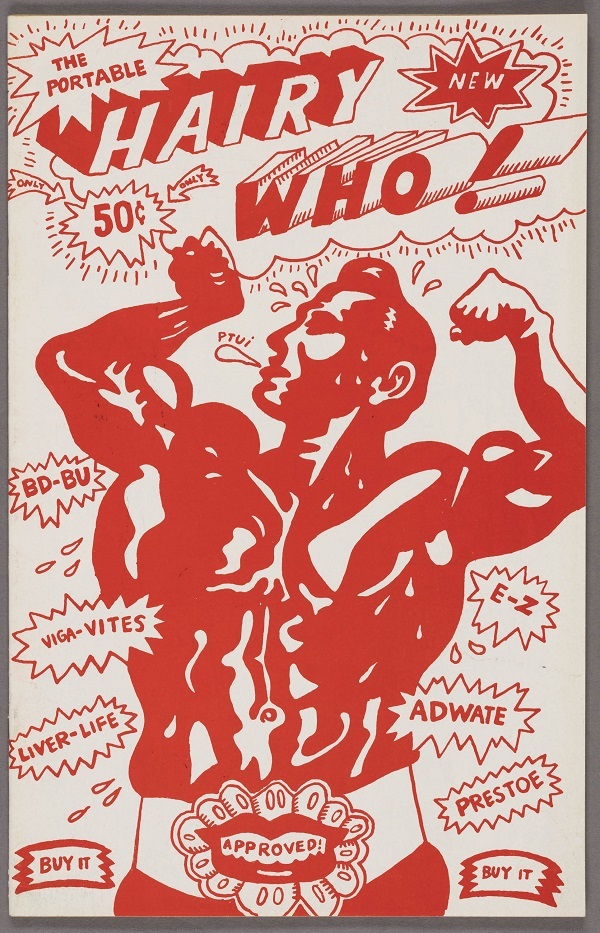

From the exhibition Now! Hairy Who Makes You Smell Good!, running at the Art Institute of Chicago from September 27, 2018 through January 6, 2019: Jim Falconer, Art Green, Gladys Nilsson, Jim Nutt, Suellen Rocca, and Karl Wirsum. “The Portable Hairy Who!,” 1966. The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Gladys Nilsson and Jim Nutt.

All right what else are we carrying….

Is the radio necessary?

That’s just to follow the news. The medical kit for obvious reasons, bandages, iodine, alcohol for mace. We have a half pint of absolute grain alcohol. The fact is, something that was bitterly learned at Ann Arbor, where we’re from, is that if you are blind drunk mace will not touch you.Time and again they have tried to subdue mad drunks with mace and wound up with a bunch of maced cops and a mad drunk.

Do you have any idea why that is true?

No idea why it’s true, just that it works. For the same reason that we don’t know how mace suppresses the part of your metabolism that digests vitamins. It does, that’s one of the effects of it. These are army surplus gas masks. You can get them for eleven dollars at the Army surplus store on Barry Street. You have to frighten them into giving them to you because the police have talked them out of selling gas masks. The World War II gas masks have been bought up by the fire department; these are World War I. Ah, but they’ll work. The black is because the worst of the police brutality is after dark, they seem to feel bolder in the dark, therefore the black is to protect you. You can hide easier.

From the exhibition Never a Lovely So Real: Photography and Film in Chicago, 1950–1980, running through October 26 at the Art Institute of Chicago: Billy Abernathy, “Mother’s Day,” from “Born Hip,” 1962. The Art Institute of Chicago. Gift of the Illinois Arts Council.

From the exhibition Never a Lovely So Real: Photography and Film in Chicago, 1950–1980, running through October 26 at the Art Institute of Chicago: Billy Abernathy, “Mother’s Day,” from “Born Hip,” 1962. The Art Institute of Chicago. Gift of the Illinois Arts Council.

You obviously feel there is a great deal of danger in coming to Chicago. Why did you?

We have had the word from some of our friends in New York, who were in Washington, and looked over the situation here, that we ought to have helmets, gas masks, and the works. The usual reaction by the police is not in regard to any action taken by the demonstrators, rather in accordance to the size of the crowd — the bigger the crowd the much more likely the possibility of police violence. This has been proved over and over again. The marchers don’t have to start anything, just a sizeable enough crowd will incite them. For instance, already two people here, that brings the count to what seven so far? In the past three days. And this is before anything’s even started.

Three killed, four injured, so far.

There was a guy killed last Thursday?

Dean Johnson and two others.

Who were the others killed?

I’m not sure, I don’t have all the information….

It was in the papers but we had to leave the papers and everything back because we can’t carry anything that isn’t absolutely essential. Oh, this uh experience too, the name of the defense fund. These are so that if I get hit on the arms I won’t get my wrists cut.

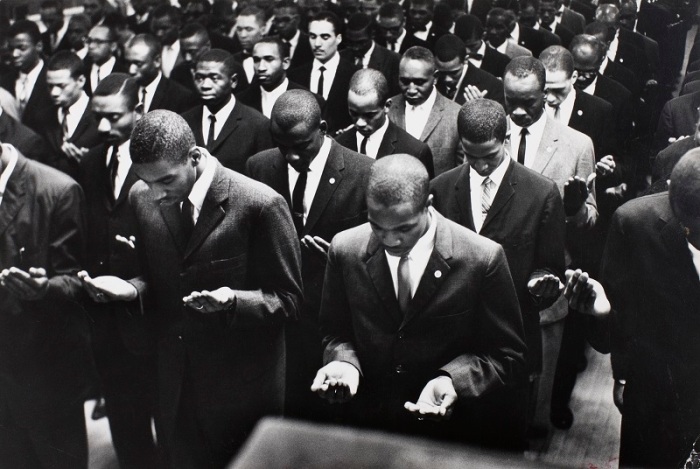

From the exhibition Never a Lovely So Real: Photography and Film in Chicago, 1950–1980, running through October 26 at the Art Institute of Chicago: Gordon Parks, Untitled, Chicago, Illinois, 1963. The Art Institute of Chicago. Anonymous gift. © The Gordon Parks Foundation.

From the exhibition Never a Lovely So Real: Photography and Film in Chicago, 1950–1980, running through October 26 at the Art Institute of Chicago: Gordon Parks, Untitled, Chicago, Illinois, 1963. The Art Institute of Chicago. Anonymous gift. © The Gordon Parks Foundation.

What’s worth the risk…. Why are you here?

Freedom man.

Freedom man, that’s all there is. Freedom’s where it’s at. We gotta get it.

What’s frightening now is not so much that the uh…. What’s really terrifying in the world situation today is how much we’ve become like the Soviet Union. As much as them like us, we like them. The same people that are demonstrating against Vietnam are now demonstrating against Czechoslovakia. It’s the exact same thing. One of our favorite anti-Vietnam people in New York is out throwing rocks at the Russian embassy.

I heard some people standing around talking before, fairly straight looking, saying it looked like the newsreels from Prague.

Incidentally, we found out who the federal allies they brought in are, the Eighty-Second Airborn, the one that was used at the Pentagon, the Dominican Republic, and Vietnam. What they do when they train people, it’s for riot training, what they do we found is they give them all sorts of stuff about these kids are all Commie agitators trying to stir up, etc etc. which is so much bull. Honestly there’s nobody quite like SDS [Students for a Democratic Society], the New Left, and so on for throwing out Marxists wherever they find them. [In the early 1980s, reports surfaced that SDS had been infiltrated by government agents.] That happened at the last convention and they’re throwing them out steadily. The actual number of SDS people here is rather small. You’d be surprised, not all SDS members carry cards. Most of them are in other organizations too; it’s an interlocking thing.

Why do you think so many fewer people have come to Chicago than everybody was saying?

Nothing about it makes sense….

***

Those are the grooviest helmets I ever saw.

Thanks. Would you believe that more than half the people in this coutnry have no vote, no voice, and this is what we’re protesting. We can’t vote in the ballot box, we can’t get our words in a magazine, in the papers, all we can do is bring our bodies to the demonstrations, and vote that way. If we’re not given a voice, not listened to, well the imbalance remains and there’s only one way to correct it, we hope it won’t come to that. It has happened before.

What’s that?

It’s water, just water. Water is the one good antidote for mace. The vaseline will keep the mace out, but the water will wash off the vaseline. The water’s to get the mace out once it’s in your face.

From the exhibition Past Forward: Architecture and Design at the Art Institute, now running at the Art Institute of Chicago: Stanley Tigerman, “The Titanic, 1978.” The Art Institute of Chicago. Gift of Stanley Tigerman. © 1978 Stanley Tigerman.

From the exhibition Past Forward: Architecture and Design at the Art Institute, now running at the Art Institute of Chicago: Stanley Tigerman, “The Titanic, 1978.” The Art Institute of Chicago. Gift of Stanley Tigerman. © 1978 Stanley Tigerman.

Revolution brothers….

(in unison) Revolution… si … black flag, great…. By the way, anarchy and chaos are not the same thing if anyone wants to know. We’ve been saying it for years but who listens to us, once again. The whole idea behind the anarchy thing here is simply that people will by themselves without outside control….

…. These men have a hitherto untested capacity for self direction….

They will, on their own, order their own society. People don’t need the whip, what they carry is enough, that’s what we’re fighting for, why we to take all the whips out of society, there’re garrets enough. People will naturally form an order and stick to it, and when they can’t, well, society sure as hell can’t do it for them. Society’s supposed to serve man, not vice versa.

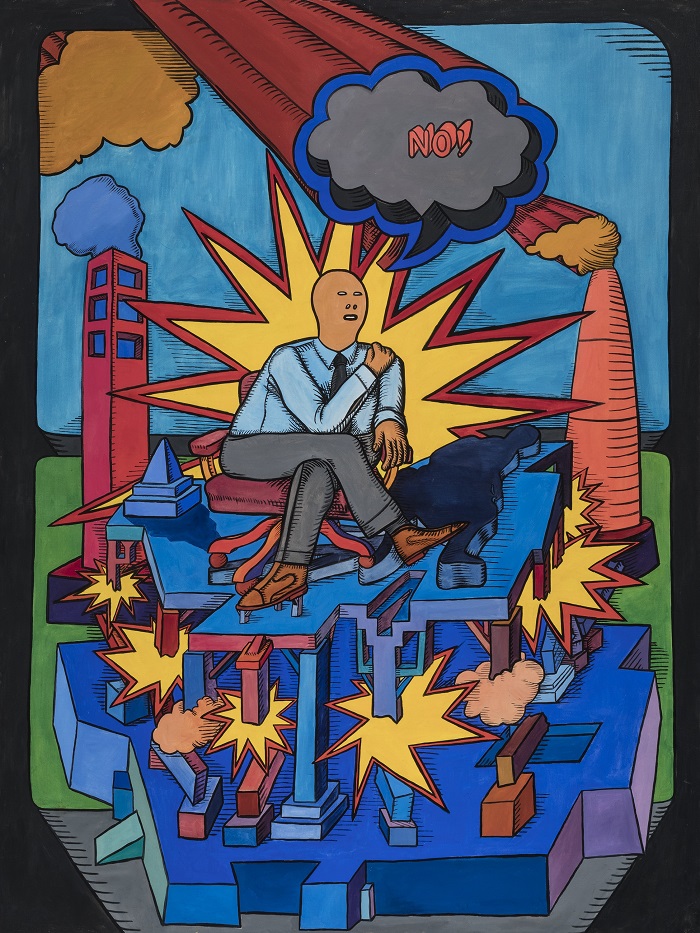

From the exhibition Now! Hairy Who Makes You Smell Good!, running at the Art Institute of Chicago from September 27, 2018 through January 6, 2019: Art Green. “Consider the Options, Examine the Facts, Apply the Logic (originally titled The Undeniable Logician),” 1965. Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, Anonymous Gift. © Art Green.

From the exhibition Now! Hairy Who Makes You Smell Good!, running at the Art Institute of Chicago from September 27, 2018 through January 6, 2019: Art Green. “Consider the Options, Examine the Facts, Apply the Logic (originally titled The Undeniable Logician),” 1965. Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, Anonymous Gift. © Art Green.

From the exhibition Never a Lovely So Real: Photography and Film in Chicago, 1950–1980, running through October 26 at the Art Institute of Chicago: Bob Crawford, Untitled (Wall of Respect), 1967. The Art Institute of Chicago. Through prior gifts of Emanuel and Edithann M. Gerard and Mrs. James Ward Thorne. © Bob Crawford/ courtesy Romi Crawford.

From the exhibition Never a Lovely So Real: Photography and Film in Chicago, 1950–1980, running through October 26 at the Art Institute of Chicago: Bob Crawford, Untitled (Wall of Respect), 1967. The Art Institute of Chicago. Through prior gifts of Emanuel and Edithann M. Gerard and Mrs. James Ward Thorne. © Bob Crawford/ courtesy Romi Crawford.

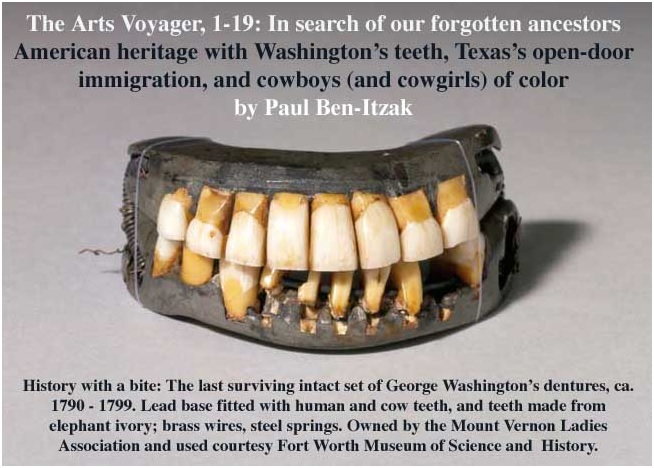

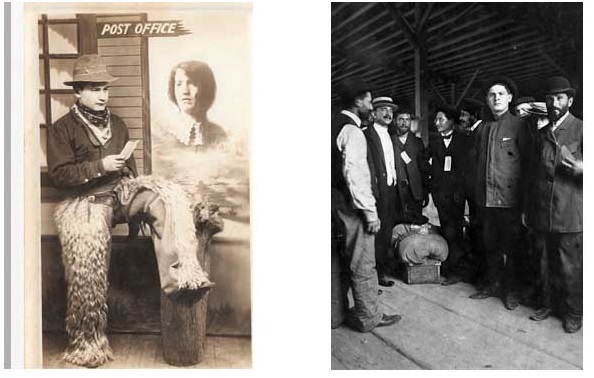

From the exhibition Forgotten Gateway: Coming to America Through Galveston Island. Images courtesy Fort Worth Museum of Science and History.

From the exhibition Forgotten Gateway: Coming to America Through Galveston Island. Images courtesy Fort Worth Museum of Science and History.

Belarus Free Theare in “Being Harold Pinter.” Photo copyright Alexandr Paskannoi.

Belarus Free Theare in “Being Harold Pinter.” Photo copyright Alexandr Paskannoi.

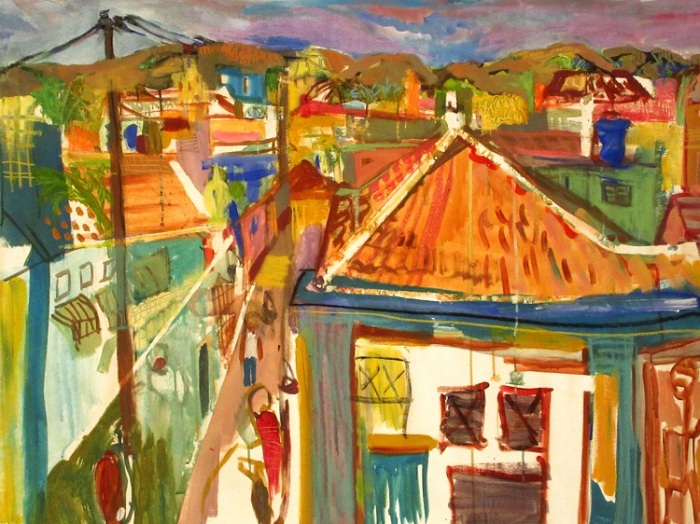

This afternoon on French public radio, a high school student said that if she could vote in next May’s presidential election, she’d choose the Front National, because at least Martine Le Pen’s party would close the borders and keep the foreigners out so they’d stop attacking France. (Never mind, as a classmate pointed out, that the majority of those who have massacred more than 236 French and other nationals over the past two years here have been French.) All the more reason to give thanks for associations that continue to champion crossing borders and frontiers like the Ateliers d’Artistes de Belleville and L’Un dans l’Autre, the former of which is hosting an exhibition of the fruits of the latter’s May residence and collaboration with the Cuban artists of the Espacio Altamira in Havana. The exhibition runs December 8 – 11 in the AAB’s gallery at 1 rue Picabia in Belleville, Paris, with an opening night vernissage from 7 p.m. on. Featured artists include: Guillaume Berga, Luis Blanco, Sigolène de Chassy, Jorge Braulio Rodríguez, Jean-Christophe Cibot, Edel Bordon, Sarah Dugrip, Pablo Victor Bordon Pardo, Nicolas Dupeyron, Ignacio Carballo, Laurence Geoffroy, Michel Deschapells, Patrizia Horvath, Inès Garrido, Hector D. Palacios, Raul Villullas, Yamilé Pardo, Aissa Santiso, and Catherine Olivier, an Arts Voyager

This afternoon on French public radio, a high school student said that if she could vote in next May’s presidential election, she’d choose the Front National, because at least Martine Le Pen’s party would close the borders and keep the foreigners out so they’d stop attacking France. (Never mind, as a classmate pointed out, that the majority of those who have massacred more than 236 French and other nationals over the past two years here have been French.) All the more reason to give thanks for associations that continue to champion crossing borders and frontiers like the Ateliers d’Artistes de Belleville and L’Un dans l’Autre, the former of which is hosting an exhibition of the fruits of the latter’s May residence and collaboration with the Cuban artists of the Espacio Altamira in Havana. The exhibition runs December 8 – 11 in the AAB’s gallery at 1 rue Picabia in Belleville, Paris, with an opening night vernissage from 7 p.m. on. Featured artists include: Guillaume Berga, Luis Blanco, Sigolène de Chassy, Jorge Braulio Rodríguez, Jean-Christophe Cibot, Edel Bordon, Sarah Dugrip, Pablo Victor Bordon Pardo, Nicolas Dupeyron, Ignacio Carballo, Laurence Geoffroy, Michel Deschapells, Patrizia Horvath, Inès Garrido, Hector D. Palacios, Raul Villullas, Yamilé Pardo, Aissa Santiso, and Catherine Olivier, an Arts Voyager