“Le bel indifferent No. 1,” France, 2009. Digital print, 45 x 45 cm. Copyright Laurence Leblanc and courtesy Flair Gallery. The title echoes that of a radio play written by Jean Cocteau for Edith Piaf.

“Le bel indifferent No. 1,” France, 2009. Digital print, 45 x 45 cm. Copyright Laurence Leblanc and courtesy Flair Gallery. The title echoes that of a radio play written by Jean Cocteau for Edith Piaf.

by Paul Ben-Itzak

Text copyright 2018 Paul Ben-Itzak

“L’art est ni le refus total, ni le consentement à ce qui est.” (Art is neither the total refusal, nor the consent to things as they are.)

— Albert Camus, cited in the Theatre de la Ville – Sarah Bernhardt 2018-19 program

(Like what you’re reading? Please make a donation today by designating your payment via PayPal to paulbenitzak@gmail.com , or write us at that address to learn how to donate by check. No amount is too small. Looking for help feeding humans and horses, French to English translation, organizing your Web presence, DJing your event, or Communications & Art/s Consulting? Contact paulbenitzak@gmail.com .)

Based in Arles — the provençal city best known outside France as the place where Vincent Van Gogh scalded his scalp, fried his brain, and cut off his ear before being hounded out of town by irate citizens to most of whom he was not the bridge between Impressionism and Modernism but “that crazy redhead” — the Flair Gallery was founded in 2015 by Isabelle Wisniak, another redhead, whose gestalt makes her crazy like a fox. All the art programmed by Wisniak is related to animals and advancing human understanding of their kingdom. But attention: Wisniak, whose pedigree includes working for the fabled FNAC photography galleries and for temporary exhibitions at the Conciergerie (where Marie Antoinette and Danton lost their heads — both the FNAC and Conciergerie spaces are rooted in Paris archeology), is not interested in cute cat pics. The art she promotes is not just fueled by noble sentiments but solid ideas. The result is creators whose work is as aesthetically intriguing as it is politically stimulating, addressing both technical and moral questions.

For her exhibition this spring in the Church of the Friar-Preachers, organized by Wisniak, Caroline Desnoëttes erected chapels dedicated to apes (among other “graphic safaris”), a juxtaposition which might have tickled Clarence Darrow, defense attorney at the Scopes monkey trial (and, like Van Gogh, a subject of historical novelist Irving Stone) which pitted creationists against Darwinists. She also coordinated Desnoëttes’s street-perambulating expos Eléphantomatiques and Portraits d’Arlésiens hybrydes and is hosting, through today at her gallery on the picaresque rue de la Calade in the heart of the old city, Grandeur Nature, offering paintings and drawings by the Paris-based author and designer.

“I still retain the luminous memory of the large animals of Kenya, where as a teenager I was submerged by their beauty,” says Desnoëttes, who in 2014 opened a studio at the Red Cross Margency Children’s Hospital in Paris in partnership with the Louvre, the Orsay, the Rodin, and other museums. “These founding images continue to feed my work,” expressed in simple ink drawings as well as landscapes, and also encompassing a form of street art Desnoëttes dubs “éléphantômatiques.” As a child, she recalls, “I loved to follow, observe, admire, and spy on animals, and get them to come out from behind their cover, always prepared to be amazed. When they detect and perceive us, they freeze, peer out at us, consider us, size us up, and stare at us. I’d tell myself it was entirely possible that, without being aware of it, I was a member of their tribe!”

Since that keen childhood hyper-awareness of and attachment to the animal kingdom, Desnoëttes says, “I caress them with the edge of my paintbrush… pigs and goats, rats and cats. They pose like trophies whose skin is composed of ink and paper, their regards brotherly — that’s exactly what it is, what I feel since childhood: We’re brothers and we live in the same house, planet Earth.”

“Palette singe 8,” 2017. Drawing by Caroline Desnoëttes. Ink on Japanese paper, 135 x 150 cm. Copyright Thomas Julien, and courtesy Flair Gallery, Arles.

“Palette singe 8,” 2017. Drawing by Caroline Desnoëttes. Ink on Japanese paper, 135 x 150 cm. Copyright Thomas Julien, and courtesy Flair Gallery, Arles.

It’s this tribal bond that strikes me in Desnoëttes’s 2017 ink drawing “Palette singe 8,” in which the ape echoes the simian-human connection traced by Eugene O’Neill in “The Hairy Ape,” only in reverse, the pensive monkey’s expression seeming human; you want to ask him what he’s pondering. “Full moon panther 4,” also created last year, reminds me both of the panther that used to pace poignantly back and forth, like its polar bear brother neighbor, in the confines of a 20-foot long cell in the San Francisco Zoo (where the apes were more inclined to interact with the public, throwing their caca at anyone who got too close to their perch on “Monkey Island”), quietly going mad, and its relative in Jacques Tourneur’s 1942 “Cat People,” where feline empathy was also stirred up by the purring Simone Simon (Eartha Kitt had nothing on her), into whom the panther metamorphosed when the Sun came up.

“Panthère pleine lune 4,” 2017. Drawing by Caroline Desnoëttes. Ink on Indian paper, 90 cm. Copyright Thomas Julien and courtesy Flair Gallery.

“Panthère pleine lune 4,” 2017. Drawing by Caroline Desnoëttes. Ink on Indian paper, 90 cm. Copyright Thomas Julien and courtesy Flair Gallery.

The presence of an art gallery sensible to animals in this particular geography is not anodyne. When I mentioned to a friend that I was thinking of moving to Arles (because of the literary and art scenes, as well as the proximity to the Camargue and potential horse work), he praised its Bohemian ambiance and artistic nature, but said he was distressed by the area’s “Tauromaché.” Having spent several years living in semi-rural villages in the south of France, my own view on humans who kill animals has evolved. From their daily proximity with nature, my hunter friends have a grand respect for and understanding of animals. But even if they are distinguished from bull-fighters in eating everything they kill — thus an argument of utility can be made — hunters like matadors are engaged in sporting matches in which their opponents are involuntary participants. (Though it might be argued that at least bull-fighters risk own their lives.) It’s the humans who have determined the rules of engagement and manipulated the balance of power. Its defenders argue that bull-fighting, or Tauromaché, is also an art. With a view towards supporting this thesis, I broke out a collection of Editions David postcard reproductions I have of Picasso’s aqua-tint illustrations of the famous Pepe Illo bull-fighting scenes. Published in 1957 in Barcelona by Gustavo Gili for its “La Cometa” editions, Picasso executed them after attending the bull-fights in the Roman arena of… Arles.

Several of the tableaux indicate how ridiculous the contest is with its inflated pomp: The matador parading into the arena with his coterie of marching and mounted attendants, primping like a bride, or being applauded after having vanquished the bull in a match that was ultimately rigged because the humans set the rules. Others, however, depict the respect in which the beast is held: The matador kneeling before the bovine, spreading his cape out on the ground between them as if in tribute, or saluting an animal opponent proudly clenching a morsel of torn cape between his teeth. Another shows the opponents facing off on visually equal terms, at least as far as the arena goes: The bull standing in attendance, the matador seated and gently waving his cape towards the animal as, in the foreground, another matador and an elegant woman in a lavish hat watch from the rungs. I’m less sure about the elegance of another which shows the audience and matadors in the shadows, the bull standing under blazing floodlights; is he the honored star or the spectacle, like the Kroebers’ Ishi in Berkeley? But my favorite is a village-scape which depicts the townspeople mounting, by foot, burro, truck and cart the gentle hills in the foreground to the Arles arena in the background. It’s an occasion. It’s a culture. You can say it’s not a civilized culture because it’s not your culture and you weren’t raised in it, but is it really so barbaric as all that? Another tableau — and perhaps the one the Taurus in me, who takes Ferdinand as his model, identifies with the most — pictures the bulls reposing in the countryside, monitored by a single guardian (albeit one armed with a spear).

In Texas, we don’t kill our bulls, we just taunt them until they’re mad enough to charge. When I caught the Rodeo & Stockyard show in Fort Worth — the largest and oldest indoor rodeo in the world – in 2012, a bull twice the size of the cobalt ones who gambol among the marshes of the Camargue, to which Arles is the gateway, nearly succeeded in hurtling the barrier which separated his pen from the stands and mounting in the press seats. (If you want to tame the media jackals, put them next to the bull pen.) He was finally lured into the arena by the clown, the most courageous human player in the rodeo, with only a thin barrel protecting him from the horns.

Before a gig working as ranch chef and stable boy on a Texas pony farm later that same year, my closest exposure to horses — my equine fix — came from strolling through the large hangar at the stockyard show, where I found the aroma of horse-dung as intoxicating as some in the South of France find prune eau de vie.

The stockyards in the Will Rogers Center neighboring several museums in the city’s “Cultural District,” during a break between cowboy (and girl) poetry jam sessions and after checking out a quilting exhibition at the Cowgirl Hall of Fame, I moseyed over to the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, curious to see if there was any overlap — if the real cowboys from the stockyard show and rodeo were checking out Romance Maker: The Watercolors of Charles M. Russell, an exhibition devoted to the late 19th, early 20th century artist who, along with his contemporary Frederick Remington, was largely responsible for the image Hollywood and thus America and the world would subsequently cultivate of the cowboy and his equine auxiliary. On the suggestion of his cowboy-philosopher friend Rogers (“No one ever went broke under-estimating the intelligence of the American public”) that it was a good investment, Carter, publisher of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, bought a pair of Russell paintings which grew into the collection that became the basis of the museum he later financed. The Carter is free 24/7 at the behest of its founder, who wanted future generations of children to have access to the art he didn’t growing up. (The Metropolitan Museum in New York, which recently abandoned its pay-as-you-can admission, except for locals, could stand to learn a lesson.)

After paying my respects to Ben Shahn’s “Comics,” a towering painting on the mezzanine level portraying a boy reading the funny pages before a vast wall, I ambled into the Russell exhibition and sidled over to where an older cowboy, a slightly younger cowboy, and an eternally young cowgirl whose long grey-black hair fell in two braided tresses over her plaid shirt and blue jeans had paused in front of “The Challenge No. 2,” a tableau from 1898 in which two wild horses are pitched in battle. With my dark-brown garage-sale cowboy work-boots, snap-button silver shirt, red bandana (came with the boots), black Dickies jeans, broad-brimmed straw cowboy hat with the longhorn emblazoned on its flaming orange band and, facsimilating the jingle of spurs, the collars of my three dead cats dangling from my wrist, I hoped to be able to pass.

Charles Marion Russell, “The Challenge No. 2,” 1898. Watercolor. Bob and Betsy Magness Collection, Denver Art Museum, 52.2005. From the exhibition Romance Maker: The Watercolors of Charles M. Russell, which showed at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art and at the C.M. Russell Museum in Great Falls, Montana in 2012, as earlier published on the Dance Insider & Arts Voyager.

Charles Marion Russell, “The Challenge No. 2,” 1898. Watercolor. Bob and Betsy Magness Collection, Denver Art Museum, 52.2005. From the exhibition Romance Maker: The Watercolors of Charles M. Russell, which showed at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art and at the C.M. Russell Museum in Great Falls, Montana in 2012, as earlier published on the Dance Insider & Arts Voyager.

“Isn’t that something?” the younger cowboy was exclaiming, indicating the sparring horses. The older man, who like his friend wore glasses under his broad grey Stetson, was jolted into a memory. “When I lost the ranch during the draught in the 1990s, I started hiring out breakin’ broncs. Now Bob, who was my neighbor, asked me to come over there and break a half a dozen of them in. After I was all done and he asked me ‘How much?,’ I told ‘im I wasn’t gonna charge ‘im…. But there was one horse there that was unlike any I’d ever seen before, and I told ‘im I wouldn’t mind having that one. He was real muscled up top. You know these young cowboys, they flatten ’em out on the back by cross-breeding them, just because everybody does it.” I lost some of the conversation, and picked it back up at, “He called me yesterday and invited me up next week. I’d invite you but it’s not the kind of thing to bring guests to.” Apparently, ‘Bob’ was preparing to shoot several horses who were old or terminally ill, and was giving his friend a chance to pick up the horse he’d hankered after earlier. “Better than turning it over to the soap factory!” “Sounds like he’s real old school!” said the other cowboy. “I didn’t know they shot ’em any more. I guess he just wants to save money on the Vet!”

The two cowboys and the cowgirl wife moved on to “The Chaperone / Waiting,” an 1897 watercolor of a brave on a horse and a maiden fetching water or cleaning clothes in a pond, with an elderly squaw standing between them. “Now, this is just incredible,” said the second cowboy, sweeping his palm over the receding landscape. (Because of his rustic subject, Russell’s is sometimes relegated to a second, lesser tier of artistic achievement, but make no mistake: Like Remington’s, his technique — the means he used to accomplish his romantic effects — was elaborate and calculated.) Then the man’s wife laughed, pointing to the chaperone. “Reminds me of our first date, at the drive-in. My grandmother came and insisted on sitting between us.”

This is what art at its best does; it distills life, using technique to reflect it back to the observer in a way that doesn’t just evoke physical recognition but resonates and stimulates not only intellectually, but emotionally, sensually, and spiritually.

(When I was running a gallery in a small village on the banks of the Nile in the Languedoc region of France, the window display that finally made local passersby stop and look was not the modern paintings, nor my curio shop knick-knacks, nor even my clever hand-drawn comics, but a gargantuan bird’s nest an American neighbor had discovered in the woods.)

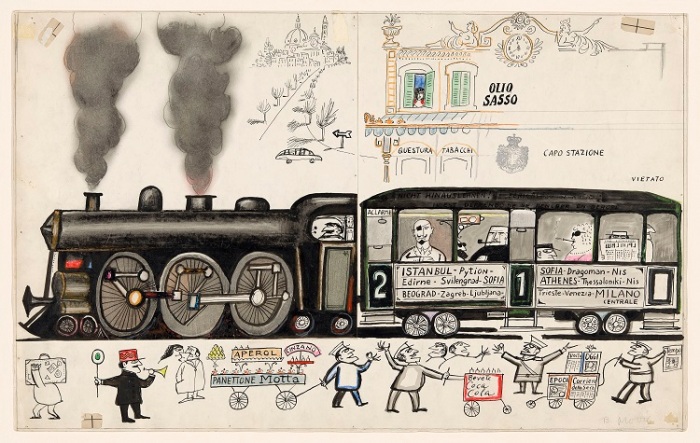

When the rodeo wasn’t in town, I’d get my horse fix at the quarter-horse competitions, which show-cased the equines’ ability to herd. So when, picking up Boris Vian’s play “L’equarrissage pour tous” recently, I looked up ‘equarrissage’ and found it translated as “the quartering of horses,” I was confused until French friends explained to me that here the quartering in question is not activated by the horses on straying heifers but imposed on them, post-mortem. (The equarrisseur not to be confused with the chevillard, who hacks horses up for meat.) Vian’s play takes place June 6, 1944, in the Normandy village of Arromanches (where the allies landed 1 million men and set up temporary concrete unloading docks, the remnants of which still peer out of the surf today), chez an equarrisseur more concerned with marrying off his daughter to the German soldier she’s been sleeping with for four years than the bombs rattling the house every few minutes and the steady traffic through his home of American soldiers, German soldiers, an errant daughter who parachutes into the living room with the Russian army and a prodigal son who lands in American military garb. (There’s also an American ordinance officer who, just in time for the wedding, delivers three boxes containing a ready-to-assemble priest, religion joining chocolate and tobacco among the essential provisions furnished by the Allies.) Inconvenient visitors inevitably get bopped on the head and dropped into the pit otherwise reserved for the decomposing horse parts, whose putrid odor is no doubt the reason two French officers finally arrive to announce that the house doesn’t fit in with reconstruction plans, terminating the play by blowing it up with its owner before he can realize the profits the invasion and the accompanying horse carnage no doubt promise, horses (probably Normandy Percherons, known for not being easily rattled by mud or canons) being a vital accessory to and thus recurrent casualty of war. (Vian described his drama as an “anarchist burlesque.” Essentially, he’s saying: Even a good war stinks. My idea is to produce the play on June 6, 2019, in Arromanches, for the 75th anniversary of the Debarquement. Perhaps with marionettes, who might be more resistant than humans to the abuse Vian imposes on his personages to make his point.)

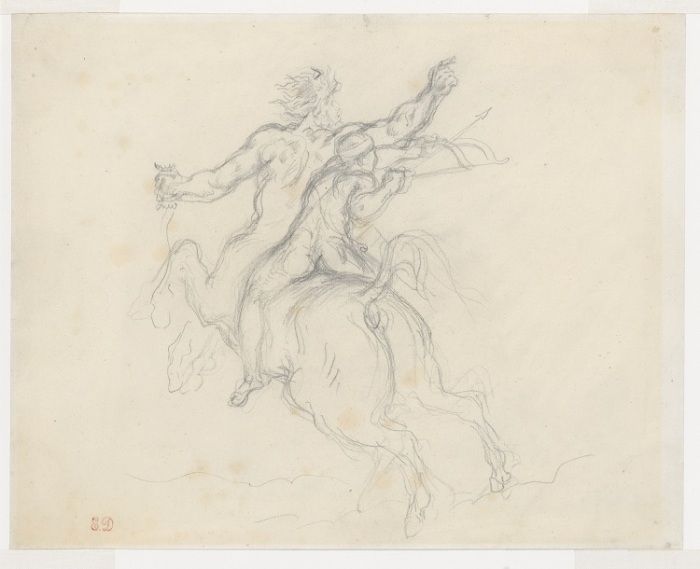

The horse’s historic martial role, as the only thing holding up Achilles, is captured in Devotion to Drawing: The Karen B. Cohen Collection of Eugène Delacroix, opening at the Metropolitan Museum of Art July 17, in this drawing:

Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798–1863), “The Education of Achilles,” ca. 1844. Graphite, 9 5/16 x 11 11/16 inches (23.6 x 29.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift from the Karen B. Cohen Collection of Eugène Delacroix, in honor of Emily Rafferty, 2014 (2014.732.3).

Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798–1863), “The Education of Achilles,” ca. 1844. Graphite, 9 5/16 x 11 11/16 inches (23.6 x 29.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift from the Karen B. Cohen Collection of Eugène Delacroix, in honor of Emily Rafferty, 2014 (2014.732.3).

Like Vian’s play and the Normandy invasion, Laurence Leblanc, whose photography Isabelle Wisniak (remember her?) exhibits June 30 through September 12, also began on June 6, being born on that day in 1967. The photographs on view in Leblanc’s Flair show — at least those which intrigue me the most among what I’ve seen — were taken 40 years earlier in Kentucky (the horses presumably associated with the derby). After discovering them in a dusty album in a rear room at the municipal library of Deauville (Normandy again), Leblanc decided to adjust the original images in a way that re-calibrated the power rapport between horse and man to one of more equilibrium. Take a look at this shot, tweaked by Leblanc:

“Famous Mare 1,” France, 2016. Copyright Laurence Leblanc and courtesy Flair Gallery.

“Famous Mare 1,” France, 2016. Copyright Laurence Leblanc and courtesy Flair Gallery.

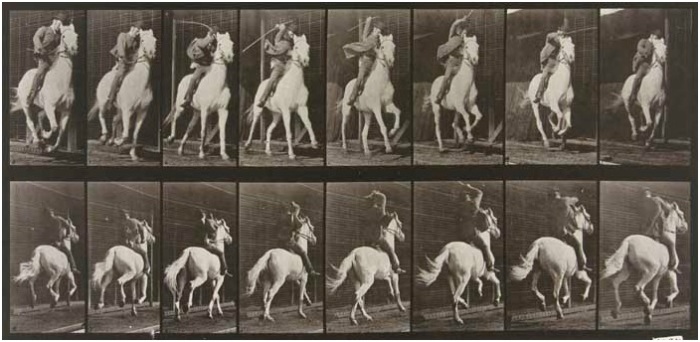

… And then at this one by 19th-century photographic pioneer Eadweard Muybridge, known for his staged photos:

From the exhibition “The Medium and Its Metaphors,” first covered by the AV in 2012: Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904),”Dan with Rider (.064 Second), One Stride in 8 Phases (Left Lead),” ca. 1887. Collotype. Amon Carter Museum of American Art P1970.56.13.

From the exhibition “The Medium and Its Metaphors,” first covered by the AV in 2012: Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904),”Dan with Rider (.064 Second), One Stride in 8 Phases (Left Lead),” ca. 1887. Collotype. Amon Carter Museum of American Art P1970.56.13.

At first glance, the Leblanc made me think of the Muybridge. On closer examination, I realized that in the Muybridge, the rider is beating the horse; in Leblanc’s tweaking of the 1927 photo, the horse is staring down the stable boy (on whom Leblanc seems to have performed a digital equarissage operation), challenging the master-subjugated relationship.

I can’t over-state the global resonances this image by Leblanc, nor another, “Famous Mares No. 3,” suggested to me, nor the personal catharsis they delivered.

What started me on the trail to Wisniak’s gallery was discovering yet another major arts institution whose otherwise noble mission has been compromised, in my view, by the profile of one of its main supporters. In the U.S., this has been most infamously manifest by institutions like New York City Ballet and the Metropolitan Museum accepting large donations from the Koch Brothers (funders of phony science debunking global warming and anti-Labor politicians, among other nefest causes) and, in the case of the Met, the Sackler family (owners of Perdue Pharma, linked to the opiate crisis plaguing the United States, and who have lent their name to the Met wing housing the Temple of Dendur). Instead of getting up on my high horse again and ranting the institution in question, this time I thought I’d try to scout out arts institutions who, in lieu of accepting and parlaying with the world as it is, agitate for the world as it ought to be. By focusing on art related to animals — *and* in a place like Arles with its embedded Tauromaché culture — Wisniak is militating for the cause of animals in the largest sense, getting us on their side by enabling what artists do best: Teach empathy.

On a personal level, contemplating Leblanc’s photos re-imagining the rapport between the horse and the stable boy stirred a memory like those of the Texas cowboys before the Russell watercolor – and, like the protagonist of Herman Hesse’s “Journey to the East,” started me on the road to seeing an episode of my past in a new, more positive light.

Chris, the New Zealand rodeo champion on the Texas pony farm where I fed the humans and helped feed the horses, came from a domain, rodeo, where the goal is not just to master the horse but to show off that mastery. When I met him he was a firm believer in and practitioner of the natural method, which relies more on coaxing, cajoling, and habituating the horses than making them submit with whips and spurs. Neither Chris nor PJ, his deputy, also from New Zealand, wore spurs. (Nor cowboy boots. Nor — demonstrating their confidence that the horses wouldn’t toss them — chaps. Chris preferred holey jeans.) “If you have to wear spurs, you haven’t done your job right,” Chris explained. PJ wasn’t above cursing at the horses if they strayed or dawdled during morning turn-out (the ranch also boarded mares), but he also scolded me (correctly) when I was impatient with the animals, either being too quick to raise my voice when a filly tried to escape her stall in the “mare hotel” I was responsible for watering and cleaning by myself at noontime (a palomino named Cookie was particularly rambunctious) when I entered to scoop the poop, or not pausing long enough between stages when using the graduated scale of coaxing he recommended when I was trying to get the horse to back up while I opened the door of her stall: Start in a whisper, and only increase your tone if the horse doesn’t heed you. “You have to give the horse time to reflect and process what you’re telling her,” he said, in a variation of “You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make him drink it,” the horse in question obviously not being from sage-brush-dry Texas. “If you just keep insisting without pausing to let her absorb what you’ve just said, she gets confused.” It’s a lesson I’ve tried to remember to apply to human relationships, not always with success. (Nor with horses, as the Percheron I tried to lead around the vines – these days, this breed is more likely to be used for farm labor than cat food — during the harvest at a natural winery near Cahors in 2014 will confirm.)

When I insisted PJ watch an episode of Bonanza with me in the bunkhouse we shared, what struck him most was the ponds. “We don’t have those in New Zealand.” PJ loved horses so much that for the six months he was obliged to remain in New Zealand, he worked as a horse truck driver just so he could be near them. One morning I asked PJ how he was doing. “Any day when I wake up to discover I didn’t die in my sleep is a good one.” My own proudest moments came when I was put in charge of feeding a trio including “the blind mare” in a pasture closer to our bunkhouse than the main house, which meant I got to ride the golf-cart out there, usually in the company of several canine passengers who jumped in as soon as I got rolling.

Besides planning and preparing hot meals for lunch and dinner, I also helped PJ with the afternoon feed and stall-cleaning, and eventually took charge of the noon watering and poop-scooping to give PJ more time with Chris, who I was able to watch work with the horses as my other duties allowed. When I made my first dish, a simple quiche, Chris took one bite and proclaimed, “If he can cook like this, I don’t care what he does with the horses.” (I soon earned a reputation in the area as “the French chef,” and if you think this digression is also my way of seeking more work feeding horses and humans, you’re right. The horse-feeding was more complex than you might think. Chris’s wife and collaborator, whom I’ll call Cheryl to protect her privacy and who also taught me a lot, had worked out complex and individualized mixtures of nutrients for each resident of the mare hotel.)

As they enter a Sierra mining camp in Sam Peckinpah’s 1962 “Ride the High Country,” the horses are all that’s keeping Mariette Hartley, Ron Starr, Joel McCrea, and Randolph Scott from looking like what they are: Two greenhorns and two over-the-hill cowpokes. Image courtesy Cinematheque de Toulouse.

As they enter a Sierra mining camp in Sam Peckinpah’s 1962 “Ride the High Country,” the horses are all that’s keeping Mariette Hartley, Ron Starr, Joel McCrea, and Randolph Scott from looking like what they are: Two greenhorns and two over-the-hill cowpokes. Image courtesy Cinematheque de Toulouse.

One late afternoon after I’d finished helping PJ with the feed and stable cleaning and prepared the galette batter for the evening human feed, crossing the pastures that separated the main house from the one I shared with PJ, I decided to take a detour and enjoy my ‘knock-off’ beer (in French, “aperitif”) on a dilapidated couch PJ had installed in the midst of an overgrown field where a baker’s dozen of horses were left to roam. Sinking into the sofa in a position that proscribed a quick exit, I looked up to see 14 very immense horses standing 25 feet away slowly turn their gaze towards me; or as Desnoëttes might put it, “debusquing” me. I can’t say the episode totally evacuated the fear of horses that accompanies my attirance to them. (Much as I’d like to, the human horse hero I identify with the most is not Joel McCrea, but 12-year-old Scarlett Johannsen in “The Horse Whisperer,” alternately drawn to and terrified of the animals after a pal gets fatally tossed by a panicked mount.) But it was the most bare moment I’ve ever had with horses, and one of the most bare moments I’ve ever experienced in my life, just a moment of being: with the animal, with my intimidation in his presence, with advancing to the limit of my fears, as modest as that front may seem in comparison with the dreads that torment others, including my own cowboy heroes; this was my ravine, not navigating its precipitating edges on my pony, but simply approaching them and accepting what that felt like. To share, even if only for a moment, the universe of these belles indifferentes.

I thank Laurence Leblanc — and her gallerist — for helping me revive that moment… and for a catharsis — for isn’t that another vital role of art? — that frees me to dream of feeding horses and humans again, perhaps in a milieu like this one:

PBI’s next destination?: Horses and water in the Camargue, outside Arles.

PBI’s next destination?: Horses and water in the Camargue, outside Arles.

“Famous Mares 3 ,” France, 2016. Copyright Laurence Leblanc and courtesy Flair Gallery.

Paul Ben-Itzak’s new 40-page Memoir, including art by Ansel Adams, Robert L. Berry, Lou Chapman, James Daugherty, Gustave Caillebotte, Jacob Lawrence, Sylvie Lesgourgues, David Levinthal, Roy Lichtenstein, Sam Peckinpah, Charles M. Russell, Saul Steinberg, and Frank Lloyd Wright from both current exhibitions and the AV Archives, is now available. To receive your own copy as a PDF or Word document, including 35 illustrations, please send $19.95 to the AV by designating your PayPal payment to paulbenitzak@gmail.com, or write us at that address to learn about payment by check. Your purchase includes a complimentary one-year subscription to the Arts Voyager and

Paul Ben-Itzak’s new 40-page Memoir, including art by Ansel Adams, Robert L. Berry, Lou Chapman, James Daugherty, Gustave Caillebotte, Jacob Lawrence, Sylvie Lesgourgues, David Levinthal, Roy Lichtenstein, Sam Peckinpah, Charles M. Russell, Saul Steinberg, and Frank Lloyd Wright from both current exhibitions and the AV Archives, is now available. To receive your own copy as a PDF or Word document, including 35 illustrations, please send $19.95 to the AV by designating your PayPal payment to paulbenitzak@gmail.com, or write us at that address to learn about payment by check. Your purchase includes a complimentary one-year subscription to the Arts Voyager and