Poster designed by Michèle Forgues and Federica Nadalutti, and courtesy Ateliers d’Artistes de Belleville. Click here to read the Arts Voyager’s coverage of last year’s Open Studios / Portes Ouvertes de Belleville, and here to read our essay around the 2010 edition. And for more details on this year’s version, go here.

Poster designed by Michèle Forgues and Federica Nadalutti, and courtesy Ateliers d’Artistes de Belleville. Click here to read the Arts Voyager’s coverage of last year’s Open Studios / Portes Ouvertes de Belleville, and here to read our essay around the 2010 edition. And for more details on this year’s version, go here.

Category Archives: Ateliers Paris

Sponsor Ads Available for Arts Voyager Spring & Summer Paris coverage

Affordably-priced Sponsor ads are now available for the Arts Voyager’s upcoming coverage of performances and exhibitions from all over the world coming to Paris this Spring and Summer. Rates start at just $69 when you sign up before May 15. For more information, e-mail paulbenitzak@gmail.com by pasting that address into your e-mail browser.

Europe at the Crossroads: Portes Ouvertes de Belleville & the Prè Saint-Gervais, Performers from Around the World — Artists Converge on Paris; Help the Arts Voyager be there

Parce que oui, la Culture française – comme d’ailleurs tous les cultures qui déferle vers Paris – appartient au monde qu’elle a si souvent rayonné, et il faut refusé de la laisse etre confiné et sequestré par les forces de l’Obscurantisme.

For subscription and sponsorship opportunities starting at $69, contact Paul Ben-Itzak at artsvoyager@gmail.com.

The Open Studios or Portes Ouvertes de Belleville and those of the Prè Saint-Gervais, performers including Berlin’s Constanza Macras, Portugal’s Vera Mantero, a major exhibition devoted to Camille Pissarro paintings rarely seen in France, Belgium’s Alain Platel, Spain’s Israel Galvan, Crystal Pite — these are just a few of the major cultural happenings in Paris and environs this Spring that the Arts Voyager and Dance Insider will be able to cover with your support.

Many of you first read about these internationally renowned artists and events for the first time in English in our journals and, continuing our 20-year mission of bringing you stories not told elsewhere, we’ll also be reporting on Giulio D’Anna, a Netherlands-based Italian choreographer whose “OOOOOOO” is inspired by Zagreb’s “Museum of Broken Relationships,” and Jasna Vinovrski’s “Lady Justice,” addressing the relationship between justice and art. Speaking of art, we’d also like to bring you Yasmina Reza’s “Art” as interpreted at the Theatre de la Bastille by the pioneering Belgium theater company STAN . And of intersections between art and society, this year’s Chantiers (Building Projects) d’Europe festival at the Theatre de la Ville features countries in the front lines of the refugee crisis, notably in six short films from Greece addressing this topic and a public brainstorming session with artists from six countries. Most of all we’ll be able to bring you into the studios of the 200+ artists taking part in the Open Studios of Belleville — a neighborhood which in its very MULTI-CULTURAL contours and dimensions provides the best retort to the cloistered vision of French culture represented by the National Front. (We share the FN’s stated pride in traditional French culture; we simply argue that this definition is too limited and does not do justice to the grandeur and ouverture to the world that has always been French culture.) Click here to read our coverage of last year’s Open Studios / Portes Ouvertes de Belleville.

Already a subscriber or sponsor? Please forward this story to your colleagues. Want to become one? Contact us at paulbenitzak@gmail.com . Subscribers receive full access to our 20-year archive of more than 2,000 reviews by 150 leading artist-critics of performances on five continents, plus five years of the Jill Johnston Letter as well as Arts Voyager art galleries, film reviews, and travelogues from Paris, New York, and across the U.S.. Sponsors receive this plus advertising on The Dance Insider, and/or the Arts Voyager.

France, too, is at the crossroads. On May 7 the country will choose between the fear represented by the National Front and the hope and optimism represented by Emmanuel Macron. Between closure and opening. In the campaign between these two ‘cultures’ that has raged in this country for the past two years, CULTURE has been all but forgotten. (Among Macron’s refreshing ideas: More library hours.) With your help, we will be able to do our part in restoring some light to what has always been France’s principal calling card around the world. Our calling for more than 20 years.Many thanks and

Cheers,

Paul

artsvoyager@gmail.com

Subscribe!

Subscribe to the Dance Insider & Arts Voyager today for just $29.95/year or 29.95 in Euros and get complete access to our 20-year archive of more than 2,000 exclusive reviews of performances and exhibitions on five continents by 150 writers, plus Paul Ben-Itzak’s commentaries on the Paris and New York scenes, art, Jill Johnston & more. Just designate your PayPal payment in that amount to paulbenitzak@gmail.com , or write us at that address to find out about payment by check. Institutional rate of $99 or 99 Euros/year gets full access for your entire company, school, etcetera. Sponsorships start at just $49/month and include placements like that above of DI sponsor Freespace Dance. Photo of Freespace Dance’s Donna Scro Samori and Omni Kitts by and copyright Lois Greenfield. Sign up as a sponsor before May 1, 2017 and receive a second month free. Contact paul@danceinsider.com .

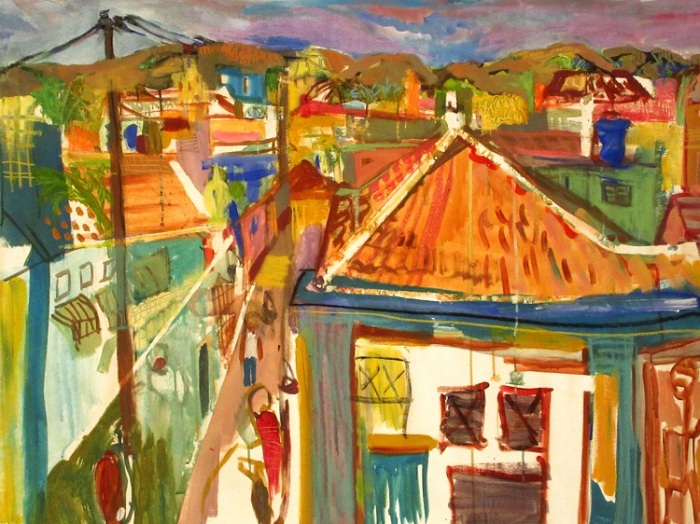

This afternoon on French public radio, a high school student said that if she could vote in next May’s presidential election, she’d choose the Front National, because at least Martine Le Pen’s party would close the borders and keep the foreigners out so they’d stop attacking France. (Never mind, as a classmate pointed out, that the majority of those who have massacred more than 236 French and other nationals over the past two years here have been French.) All the more reason to give thanks for associations that continue to champion crossing borders and frontiers like the Ateliers d’Artistes de Belleville and L’Un dans l’Autre, the former of which is hosting an exhibition of the fruits of the latter’s May residence and collaboration with the Cuban artists of the Espacio Altamira in Havana. The exhibition runs December 8 – 11 in the AAB’s gallery at 1 rue Picabia in Belleville, Paris, with an opening night vernissage from 7 p.m. on. Featured artists include: Guillaume Berga, Luis Blanco, Sigolène de Chassy, Jorge Braulio Rodríguez, Jean-Christophe Cibot, Edel Bordon, Sarah Dugrip, Pablo Victor Bordon Pardo, Nicolas Dupeyron, Ignacio Carballo, Laurence Geoffroy, Michel Deschapells, Patrizia Horvath, Inès Garrido, Hector D. Palacios, Raul Villullas, Yamilé Pardo, Aissa Santiso, and Catherine Olivier, an Arts Voyager featured artist who took the bottom copyrighted photo of the collective work “Trinidad.” The top photo of the collective work “La Rampa” was taken by and is copyright Sarah Dugrip. — Paul Ben-Itzak

This afternoon on French public radio, a high school student said that if she could vote in next May’s presidential election, she’d choose the Front National, because at least Martine Le Pen’s party would close the borders and keep the foreigners out so they’d stop attacking France. (Never mind, as a classmate pointed out, that the majority of those who have massacred more than 236 French and other nationals over the past two years here have been French.) All the more reason to give thanks for associations that continue to champion crossing borders and frontiers like the Ateliers d’Artistes de Belleville and L’Un dans l’Autre, the former of which is hosting an exhibition of the fruits of the latter’s May residence and collaboration with the Cuban artists of the Espacio Altamira in Havana. The exhibition runs December 8 – 11 in the AAB’s gallery at 1 rue Picabia in Belleville, Paris, with an opening night vernissage from 7 p.m. on. Featured artists include: Guillaume Berga, Luis Blanco, Sigolène de Chassy, Jorge Braulio Rodríguez, Jean-Christophe Cibot, Edel Bordon, Sarah Dugrip, Pablo Victor Bordon Pardo, Nicolas Dupeyron, Ignacio Carballo, Laurence Geoffroy, Michel Deschapells, Patrizia Horvath, Inès Garrido, Hector D. Palacios, Raul Villullas, Yamilé Pardo, Aissa Santiso, and Catherine Olivier, an Arts Voyager featured artist who took the bottom copyrighted photo of the collective work “Trinidad.” The top photo of the collective work “La Rampa” was taken by and is copyright Sarah Dugrip. — Paul Ben-Itzak

Art not Bombs: In Artcurial Impressionism & Modern Auction, Hope

Georges Papazoff (1894-1972), “Tete,” circa 1928. Oil on canvas, 92 x 73 cm (36 1/4 x 28 3/4 inches). Signed at lower left. Pre-dates by 17 years Duchamp’s intergallactic View cover. Artcurial pre-sale estimate 20,000 – 30,000 Euros. Image copyright and courtesy Artcurial.

Georges Papazoff (1894-1972), “Tete,” circa 1928. Oil on canvas, 92 x 73 cm (36 1/4 x 28 3/4 inches). Signed at lower left. Pre-dates by 17 years Duchamp’s intergallactic View cover. Artcurial pre-sale estimate 20,000 – 30,000 Euros. Image copyright and courtesy Artcurial.

Ferdinand du Puigaudeau (1864-1930), “Jeune fille à la bougie,” 1891. Oil on thin cardboard laid down on canvas, 50 x 72 cm (19 3/4 x 28 3/8 inches). Signed and dated lower right. Du Puigaudeau landscapes available in this auction are also breathtaking. Artcurial pre-sale estimate: 20,000 – 30,000 Euros. Image copyright and courtesy Artcurial.

Ferdinand du Puigaudeau (1864-1930), “Jeune fille à la bougie,” 1891. Oil on thin cardboard laid down on canvas, 50 x 72 cm (19 3/4 x 28 3/8 inches). Signed and dated lower right. Du Puigaudeau landscapes available in this auction are also breathtaking. Artcurial pre-sale estimate: 20,000 – 30,000 Euros. Image copyright and courtesy Artcurial.

By Paul Ben-Itzak

Copyright 2016 Paul Ben-Itzak

“The opposite of war isn’t peace – it’s creation.”

–Jonathan Larsen, “RENT”

As my longtime readers know, even if Artcurial may be best known as France’s leading auction house, I venerate it as setting a curatorial example more museums would do well to follow. Not just because of its storied past as an art gallery which unabashedly announced its arrival in the mid-sixties, under the glamorous patronage of L’Oreal, in the previously hushed gallery ghetto of Paris’s 8eme arrondissement, but because of the artists I’ve been able to discover by thumbing through its auction catalogs, many of whom have been neglected by museums which have stashed their holdings away in the basement….

To access the full version of the article and more images, subscribers please e-mail paulbenitzak@gmail.com . Not a subscriber? 1-year subscriptions are just $49, or $25 for students and unemployed artists. Just designate your PayPal payment in that amount to paulbenitzak@gmail.com , or write us at that address for information on how to pay by check or in Euros or British pounds.

An Important Announcement from The Arts Voyager regarding accessing our stories and art

Starting today, all new Arts Voyager stories and art will be distributed exclusively by e-mail, to subscribers. Subscriptions are just $49/year ($25/year, students and unemployed artists), and include archive access to both the Arts Voyager and the 2,000-article Archives of The Dance Insider, our sister publication. To subscribe, designate your PayPal payment in that amount to paulbenitzak@gmail.com . Or write us to at that address to find out about other payment methods and about paying in Euros or British pounds. If you are already an Arts Voyager or Dance Insider subscriber, you are already signed up. Special Offer: Subscribe before December 15 and receive a second subscription for free — the perfect holiday gift for the Arts Voyager on your list.

Cross-Country, a Memoir of France, 20: The Man with the Child in his Eyes

“So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.” – F. Scott Fitzgerald, “The Great Gatsby”

“He’s here again: The man with the child in his eyes.” – Kate Bush

By & Copyright 2016 Paul Ben-Itzak

(Like what you’re reading? Please support the Arts Voyager by donating through PayPal, designating your payment to paulbenitzak@gmail.com, or write us at that address if you prefer to pay by check or in Euros. Based in the Dordogne and Paris, the Arts Voyager is also currently looking for lodging in Paris. Paul is also available for translating, editing, Djing, and webmastering assignments.)

In an old house in Paris, les paradises reel

“She loves books,” I insisted, struggling to get Pierre’s attention. “She’s serious. She’s got eyes to die for. She appreciates that I’m a writer.”

Briskly shelving cellophane-sealed histories of art and philosophy, squeezing dust-covered profiles of anarchist agitators and existential theorists in between musty biographies of Belle Epoch clowns and Front Populaire officials, carrying whole rows of obscure scientific revues from the balustrade overlooking the Seine lapping at the banks of the Ile St. Louis across the way — where Gauthier and Baudelaire once threw lavish hashish parties and Camille Claudel plummeted into “the years of darkness” — to his three bruised dark green metal stalls, occasionally brushing his long stringy pony-tailed graying brown hair away from his John Lennon glasses or flicking the soot off the sleeves of his Tang-colored jumpsuit, not even taking time to glance at the fathomless river rippling under the reflections of the crepuscular Sun, Pierre didn’t seem to be listening to my rapturous account of my first dinner date with Emilie, who I’d met at his 40th birthday fete near the Place Edith Piaf.

In Henry James’s “The Ambassadors,” Lambert Strether takes a break from trying to rescue a friend’s errant son from the jaws of a man-eating Parisienne to troll for literary treasures in the bookstands lining both banks of the Seine, finally scoring a complete volume of the works of Victor Hugo, poet-champion of les miserables and exiled political opponent of Napoleon III whose anguished militating against the death penalty from an island in the English Channel stretched even across the Atlantic to plead mercy for the abolitionist John Brown. If it’s true that, as pointed out by Robert Badinter – who as Mitterand’s attorney general would fulfill Hugo’s dream of decapitating the guillotine a century after his death – France is not so much the country of the Rights of Man as the country which declared the Rights of Man, it was Hugo picking up the mantle of Voltaire before passing it on to Zola who would try to ford the abyss between the declarations and the deeds. The gap between the piss-poor metier of bouquiniste – Pierre’s — and that of published author, by contrast, had frequently been bridged. Michel Ragon, the most cultivated man alive in France today (as of this writing, in late 2016), got his start as a bouquiniste before becoming the country’s premiere critic of art and architecture in the second half of the 20th century, as a side oeuvre keeping a log of proletarian movements that culminated in “La Memoir des Vaincus” (the memoir of the vanquished) the loosely fictional biography of a sort of Zelig among the anarchists or, more specifically, anarcho-syndicalists (anarchist labor organizers). (There’s a strain of anarchism in even the most encadred of French souls; as I write this, French policemen and women – the very embodiment of State order — are defying both their government and their unions by marching for more modern means and the right to shoot in self-defense.) Léo Malet – who was baptized by the anarchists and accompanied the surrealists before inventing Nestor Burma, the down-at-the-mouth French answer to Philip Marlowe, a poor man’s Maigret unafraid to dive into the muck of the Seine to catch a bad guy, whose rich vernacular and poetic vocabulary make Simenon look like Hergé and who left a trail of bodies in each of the 15 arrondissements in which his New Mysteries of Paris were set — was rewarded for this fidelity to the city with a bouquiniste’s concession, only to give it up after a few months because “I preferred reading the books to selling them.” And when another Léo, Carax – the bad boy of French cinema – wanted to demonstrate how far off the deep end the hero of his 1986 “Mauvaise Sang” had plunged after agreeing to steal a sample of HIV-contaminated blood with Juliette Binoche and Michel Piccoli, he had him break into a bouquiniste’s box after roaming the fog-addled bridges of the Seine in a midnight delirium. It was about the most fragile target one could pick; Pierre supported his metier de coeur by working part-time as a museum security guard, further trimming his expenses by jumping Metro turn styles.

So when I bought my first art book from Pierre, a tome on Impressionism published in the 1950s (the ideal epoch for the quality of the reproductions) with a portrait of Berthe Morisot as painted by her brother-in-law Manet on the cover, it was as if I had procured a part of Paris history directly from one of its guardians, another way to insert myself into the city’s lore.

Finally padlocking the last of the rusty boxes and starting off at a clipped pace for “Le chope des compagnons,” the bar across the street from his stand and the Hotel de la Ville, where he’d promised to introduce me to an Italian mason who specialized in tombstones (my dance magazine wanted to restore what at that juncture we still believed was the ballerina Taglioni’s dilapidated grave in the Montmartre cemetery, only to learn later from Edgar Allen Poe that the mother of pointe was actually buried in the Pere Lachaise sepulcher of the Bonapartiste ex-husband who’d barred her from the domicile congugale when she refused to stop dancing), Pierre scoffed, “Ecoute, it’s not you she’s interested in. She’s a little girl from the provinces set loose in Paris. For her you’re the American — you’re exotique. If it doesn’t cost you anything, pourquoi pas? Mais fait gaffe: Already she’s taking advantage of Marcel.” Marcel was the fellow bouquiniste who’d been putting Emilie up since she’d debarqued from Toulouse. “She was supposed to stay for a week-end, already she’s been there for three weeks. He has a thing for her, and she’s abusing his kindness.” As with his attempts to debunk the authenticity of Sarah Bernhardt’s ornate personal mirror, which I’d recently purchased from a Bohemian couple at a Montmartre garage sale, Pierre seemed bent on denying the legitimacy of my burgeoning French connections, be they anchored in the past or present. For me however it was clear that his skepticism derived from too many years of seeing tourists leaf through his precious books – the cellophane wrappers were meant to discourage such marauding — without buying anything, while he paid his rent watching the same Philistines photograph themselves in front of the museum masterpieces he guarded.

“She’s pretty helpless, Pierre. She needs a friend. And as for taking advantage of Marcel, it’s not her fault if she can’t find work. She’s a social worker with ado’s at a time when the government has just cut 8,000 aide jobs from the schools.”

“Okay, Candide! Fait comme tu veut. Just don’t come crying to me afterwards. The problem with you Americans is you’re too romantic about France. You think every waif you encounter wandering the quays has just stepped out of the pages of Les Miserables, is harboring the soul of Piaf, and is looking for a Marcel Cedran to protect her. And you don’t even like boxing.”

“Dans une vieux maison a Paree

Ont vecu 12 petites filles

dans deux etroite files.”

“Filles,” (sniff), “doesn’t rhyme with files,” Emilie pointed out with nasally muted contentiousness before taking a sip of chicken soup with approximated matzo balls. Unable to find Manischevitz, I’d bought a box of matzo crackers (or pain d’azyme) imported from Oran — the Algerian city on a hill in which Camus had set “The Plague,” which hosted a large Jewish colony — and pulverized them to compose the body of the balls, pulling out the major gourmet artillery to lure Emilie to my petite coin de Paradis on the rue de Paradis when she’d wanted to cancel our rendez-vous, pleading an incipient cold. “I’ll make you a big pot of hot chicken soup with matzo balls.”

“Qu’est-ce que c’est?”

“It’s like Jewish penicillin.”

“You see? It’s like I told you, your Jewish genes are trés important to you.”

“It has nothing to do with my Jewish genes,” I insisted. “It’s my California roots. My father built one of the first Nouveau California Cuisine restaurants in San Francisco, and my mother did the cooking. The only difference is her matzo balls were made of whole wheat.”

“Pourquoi pas tofu?”

“She was Old School Nouveau California Cuisine.”

“If I drink the soup, it will make me Jewish?” French humour often being more refined than American, I never knew whether Emilie was kidding.

“It won’t make you Jewish, but it might make you less blueish.” Getting no response – the “Yellow Submarine” film reference escaping her, or maybe she just didn’t get my own sense of humour – I added, “It might help your cold.”

Emilie was now perched primly on the futon with her delicate fingers clasped between her knees, looking thinner in a somber brown skirt over black tights, a light-weight tan pullover not helping her ghostly, wan pallor. In an effort to rally her spirits – the soup had only increased the sniffling, and I was having trouble charming her — I’d pulled out my Madeline omnibus. Ludwig Bemelmans’s Madeline – the hero of a series of children’s stories set in Paris which no one in France has ever heard of, just as many have never heard of “The Red Balloon” — had been the obsession of Mimi Kitagawa, my childhood best friend who’d turned over in her crib on Liberty Street in San Francisco in 1964 at the age of three and a half and breathed her last breath. During a desperate late-night passage in Greenwich Village in 1997, reeling from a push-and-pull, now I love you, now I don’t relationship with an exotic modern dancer-contortionist and meandering up Broadway in search of salvation, I’d ended up at the Strand (“8 miles of books, millions of bargains”), where a copy of the Madeline collection had beckoned to me from a display shelf near the ceiling, which I took as a hail-Mary from Mimi, by then my guardian angel. Later, whenever the ameritune of past experience threatened to blind me to present possibilities, I’d try to let Mimi become the child taking over my perspective (in Californese: “I’d channel her”), and remind myself that I had a responsibility to live my life for two.

I was now (we’re back on the rue de Paradis, in October 2004) attempting to translate the first Madeline tale into French to make it legible for Emilie, or at least get a rise out of her with my maladroit bungling.

“Filles,” Emilie was pointing out, “Is pronounced ‘fee’; files,” French for ‘lines,’ “is pronounced ‘feeel.’ So in fact, Monsieur Paul” – she looked up from the book to emphasize the point with her eyes – “they do not rhyme.” Seeing my deflated disappointment – and realizing I was doing my valiant best to distract her from the cold — she added, this time with a slight upturn to her lips and an accompanying humour in her eyes to indicate she was being ironic, “Et pour ma part, je commence a perdre le file,” the latter phrase meaning ‘lose the thread.’

“Dans deux FEEEEEEEEEEEL etroites donc, ils ont coupé leur pain,” or broke their bread, I continued, “et ont lavé leurs teeth,” which I emphasized by pointing to Bemelmans’s simple sketch of the 12 girls aligned on either side of the orphanage dinner table brushing their teeth, “avant de se mis au LITH,” I concluded, adding the lisp to “lit,” the French word for ‘bed,’ to get the rhyme with ‘teeth.’

Turning the page to a double-spread demonstrating the girls’ attitudes towards, respectively, the forces of good and those of evil, I translated “They smiled before the good” as “Devant le bon, ils se sont rejoui” to get the rhyme with my translation of “and frowned on the bad“: “Tandis que devant le mal, ils aviez que du mepris.”

“Pas mal,” Emilie admitted, finally smiling through the sniffles. “But I don’t understand why for the good he draws a picture of a rich woman feeding a carousel horse in front of les Invalides – “

“Maybe it’s Napoleon’s horse?” I offered feebly, Bonaparte’s ashes being stored at the army museum.

“And maybe you lead me to Waterloo! Et apres?”

I continued reading and translating until the page on which Madeline, after an emergency appendectomy, wakes up in a hospital room full of flowers.

Putting her thin fore-finger on one of the pictured vases, Emilie complained, “She gets all those flowers for her appendix, and you have nothing for me?”

“Au contraire! So, my belle-mere has a boutique in San Francisco where she sells exotic soaps, shampoos, bubble-baths, and body oils. It’s actually how she and my father met; her store was across the street from his restaurant.”

“Ah bon?” This had spiked her interest, as I’d cleverly maneuvered food, perfume, and romantic rendez-vous into the same sentence.

“My step-mom – er, belle-mere – actually has a French last name. So you could say I’m part French.”

She smiled, if just with her eyes.

“Anyway, I have something she sent me that I want to give you.” Even though I’d asked my step-mom to send me the wild rose body oil specifically for such an occasion, I was trying to casualize the gift so as to not scare Emilie away. Normally I’d pretend to pull such small packages out of my victim’s ear, but the last time I’d tried that trick (inherited from my grandpa in Miami Beach, a liquor salesman, who used to do it with pennies or his wide gold ring with the oval black stone), the recipient had shrieked, thinking I was plucking a bee out of her bonnet, dissipating the ambiance. So this time I merely pulled the present, enveloped in bubble-wrap, out of my pocket.

“It’s very sweet of you,” Emilie said after twisting the cap off the miniscule glass tube and taking a whiff, patting and looking down at my hand to avoid looking me in the eyes. “If you don’t mind I will save it for later, because it could make me sick if I put it on now with my cold.”

“Speaking of roses,” I said, jumping to the stereo to cue “La Vie en Rose,” “Would Mademoiselle care to dance?” Looking up noncommittally at my offered hand, which at that moment felt to me like a gorilla’s, she tentatively placed her downy palm in mine and rose with an effort. In theory, waltzing with a French girl to Piaf singing “La Vie en Rose” in my own Paris apartment on the rue de Paradis across the street from where Pissarro and Morisot learned to paint from Corot should have felt like a dream fulfilled, but my predominant sensation as I strained my back over Emilie’s doll-like hunched shoulders was the memory of dancing with Jocelyn Benford at the Lowell High School 1976 sophomore dance (“I need someone to ride the bus home with,” Jocelyn had explained, counting on my junior high crush still lingering), our ersatz silk shirts sticking sweatily together, broken up only by the ridged outline of Jocelyn’s bra, as we rotated to Earth Wind & Fire singing “Reasons.” As this French girl and I spun slowly on Paradis, the rose light-bulb I’d switched on coronating the reflection of our faces in Sarah Bernhardt’s abalone encrusted beveled mirror with a velvet aureole, Emilie felt even more fragile and fleeting in my American grizzly-bear grasp than that long ago 14-year-old.