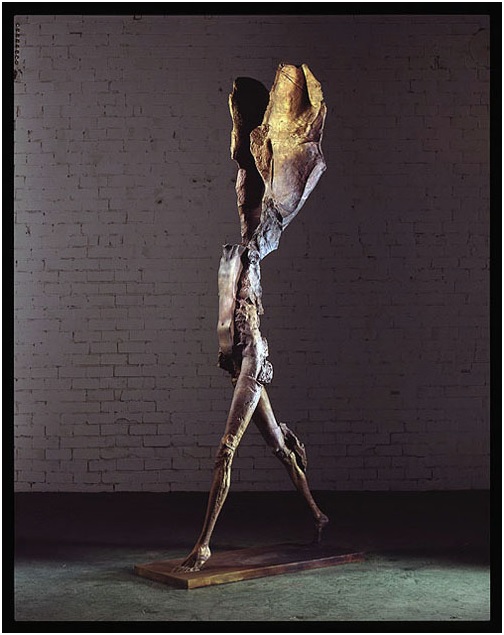

Stephen De Staebler’s “Winged Woman Walking X,” 1995, Bronze, AP/UC, 112 x 20 x 49 inches. Photo by Scott McCue.

By and copyright 2011, 2017 Paul Ben-Itzak

(First published on May 26, 2011.)

I guard an image from the mid-1960s of Stephen De Staebler in a weathered, paint-splattered grey sweatshirt, sleeves bunched up around the elbows, jeans, white sneakers, glasses slightly ajar — a souvenir accompanied by the silty scent of wet clay and dry ceramic dust, Steve’s studio nestled among the tall dense cypress trees in the Berkeley Hills cluttered with works in progress and slabs of sandy, moist, and drying clay arrayed haphazardly on tables. If early encounters with art are critical in determining lifelong interest — I was a kid and used to roughhouse with Steve’s son, Jordan — this one, coupled with public school art classes from another master, Ruth Asawa , did it for me, seeing sculpture first in process and not as dead matter in a stuffy museum. (And in those days, San Francisco’s De Young museum seemed more devoted to dusty relics than the vibrant California School flourishing outside its granite doors.) Over the next 50 years, De Staebler’s work would make it into leading museums and galleries around the world and, most crucially for its integration into the popular imagination, public spaces including the Embarcadero and Concord Bay Area Rapid Transit stations, where his soulful sculptures became part of the landscape even as they elevated it. Compared to painting, my preferred medium as an observer, sculpture often seems to me to be flat and immobile, less vivid and isolated, conversely trapped in time even as in principle it occupies more space and in matter weighs more than a painted canvas. But De Staebler’s work, in ceramic as well as bronze, does not just occupy three dimensions but has a vivacity which seems to animate it.

Kenneth Baker, the influential long-time art critic for the San Francisco Chronicle, wrote in his obituary of Stephen, who died May 13 at the age of 78 from cancer, “Mr. De Staebler, like his mentor Peter Voulkos (1924-2002), helped to reposition ceramic materials and techniques from the critical abjection of ‘mere craft’ to media of major ambition in contemporary sculpture.” The key word here is ‘ambition.’ Without taking anything away from those who simply excel in a particular form, those with the ambition to expand it leave a self-perpetuating legacy beyond their own work, an inheritance for those who succeed them, and that extends its impact on the public beyond their own oeuvre. You can see representations of more of De Staebler’s work on his studio’s website, and the work itself in a major retrospective at the M.H. de Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco, January 14 – April 22. In addition to his artistic creations, Stephen De Staebler is survived by his second wife Danae Lynn Mattes (his first, Jordan’s mother Donna Merced Curley, passed away in 1996), their daughter, Arianne Seraphine, and his sons, Jordan Lucas and David Conrad De Staebler. A memorial will be held sometime in late July at Berkeley’s Holy Parish, whose interior was designed by De Staebler.