For the Arts Voyager’s full illustrated commentary on the Rencontres de la Photographie held last summer in Arles, France, subscribers please contact paulbenitzak@gmail.com. Not yet a subscriber? Subscribe today for just $36/year by designating your PayPal payment to paulbenitzak@gmail.com, or write us at that address to learn how to pay by check. Above, from the Arles exhibition The Train: RFK’s Last Journey: Paul Fusco/Magnum Photos, Untitled, from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968. The exhibition is part of a mini-festival within the festival, America Great Again, also featuring work from Robert Frank, Raymond Depardon, and others. Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles 50 years ago this month, at the apex of the Democratic presidential primaries. Courtesy of the Danziger Gallery.

For the Arts Voyager’s full illustrated commentary on the Rencontres de la Photographie held last summer in Arles, France, subscribers please contact paulbenitzak@gmail.com. Not yet a subscriber? Subscribe today for just $36/year by designating your PayPal payment to paulbenitzak@gmail.com, or write us at that address to learn how to pay by check. Above, from the Arles exhibition The Train: RFK’s Last Journey: Paul Fusco/Magnum Photos, Untitled, from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968. The exhibition is part of a mini-festival within the festival, America Great Again, also featuring work from Robert Frank, Raymond Depardon, and others. Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles 50 years ago this month, at the apex of the Democratic presidential primaries. Courtesy of the Danziger Gallery.

Category Archives: Subscribe to the Arts Voyager

Horse Sense: Ambiance animal art in Arles, Normandy, NY, the Sierras, & Texas

“Le bel indifferent No. 1,” France, 2009. Digital print, 45 x 45 cm. Copyright Laurence Leblanc and courtesy Flair Gallery. The title echoes that of a radio play written by Jean Cocteau for Edith Piaf.

“Le bel indifferent No. 1,” France, 2009. Digital print, 45 x 45 cm. Copyright Laurence Leblanc and courtesy Flair Gallery. The title echoes that of a radio play written by Jean Cocteau for Edith Piaf.

by Paul Ben-Itzak

Text copyright 2018 Paul Ben-Itzak

“L’art est ni le refus total, ni le consentement à ce qui est.” (Art is neither the total refusal, nor the consent to things as they are.)

— Albert Camus, cited in the Theatre de la Ville – Sarah Bernhardt 2018-19 program

(Like what you’re reading? Please make a donation today by designating your payment via PayPal to paulbenitzak@gmail.com , or write us at that address to learn how to donate by check. No amount is too small. Looking for help feeding humans and horses, French to English translation, organizing your Web presence, DJing your event, or Communications & Art/s Consulting? Contact paulbenitzak@gmail.com .)

Based in Arles — the provençal city best known outside France as the place where Vincent Van Gogh scalded his scalp, fried his brain, and cut off his ear before being hounded out of town by irate citizens to most of whom he was not the bridge between Impressionism and Modernism but “that crazy redhead” — the Flair Gallery was founded in 2015 by Isabelle Wisniak, another redhead, whose gestalt makes her crazy like a fox. All the art programmed by Wisniak is related to animals and advancing human understanding of their kingdom. But attention: Wisniak, whose pedigree includes working for the fabled FNAC photography galleries and for temporary exhibitions at the Conciergerie (where Marie Antoinette and Danton lost their heads — both the FNAC and Conciergerie spaces are rooted in Paris archeology), is not interested in cute cat pics. The art she promotes is not just fueled by noble sentiments but solid ideas. The result is creators whose work is as aesthetically intriguing as it is politically stimulating, addressing both technical and moral questions.

For her exhibition this spring in the Church of the Friar-Preachers, organized by Wisniak, Caroline Desnoëttes erected chapels dedicated to apes (among other “graphic safaris”), a juxtaposition which might have tickled Clarence Darrow, defense attorney at the Scopes monkey trial (and, like Van Gogh, a subject of historical novelist Irving Stone) which pitted creationists against Darwinists. She also coordinated Desnoëttes’s street-perambulating expos Eléphantomatiques and Portraits d’Arlésiens hybrydes and is hosting, through today at her gallery on the picaresque rue de la Calade in the heart of the old city, Grandeur Nature, offering paintings and drawings by the Paris-based author and designer.

“I still retain the luminous memory of the large animals of Kenya, where as a teenager I was submerged by their beauty,” says Desnoëttes, who in 2014 opened a studio at the Red Cross Margency Children’s Hospital in Paris in partnership with the Louvre, the Orsay, the Rodin, and other museums. “These founding images continue to feed my work,” expressed in simple ink drawings as well as landscapes, and also encompassing a form of street art Desnoëttes dubs “éléphantômatiques.” As a child, she recalls, “I loved to follow, observe, admire, and spy on animals, and get them to come out from behind their cover, always prepared to be amazed. When they detect and perceive us, they freeze, peer out at us, consider us, size us up, and stare at us. I’d tell myself it was entirely possible that, without being aware of it, I was a member of their tribe!”

Since that keen childhood hyper-awareness of and attachment to the animal kingdom, Desnoëttes says, “I caress them with the edge of my paintbrush… pigs and goats, rats and cats. They pose like trophies whose skin is composed of ink and paper, their regards brotherly — that’s exactly what it is, what I feel since childhood: We’re brothers and we live in the same house, planet Earth.”

“Palette singe 8,” 2017. Drawing by Caroline Desnoëttes. Ink on Japanese paper, 135 x 150 cm. Copyright Thomas Julien, and courtesy Flair Gallery, Arles.

“Palette singe 8,” 2017. Drawing by Caroline Desnoëttes. Ink on Japanese paper, 135 x 150 cm. Copyright Thomas Julien, and courtesy Flair Gallery, Arles.

It’s this tribal bond that strikes me in Desnoëttes’s 2017 ink drawing “Palette singe 8,” in which the ape echoes the simian-human connection traced by Eugene O’Neill in “The Hairy Ape,” only in reverse, the pensive monkey’s expression seeming human; you want to ask him what he’s pondering. “Full moon panther 4,” also created last year, reminds me both of the panther that used to pace poignantly back and forth, like its polar bear brother neighbor, in the confines of a 20-foot long cell in the San Francisco Zoo (where the apes were more inclined to interact with the public, throwing their caca at anyone who got too close to their perch on “Monkey Island”), quietly going mad, and its relative in Jacques Tourneur’s 1942 “Cat People,” where feline empathy was also stirred up by the purring Simone Simon (Eartha Kitt had nothing on her), into whom the panther metamorphosed when the Sun came up.

“Panthère pleine lune 4,” 2017. Drawing by Caroline Desnoëttes. Ink on Indian paper, 90 cm. Copyright Thomas Julien and courtesy Flair Gallery.

“Panthère pleine lune 4,” 2017. Drawing by Caroline Desnoëttes. Ink on Indian paper, 90 cm. Copyright Thomas Julien and courtesy Flair Gallery.

The presence of an art gallery sensible to animals in this particular geography is not anodyne. When I mentioned to a friend that I was thinking of moving to Arles (because of the literary and art scenes, as well as the proximity to the Camargue and potential horse work), he praised its Bohemian ambiance and artistic nature, but said he was distressed by the area’s “Tauromaché.” Having spent several years living in semi-rural villages in the south of France, my own view on humans who kill animals has evolved. From their daily proximity with nature, my hunter friends have a grand respect for and understanding of animals. But even if they are distinguished from bull-fighters in eating everything they kill — thus an argument of utility can be made — hunters like matadors are engaged in sporting matches in which their opponents are involuntary participants. (Though it might be argued that at least bull-fighters risk own their lives.) It’s the humans who have determined the rules of engagement and manipulated the balance of power. Its defenders argue that bull-fighting, or Tauromaché, is also an art. With a view towards supporting this thesis, I broke out a collection of Editions David postcard reproductions I have of Picasso’s aqua-tint illustrations of the famous Pepe Illo bull-fighting scenes. Published in 1957 in Barcelona by Gustavo Gili for its “La Cometa” editions, Picasso executed them after attending the bull-fights in the Roman arena of… Arles.

Several of the tableaux indicate how ridiculous the contest is with its inflated pomp: The matador parading into the arena with his coterie of marching and mounted attendants, primping like a bride, or being applauded after having vanquished the bull in a match that was ultimately rigged because the humans set the rules. Others, however, depict the respect in which the beast is held: The matador kneeling before the bovine, spreading his cape out on the ground between them as if in tribute, or saluting an animal opponent proudly clenching a morsel of torn cape between his teeth. Another shows the opponents facing off on visually equal terms, at least as far as the arena goes: The bull standing in attendance, the matador seated and gently waving his cape towards the animal as, in the foreground, another matador and an elegant woman in a lavish hat watch from the rungs. I’m less sure about the elegance of another which shows the audience and matadors in the shadows, the bull standing under blazing floodlights; is he the honored star or the spectacle, like the Kroebers’ Ishi in Berkeley? But my favorite is a village-scape which depicts the townspeople mounting, by foot, burro, truck and cart the gentle hills in the foreground to the Arles arena in the background. It’s an occasion. It’s a culture. You can say it’s not a civilized culture because it’s not your culture and you weren’t raised in it, but is it really so barbaric as all that? Another tableau — and perhaps the one the Taurus in me, who takes Ferdinand as his model, identifies with the most — pictures the bulls reposing in the countryside, monitored by a single guardian (albeit one armed with a spear).

In Texas, we don’t kill our bulls, we just taunt them until they’re mad enough to charge. When I caught the Rodeo & Stockyard show in Fort Worth — the largest and oldest indoor rodeo in the world – in 2012, a bull twice the size of the cobalt ones who gambol among the marshes of the Camargue, to which Arles is the gateway, nearly succeeded in hurtling the barrier which separated his pen from the stands and mounting in the press seats. (If you want to tame the media jackals, put them next to the bull pen.) He was finally lured into the arena by the clown, the most courageous human player in the rodeo, with only a thin barrel protecting him from the horns.

Before a gig working as ranch chef and stable boy on a Texas pony farm later that same year, my closest exposure to horses — my equine fix — came from strolling through the large hangar at the stockyard show, where I found the aroma of horse-dung as intoxicating as some in the South of France find prune eau de vie.

The stockyards in the Will Rogers Center neighboring several museums in the city’s “Cultural District,” during a break between cowboy (and girl) poetry jam sessions and after checking out a quilting exhibition at the Cowgirl Hall of Fame, I moseyed over to the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, curious to see if there was any overlap — if the real cowboys from the stockyard show and rodeo were checking out Romance Maker: The Watercolors of Charles M. Russell, an exhibition devoted to the late 19th, early 20th century artist who, along with his contemporary Frederick Remington, was largely responsible for the image Hollywood and thus America and the world would subsequently cultivate of the cowboy and his equine auxiliary. On the suggestion of his cowboy-philosopher friend Rogers (“No one ever went broke under-estimating the intelligence of the American public”) that it was a good investment, Carter, publisher of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, bought a pair of Russell paintings which grew into the collection that became the basis of the museum he later financed. The Carter is free 24/7 at the behest of its founder, who wanted future generations of children to have access to the art he didn’t growing up. (The Metropolitan Museum in New York, which recently abandoned its pay-as-you-can admission, except for locals, could stand to learn a lesson.)

After paying my respects to Ben Shahn’s “Comics,” a towering painting on the mezzanine level portraying a boy reading the funny pages before a vast wall, I ambled into the Russell exhibition and sidled over to where an older cowboy, a slightly younger cowboy, and an eternally young cowgirl whose long grey-black hair fell in two braided tresses over her plaid shirt and blue jeans had paused in front of “The Challenge No. 2,” a tableau from 1898 in which two wild horses are pitched in battle. With my dark-brown garage-sale cowboy work-boots, snap-button silver shirt, red bandana (came with the boots), black Dickies jeans, broad-brimmed straw cowboy hat with the longhorn emblazoned on its flaming orange band and, facsimilating the jingle of spurs, the collars of my three dead cats dangling from my wrist, I hoped to be able to pass.

Charles Marion Russell, “The Challenge No. 2,” 1898. Watercolor. Bob and Betsy Magness Collection, Denver Art Museum, 52.2005. From the exhibition Romance Maker: The Watercolors of Charles M. Russell, which showed at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art and at the C.M. Russell Museum in Great Falls, Montana in 2012, as earlier published on the Dance Insider & Arts Voyager.

Charles Marion Russell, “The Challenge No. 2,” 1898. Watercolor. Bob and Betsy Magness Collection, Denver Art Museum, 52.2005. From the exhibition Romance Maker: The Watercolors of Charles M. Russell, which showed at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art and at the C.M. Russell Museum in Great Falls, Montana in 2012, as earlier published on the Dance Insider & Arts Voyager.

“Isn’t that something?” the younger cowboy was exclaiming, indicating the sparring horses. The older man, who like his friend wore glasses under his broad grey Stetson, was jolted into a memory. “When I lost the ranch during the draught in the 1990s, I started hiring out breakin’ broncs. Now Bob, who was my neighbor, asked me to come over there and break a half a dozen of them in. After I was all done and he asked me ‘How much?,’ I told ‘im I wasn’t gonna charge ‘im…. But there was one horse there that was unlike any I’d ever seen before, and I told ‘im I wouldn’t mind having that one. He was real muscled up top. You know these young cowboys, they flatten ’em out on the back by cross-breeding them, just because everybody does it.” I lost some of the conversation, and picked it back up at, “He called me yesterday and invited me up next week. I’d invite you but it’s not the kind of thing to bring guests to.” Apparently, ‘Bob’ was preparing to shoot several horses who were old or terminally ill, and was giving his friend a chance to pick up the horse he’d hankered after earlier. “Better than turning it over to the soap factory!” “Sounds like he’s real old school!” said the other cowboy. “I didn’t know they shot ’em any more. I guess he just wants to save money on the Vet!”

The two cowboys and the cowgirl wife moved on to “The Chaperone / Waiting,” an 1897 watercolor of a brave on a horse and a maiden fetching water or cleaning clothes in a pond, with an elderly squaw standing between them. “Now, this is just incredible,” said the second cowboy, sweeping his palm over the receding landscape. (Because of his rustic subject, Russell’s is sometimes relegated to a second, lesser tier of artistic achievement, but make no mistake: Like Remington’s, his technique — the means he used to accomplish his romantic effects — was elaborate and calculated.) Then the man’s wife laughed, pointing to the chaperone. “Reminds me of our first date, at the drive-in. My grandmother came and insisted on sitting between us.”

This is what art at its best does; it distills life, using technique to reflect it back to the observer in a way that doesn’t just evoke physical recognition but resonates and stimulates not only intellectually, but emotionally, sensually, and spiritually.

(When I was running a gallery in a small village on the banks of the Nile in the Languedoc region of France, the window display that finally made local passersby stop and look was not the modern paintings, nor my curio shop knick-knacks, nor even my clever hand-drawn comics, but a gargantuan bird’s nest an American neighbor had discovered in the woods.)

When the rodeo wasn’t in town, I’d get my horse fix at the quarter-horse competitions, which show-cased the equines’ ability to herd. So when, picking up Boris Vian’s play “L’equarrissage pour tous” recently, I looked up ‘equarrissage’ and found it translated as “the quartering of horses,” I was confused until French friends explained to me that here the quartering in question is not activated by the horses on straying heifers but imposed on them, post-mortem. (The equarrisseur not to be confused with the chevillard, who hacks horses up for meat.) Vian’s play takes place June 6, 1944, in the Normandy village of Arromanches (where the allies landed 1 million men and set up temporary concrete unloading docks, the remnants of which still peer out of the surf today), chez an equarrisseur more concerned with marrying off his daughter to the German soldier she’s been sleeping with for four years than the bombs rattling the house every few minutes and the steady traffic through his home of American soldiers, German soldiers, an errant daughter who parachutes into the living room with the Russian army and a prodigal son who lands in American military garb. (There’s also an American ordinance officer who, just in time for the wedding, delivers three boxes containing a ready-to-assemble priest, religion joining chocolate and tobacco among the essential provisions furnished by the Allies.) Inconvenient visitors inevitably get bopped on the head and dropped into the pit otherwise reserved for the decomposing horse parts, whose putrid odor is no doubt the reason two French officers finally arrive to announce that the house doesn’t fit in with reconstruction plans, terminating the play by blowing it up with its owner before he can realize the profits the invasion and the accompanying horse carnage no doubt promise, horses (probably Normandy Percherons, known for not being easily rattled by mud or canons) being a vital accessory to and thus recurrent casualty of war. (Vian described his drama as an “anarchist burlesque.” Essentially, he’s saying: Even a good war stinks. My idea is to produce the play on June 6, 2019, in Arromanches, for the 75th anniversary of the Debarquement. Perhaps with marionettes, who might be more resistant than humans to the abuse Vian imposes on his personages to make his point.)

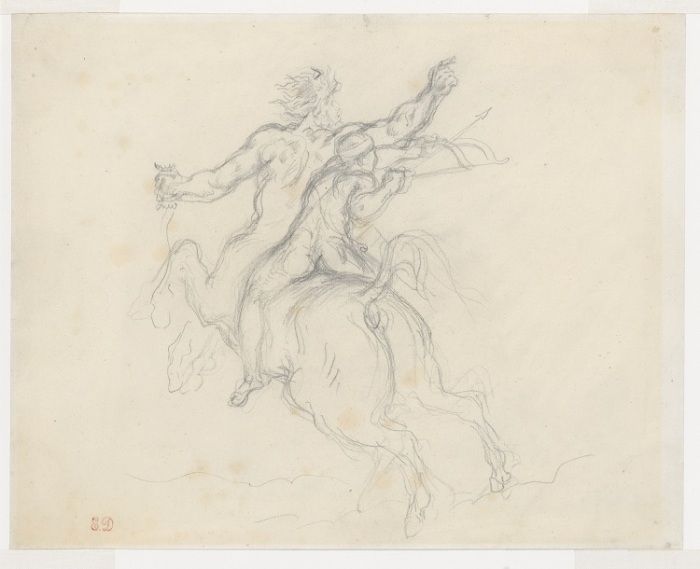

The horse’s historic martial role, as the only thing holding up Achilles, is captured in Devotion to Drawing: The Karen B. Cohen Collection of Eugène Delacroix, opening at the Metropolitan Museum of Art July 17, in this drawing:

Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798–1863), “The Education of Achilles,” ca. 1844. Graphite, 9 5/16 x 11 11/16 inches (23.6 x 29.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift from the Karen B. Cohen Collection of Eugène Delacroix, in honor of Emily Rafferty, 2014 (2014.732.3).

Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798–1863), “The Education of Achilles,” ca. 1844. Graphite, 9 5/16 x 11 11/16 inches (23.6 x 29.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift from the Karen B. Cohen Collection of Eugène Delacroix, in honor of Emily Rafferty, 2014 (2014.732.3).

Like Vian’s play and the Normandy invasion, Laurence Leblanc, whose photography Isabelle Wisniak (remember her?) exhibits June 30 through September 12, also began on June 6, being born on that day in 1967. The photographs on view in Leblanc’s Flair show — at least those which intrigue me the most among what I’ve seen — were taken 40 years earlier in Kentucky (the horses presumably associated with the derby). After discovering them in a dusty album in a rear room at the municipal library of Deauville (Normandy again), Leblanc decided to adjust the original images in a way that re-calibrated the power rapport between horse and man to one of more equilibrium. Take a look at this shot, tweaked by Leblanc:

“Famous Mare 1,” France, 2016. Copyright Laurence Leblanc and courtesy Flair Gallery.

“Famous Mare 1,” France, 2016. Copyright Laurence Leblanc and courtesy Flair Gallery.

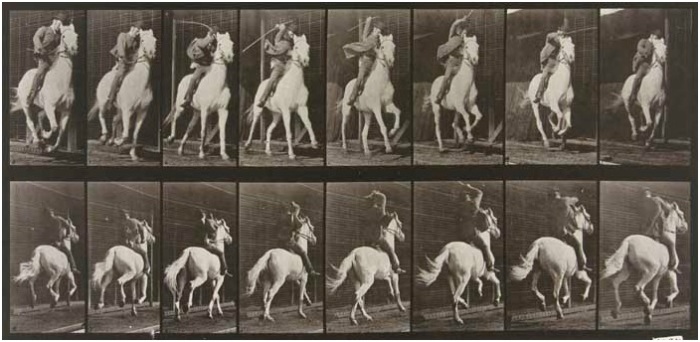

… And then at this one by 19th-century photographic pioneer Eadweard Muybridge, known for his staged photos:

From the exhibition “The Medium and Its Metaphors,” first covered by the AV in 2012: Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904),”Dan with Rider (.064 Second), One Stride in 8 Phases (Left Lead),” ca. 1887. Collotype. Amon Carter Museum of American Art P1970.56.13.

From the exhibition “The Medium and Its Metaphors,” first covered by the AV in 2012: Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904),”Dan with Rider (.064 Second), One Stride in 8 Phases (Left Lead),” ca. 1887. Collotype. Amon Carter Museum of American Art P1970.56.13.

At first glance, the Leblanc made me think of the Muybridge. On closer examination, I realized that in the Muybridge, the rider is beating the horse; in Leblanc’s tweaking of the 1927 photo, the horse is staring down the stable boy (on whom Leblanc seems to have performed a digital equarissage operation), challenging the master-subjugated relationship.

I can’t over-state the global resonances this image by Leblanc, nor another, “Famous Mares No. 3,” suggested to me, nor the personal catharsis they delivered.

What started me on the trail to Wisniak’s gallery was discovering yet another major arts institution whose otherwise noble mission has been compromised, in my view, by the profile of one of its main supporters. In the U.S., this has been most infamously manifest by institutions like New York City Ballet and the Metropolitan Museum accepting large donations from the Koch Brothers (funders of phony science debunking global warming and anti-Labor politicians, among other nefest causes) and, in the case of the Met, the Sackler family (owners of Perdue Pharma, linked to the opiate crisis plaguing the United States, and who have lent their name to the Met wing housing the Temple of Dendur). Instead of getting up on my high horse again and ranting the institution in question, this time I thought I’d try to scout out arts institutions who, in lieu of accepting and parlaying with the world as it is, agitate for the world as it ought to be. By focusing on art related to animals — *and* in a place like Arles with its embedded Tauromaché culture — Wisniak is militating for the cause of animals in the largest sense, getting us on their side by enabling what artists do best: Teach empathy.

On a personal level, contemplating Leblanc’s photos re-imagining the rapport between the horse and the stable boy stirred a memory like those of the Texas cowboys before the Russell watercolor – and, like the protagonist of Herman Hesse’s “Journey to the East,” started me on the road to seeing an episode of my past in a new, more positive light.

Chris, the New Zealand rodeo champion on the Texas pony farm where I fed the humans and helped feed the horses, came from a domain, rodeo, where the goal is not just to master the horse but to show off that mastery. When I met him he was a firm believer in and practitioner of the natural method, which relies more on coaxing, cajoling, and habituating the horses than making them submit with whips and spurs. Neither Chris nor PJ, his deputy, also from New Zealand, wore spurs. (Nor cowboy boots. Nor — demonstrating their confidence that the horses wouldn’t toss them — chaps. Chris preferred holey jeans.) “If you have to wear spurs, you haven’t done your job right,” Chris explained. PJ wasn’t above cursing at the horses if they strayed or dawdled during morning turn-out (the ranch also boarded mares), but he also scolded me (correctly) when I was impatient with the animals, either being too quick to raise my voice when a filly tried to escape her stall in the “mare hotel” I was responsible for watering and cleaning by myself at noontime (a palomino named Cookie was particularly rambunctious) when I entered to scoop the poop, or not pausing long enough between stages when using the graduated scale of coaxing he recommended when I was trying to get the horse to back up while I opened the door of her stall: Start in a whisper, and only increase your tone if the horse doesn’t heed you. “You have to give the horse time to reflect and process what you’re telling her,” he said, in a variation of “You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make him drink it,” the horse in question obviously not being from sage-brush-dry Texas. “If you just keep insisting without pausing to let her absorb what you’ve just said, she gets confused.” It’s a lesson I’ve tried to remember to apply to human relationships, not always with success. (Nor with horses, as the Percheron I tried to lead around the vines – these days, this breed is more likely to be used for farm labor than cat food — during the harvest at a natural winery near Cahors in 2014 will confirm.)

When I insisted PJ watch an episode of Bonanza with me in the bunkhouse we shared, what struck him most was the ponds. “We don’t have those in New Zealand.” PJ loved horses so much that for the six months he was obliged to remain in New Zealand, he worked as a horse truck driver just so he could be near them. One morning I asked PJ how he was doing. “Any day when I wake up to discover I didn’t die in my sleep is a good one.” My own proudest moments came when I was put in charge of feeding a trio including “the blind mare” in a pasture closer to our bunkhouse than the main house, which meant I got to ride the golf-cart out there, usually in the company of several canine passengers who jumped in as soon as I got rolling.

Besides planning and preparing hot meals for lunch and dinner, I also helped PJ with the afternoon feed and stall-cleaning, and eventually took charge of the noon watering and poop-scooping to give PJ more time with Chris, who I was able to watch work with the horses as my other duties allowed. When I made my first dish, a simple quiche, Chris took one bite and proclaimed, “If he can cook like this, I don’t care what he does with the horses.” (I soon earned a reputation in the area as “the French chef,” and if you think this digression is also my way of seeking more work feeding horses and humans, you’re right. The horse-feeding was more complex than you might think. Chris’s wife and collaborator, whom I’ll call Cheryl to protect her privacy and who also taught me a lot, had worked out complex and individualized mixtures of nutrients for each resident of the mare hotel.)

As they enter a Sierra mining camp in Sam Peckinpah’s 1962 “Ride the High Country,” the horses are all that’s keeping Mariette Hartley, Ron Starr, Joel McCrea, and Randolph Scott from looking like what they are: Two greenhorns and two over-the-hill cowpokes. Image courtesy Cinematheque de Toulouse.

As they enter a Sierra mining camp in Sam Peckinpah’s 1962 “Ride the High Country,” the horses are all that’s keeping Mariette Hartley, Ron Starr, Joel McCrea, and Randolph Scott from looking like what they are: Two greenhorns and two over-the-hill cowpokes. Image courtesy Cinematheque de Toulouse.

One late afternoon after I’d finished helping PJ with the feed and stable cleaning and prepared the galette batter for the evening human feed, crossing the pastures that separated the main house from the one I shared with PJ, I decided to take a detour and enjoy my ‘knock-off’ beer (in French, “aperitif”) on a dilapidated couch PJ had installed in the midst of an overgrown field where a baker’s dozen of horses were left to roam. Sinking into the sofa in a position that proscribed a quick exit, I looked up to see 14 very immense horses standing 25 feet away slowly turn their gaze towards me; or as Desnoëttes might put it, “debusquing” me. I can’t say the episode totally evacuated the fear of horses that accompanies my attirance to them. (Much as I’d like to, the human horse hero I identify with the most is not Joel McCrea, but 12-year-old Scarlett Johannsen in “The Horse Whisperer,” alternately drawn to and terrified of the animals after a pal gets fatally tossed by a panicked mount.) But it was the most bare moment I’ve ever had with horses, and one of the most bare moments I’ve ever experienced in my life, just a moment of being: with the animal, with my intimidation in his presence, with advancing to the limit of my fears, as modest as that front may seem in comparison with the dreads that torment others, including my own cowboy heroes; this was my ravine, not navigating its precipitating edges on my pony, but simply approaching them and accepting what that felt like. To share, even if only for a moment, the universe of these belles indifferentes.

I thank Laurence Leblanc — and her gallerist — for helping me revive that moment… and for a catharsis — for isn’t that another vital role of art? — that frees me to dream of feeding horses and humans again, perhaps in a milieu like this one:

PBI’s next destination?: Horses and water in the Camargue, outside Arles.

PBI’s next destination?: Horses and water in the Camargue, outside Arles.

“Famous Mares 3 ,” France, 2016. Copyright Laurence Leblanc and courtesy Flair Gallery.

Have Pen, will Travel: A forward-looking memoir of Paris, the Dordogne, Cahors, Fort Worth, Chicago, Miami Beach, New York, Maryland, Montana, Connecticut, San Francisco, Reno, and the High Sierras

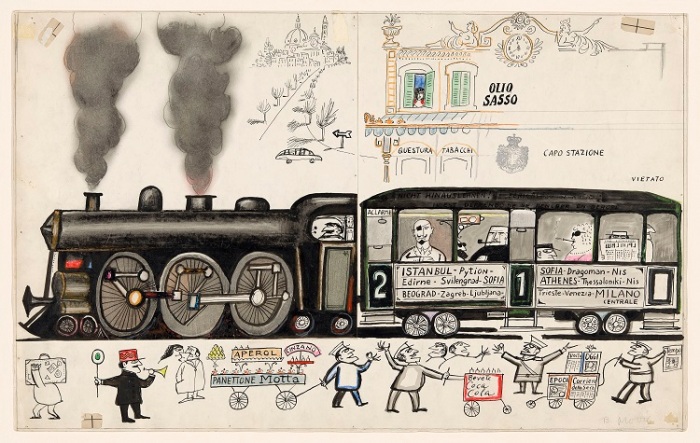

Paul Ben-Itzak’s new 40-page Memoir, including art by Ansel Adams, Robert L. Berry, Lou Chapman, James Daugherty, Gustave Caillebotte, Jacob Lawrence, Sylvie Lesgourgues, David Levinthal, Roy Lichtenstein, Sam Peckinpah, Charles M. Russell, Saul Steinberg, and Frank Lloyd Wright from both current exhibitions and the AV Archives, is now available. To receive your own copy as a PDF or Word document, including 35 illustrations, please send $19.95 to the AV by designating your PayPal payment to paulbenitzak@gmail.com, or write us at that address to learn about payment by check. Your purchase includes a complimentary one-year subscription to the Arts Voyager and Dance Insider ($29.95 value). Above: Saul Steinberg, “Train,” From the exhibition Along the Lines: Selected Drawings by Saul Steinberg, on view through October 29 at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Paul Ben-Itzak’s new 40-page Memoir, including art by Ansel Adams, Robert L. Berry, Lou Chapman, James Daugherty, Gustave Caillebotte, Jacob Lawrence, Sylvie Lesgourgues, David Levinthal, Roy Lichtenstein, Sam Peckinpah, Charles M. Russell, Saul Steinberg, and Frank Lloyd Wright from both current exhibitions and the AV Archives, is now available. To receive your own copy as a PDF or Word document, including 35 illustrations, please send $19.95 to the AV by designating your PayPal payment to paulbenitzak@gmail.com, or write us at that address to learn about payment by check. Your purchase includes a complimentary one-year subscription to the Arts Voyager and Dance Insider ($29.95 value). Above: Saul Steinberg, “Train,” From the exhibition Along the Lines: Selected Drawings by Saul Steinberg, on view through October 29 at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Conspicuous by its absence: “Ashcan” in the dustbin = mid-measure for ‘Stuart Davis In Full Swing’ Expo in San Francisco

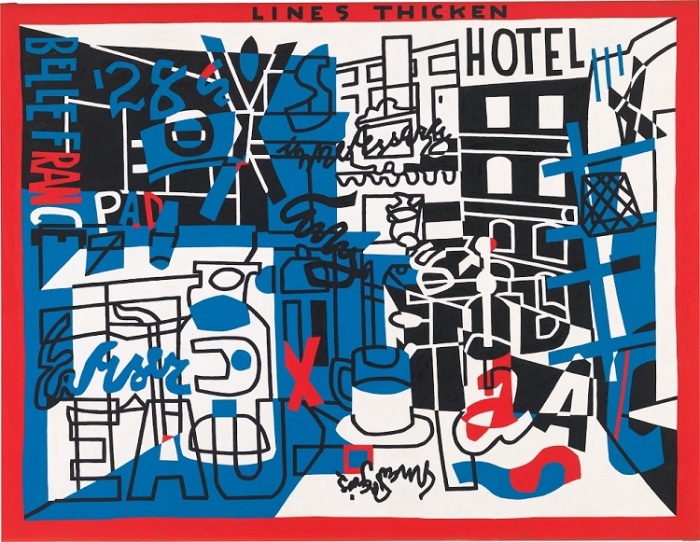

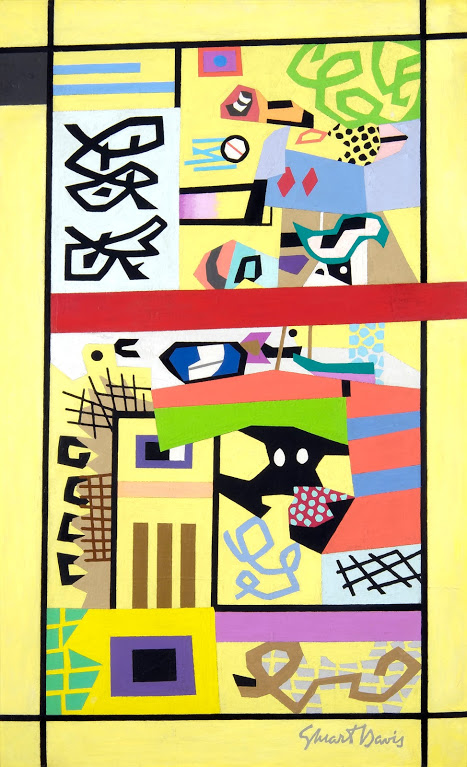

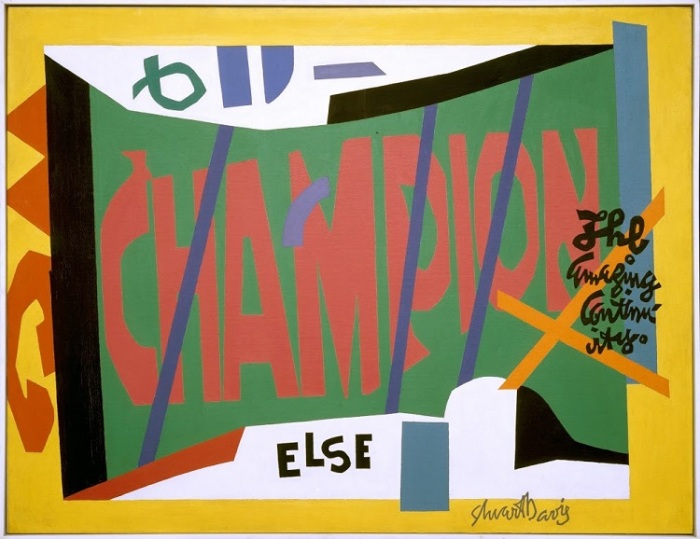

Stuart Davis, “The Paris Bit,” 1959. Courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Stuart Davis, “The Paris Bit,” 1959. Courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

By Paul Ben-Itzak

Text copyright 2017 Paul Ben-Itzak

Like what you’re reading? If you’re not already a subscriber, please make a donation today to the Arts Voyager. You can donate via PayPal by designating your payment to paulbenitzak@gmail.com , or write us at that address to learn how to donate or subscribe by check.

After having pilloried recent exhibitions at the Centre Pompidou for being too monographic — the everything but the kitchen sink Corbusier cavalcade was pretty crammed to the hilt for what was supposed to be an homage to a master of efficient space management, while the Paris institution’s Wilfredo Lam show should have turned off the spigot after 1950, when Lam’s tropical jungle canvasses started becoming monotonous — I’m aware it might seem contradictory to complain that the exhibition Stuart Davis, In Full Swing, on view at San Francisco’s de Young museum through August 6 before moving on to Arkansas’s Crystal Waters, omits a vital chapter in the Abstract Expressionist’s career. The omission is important, because unlike the apprentice paintings of Duchamp and Picasso, which only demonstrated that they’d mastered the basics of composition before deviating from them but were not significant for their intrinsic value, Davis’s contributions to the early 20th century fount that was the Ashcan School, starting when he was still a teenager, also prove that his social activism (notably as head of the Artists’ Union) wasn’t isolated from his painterly activity, but sprung from the same well.

Davis’s 1912 canvas “Chinatown,” for example, isn’t just a slice of Lower East Side topography, but a portrait of the desperation driving those women who weren’t going up in flames in locked factory fires into selling their bodies to survive. (The painting is part of the permanent collection of Fort Worth’s Amon Carter Museum of American Art, whose founders identified Davis as one of their core artists around whom they decided to build their stock.) The omission of work from the seminal part of his career that most directly responded to social conditions is particularly boggling given museum director Max Hollein’s declaration that the de Young “has always believed that artists have a duty to comment and critique our culture and we are pleased to show how one American artist responded to the tumultuous times he lived through.” Leaving aside that the ludicrous pretension of this statement is more a reflection of the social-message driven San Francisco aesthetic (and I’m a native) than a directive any artist worth his sourdough starter would take seriously, *having made such a profession of faith*, to then ignore the very work that meets this definition in the exhibition Hollein is putatively promoting is incomprehensible.

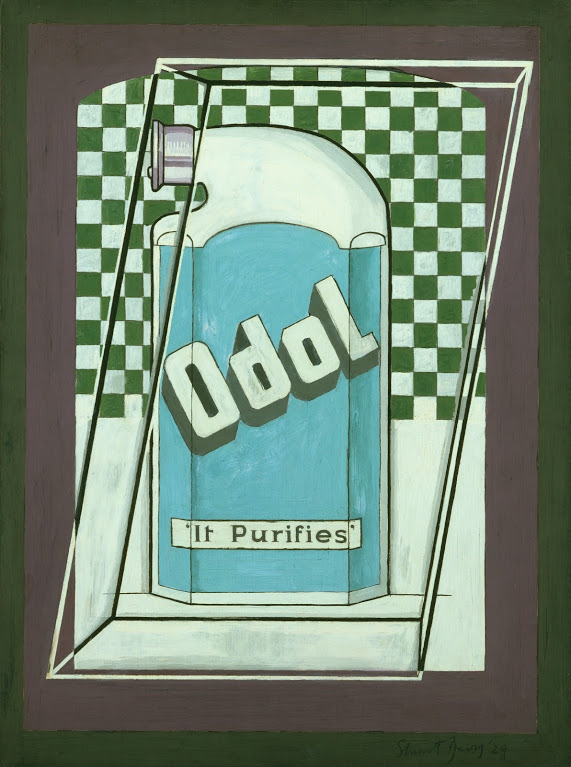

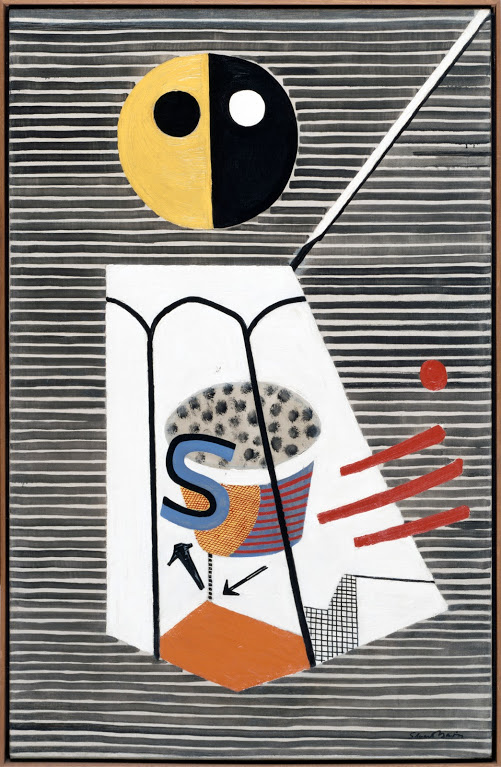

Perhaps deserving more leniency is the misapprehending of Davis’s later work by New Yorker critic Peter Schjeldahl, in his review of the exhibition’s tour at the Whitney last year, as “proto-Pop Art,” perhaps a mis-reading of curator Emma Acker’s statement that Davis’s “appropriation of images from consumer culture and advertising in the 1920s… predates 1960s Pop Art.” In fact, where Pop Art more often than not simply re-envisioned commercial icons as Icons — the only ingredient Andy Warhol added to Campbell’s Tomato Soup cans was his marquee name — Davis actually worked in the opposite sense. Rather than elevating pop “culture” into art, he inserted its ready symbols and recognizable images into his abstract and semi-abstract art to offer an anchor or key which would help viewers identify with the abstractions, perhaps his own manner of resurrecting the ubiquitous key in the medieval Unicorn tapestries on view at the Cloisters museum in New York, where Davis installed himself when he was just 15 years old.

Stuart Davis, “For Internal Use Only,” 1944-45. Courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

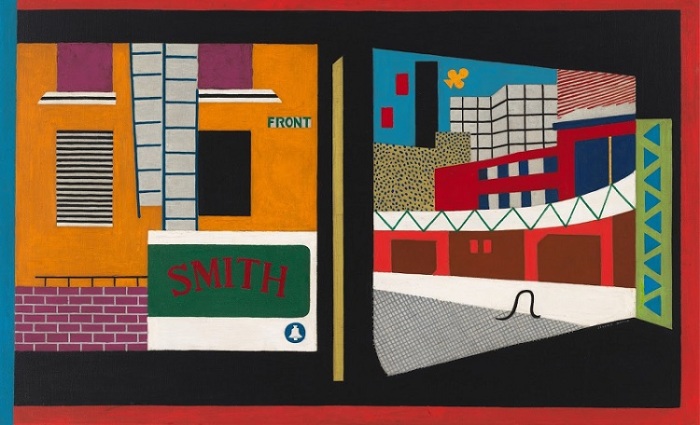

Stuart Davis, “House and Street,” 1931. Courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Stuart Davis, “Odol,” 1924. Courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Stuart Davis, “Egg Beater No 2,” 1963-64. Courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Stuart Davis, “Egg Beater No 2,” 1963-64. Courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Stuart Davis, “Salt Shaker,” 1931. Courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

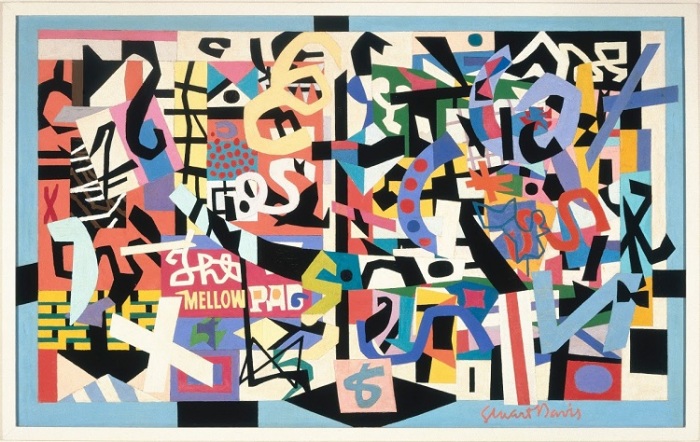

Stuart Davis, “The Mellow Pad,” 1945-51. Courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Stuart Davis, “The Mellow Pad,” 1945-51. Courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Stuart Davis, “Blips and Ifs,” 1928. Courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Stuart Davis, “Owh! in San Pao,” 1951. Courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Stuart Davis, “Rapt at Rappaports,” 1951-52. Courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

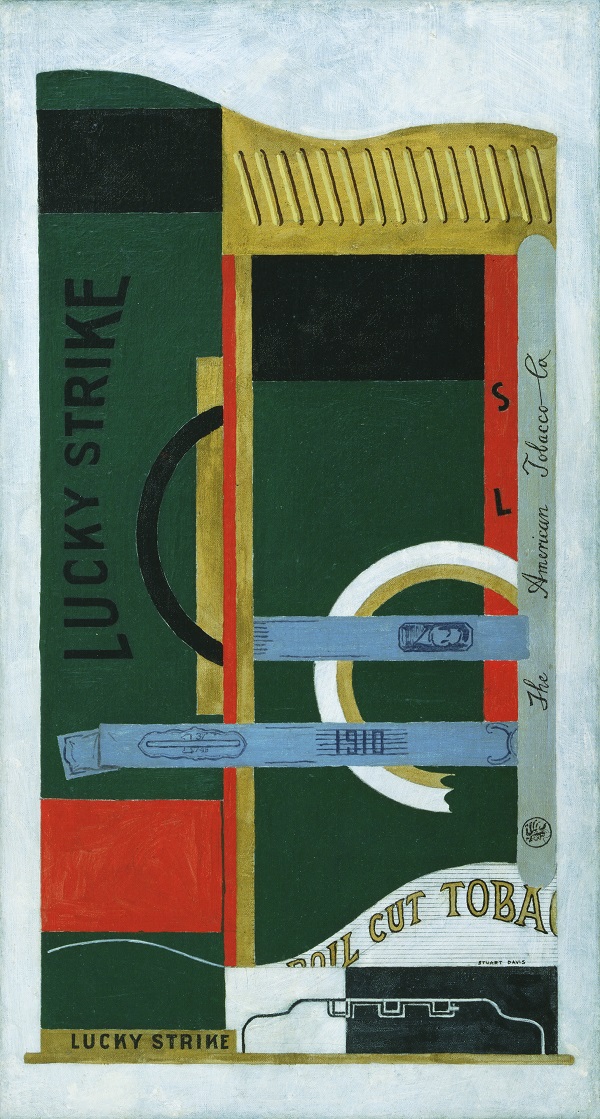

Stuart Davis, “Lucky Strike,” 1921. Courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Stuart Davis, “Visa,” 1951. Courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

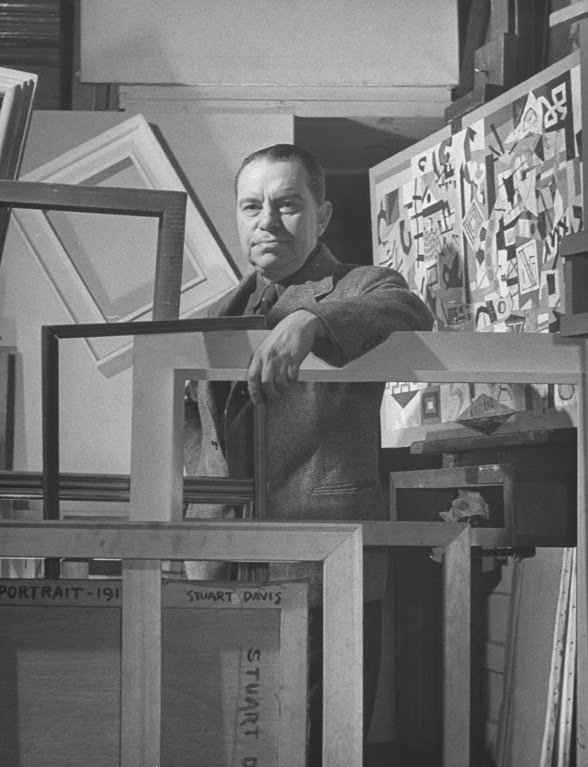

Stuart Davis in his studio.

Want more? Click here to see examples of some of the Stuart Davis works in the Crystal Waters collection.

Protected: From the Archives: An American Panorama at the Amon Carter in Fort Worth, Texas

Sonnez la matine: La Culture, c’est pas une ‘annexe’

Around the world, French culture is its calling card

“Même si les civilisations successives étaient des organismes, et semblables, la nôtre montrerait deux caractères sans exemple. D’être capable de faire sauter la terre ; et de rassembler l’art depuis la préhistoire.”

— André Malraux, Néocritique*

By Paul Ben-Itzak

Copyright 2017 Paul Ben-Itzak

Once upon a time, France’s siren call to the world was its culture, of which the most potent register was its literature. And yet today, this siren call has often been drowned out, or at least muffled — and, at Charlie Hebdo, literally assassinated — by the threat of and acts of terrorism, unfortunately resulting in a state of siege mentality on the part of many. The knee-jerk response to the real and present threat of terrorism in some quarters — in the U.S. as in France — has been to in effect cede to the terrorists by being terrorized, putting up walls, ostracizing the Other, and erecting a citadel we like to think will be impregnable but that risks to swallow us in solipsism. And the understandable and completely justifiable responses of military Defense and verbal Sanction have been under-accompanied by strategies to treat the problem at its roots. To put the question concretely: How to head off that child at risk before s/he becomes a teenager and, in that stage of life so subject to alienation, potentially fertile territory for the manipulation and brainwashing of the ideologues and terrorists?

In France, the tragedy has been that the ‘better offer’ has always been there: In its culture, in ideas, in philosophy, and in the ‘lumieres,’ as they’ve been handed down in the country’s LITERATURE.

To behold this rich heritage and potential anecdote to Obscurantism being so under-exploited has been particularly tragic for an American who from the moment he could have stories read to him has been seduced by the siren call of French and Francophone culture: Babar, “Madeline” (technically not written by a Frenchman, but qualified by its rebel spirit and its luminous setting: PARIS), Tintin and, later, through the lyrics of song, Jacques Brel, Yves Montand, Jacques Dutronc, Serge Gainsbourg…. (Indeed, the first music I remember mimicking is not “Michael row your boat ashore” but “Frere Jacques, Frere Jacques, dormez vous, dormez vous?”) And if we extend the literary rubric to film — also, after all, a form of composition — “The Red Balloon” planted the siren of the Belleville neighborhood of Paris in my young head and heart and, later, Truffaut and Godard made their respective imprints with Gallic right and left brains which mined the poetry in romantic as well as societal strife.

I am not the only American who has been drawn to this heritage. (In some cases, more even than the French themselves. During an initial sojourn in Paris in 2001, accustomed to lines around the block for his films in New York and San Francisco, I was shocked to find that Godard’s “Eloge d’Amour,” fresh from Cannes, was allocated the tiniest screen in the tiniest room of a multiplex near the Luxembourg Garden, where all of 10 people watched his latest experimentations. My French actress friend clutched her head in agonized frustration, while I — at that juncture French illiterate — remained perched on the edge of my seat for the entire picture.)

So you can imagine my chagrin in reading, just before the recent presidential election, New York Times columnist Roger Simon’s “France at the End of Days,” a one-sided portrait of a supposedly crepuscular France in which the Neo-Xenophobes were battling the Neo-Liberals for control of the wheel that would determine the country’s direction for the next five years. (Nowhere in the article was it explained that if the National Front had doubled its support since the last election in 2012, it wasn’t because an additional 17 percent of Frenchmen and women suddenly woke up racists, but because a)like my retired neighbors here in the Southwest of France, they’re weary of making their grocery purchases every week based on what’s on sale, and b) the end run by leaders of both the principal parties around the popular rejection of the European Constitution in 2005 with a Treaty of Lisbon not subject to popular confirmation, capped by Francois Hollande’s running in 2012 as “the enemy of Finance” only to (in the view of some; I’ll take the Fifth) embrace Capitalism after he was elected president left many voters disillusioned with the establishment parties.)

Hollande didn’t do much better with the cultural agenda, all three of his cultural ministers qualified more by their allegiance to the Socialist party than their cultural accomplishments. The low point was a minister who, asked to name her favorite Patrick Modiano work after the latter won the Nobel Prize, couldn’t name a single title, finally explaining that she didn’t have time to read books, as her most famous predecessor André Malraux no doubt jumped out of his grave.

So when Emmanuel Macron, asked during the 2017 presidential campaign about his cultural program, said that a pillar would be expanding library hours at night and on the week-ends, I was encouraged.

In the lower-class, mixed, crime-ridden neighborhood of East Fort Worth, Texas where I lived before returning to France, the library was always packed — most of all with young people, often bilingual. (As was the library’s small collection.)

The Library is a crucial point of First Contact with Culture.

The Library is a social nexus that provides a constructive alternative to hanging out with and getting recruited by gang-bangers.

Or terrorists.

And, unlike many other cultural outlets, it’s free. And it’s accessible, in the neighborhood.

And yet, around the world, library hours have been eviscerated and libraries shuttered for the past 30 years. (In the Anglophone culture, this is what we call Penny-wise, pound-foolish.)

With Emmanuel Macron, elected president May 7 with a 66 percent majority, increasing library hours is not just a pat solution. This is a man who carefully chooses his words. During his presidential debate with National Front candidate Marine Le Pen, after two hours of not taking the bait and remaining calm, he finally called her and her party “parasites.” This was not an ill-considered empty put-down but an exact diagnoses; parasites feed on bodies whose immune systems have been weakened. (Also along the lines of better immunizing the country’s infants, Macron has pledged to cut class size in difficult neighborhoods in half, to 12 students.)

And yet for France, it doesn’t have to be this way. Words — words — build up immune systems. They build up our defenses against ignorance, against intolerance, against fear, against pain, against hate, against ‘fermeture.’ I’d even argue that they forge pretty solid inroads against mortality because, as Albert Moravia once pointed out, they augment our existence laterally with a multitude of other lives… and cultures.

But let’s pause on that word Defense.

In analyzing the cabinet named yesterday by Macron and his new prime minister, Edouard Philippe (also a book maven, having launched book-mobiles around his coastal city of Le Havre), most of the media I audit has been commenting that even if half the 22 members are women, only one, the new minister of armies, was accorded a ‘regalian’ ministry. (I can’t find this word in any of my French dictionaries, so it must be a recent — Franglaise? — innovation of the political pundits.)

One Radio France reporter even grouped the ministry of Culture and Communication with those he dubbed ‘annex’ ministries.

This in France, the cradle of literature.

Never mind that the most ‘regalian’ of French presidents in the 60 years of the Fifth Republic, the man still more likely to be referred to by the French as “the General” than “the president,” Charles De Gaulle, appointed as his first and long-time minister of culture André Malraux, himself a Nobel laureate.

The General understood that Culture was not an ‘annex,’ but a pillar of national defense and an essential component of the foundation of a society. And that the best way to protect a nation’s heritage is not to pillory other cultures but to incorporate them in the national cultural identity. (As for Macron, he did not, as some media here inaccurately reported, say that there was no such thing as French Culture, but that it was rather a question of French cultures.)

Francois Mitterand — another literary president — understood this too, appointing Jack Lang to incorporate contemporary elements into the French cultural vision and agenda. (It was Lang who implemented the now European-wide Fete de la Musique, coming up this June 21, just when we’ve got something to dance about.) As did even Nicolas Sarkozy, appointing to the post Mitterand’s nephew Frederick, whose outsized erudition would certainly qualify him as ‘regalian.’

Another normally astute Radio France commentator alleged Wednesday that Macron, seeking gender equilibrium in prime minister Edouard Philippe’s cabinet, had called a cultural figure and asked him to provide the names of three women who worked in the sector. Setting aside that this allegation may be the product of a ‘mauvaise langue,’ I’d respond: “Et alors?” Admitting the possibility — if the story is true — of a latent sexism in the idea that Culture is a ‘woman’s ministry’ and thus only fit for dames and pansies, isn’t this an improvement on the procedure followed by François Hollande, who seemed to choose his cultural ministers not for their cultural currency but on the bit-coin of party loyalty?

Macron’s eventual choice, Françoise Nyssen, definitely has cultural credibility. The long-time director of Arles-based Actes Sud, founded by her father in 1978 and since grown to one of France’s most respected publishing houses, Nyssen’s authors include Salman Rushdie, Paul Auster, and Kamel Daoud. The author of “Mersaut: Counter-Investigation,” a response to Albert Camus’s “The Outsider,” and an independent thinker unafraid to criticize Occidental or Oriental mores, Daoud has also described Camus himself as the last Outsider, a man with no country. (Following the suicide of her son, Nyssen also founded a school focused on listening to children, the School of Possibilities.)

… Or, I’d argue, multiple countries — like Nyssen, an immigrant whose publishing house excels in promoting authors in translation; thus eminently French and open to the world. Not so anecdotally, Arles itself is best-known outside France for having welcomed Vincent Van Gogh, yet another foreigner who expanded French culture even as it assimilated him. (These days, also not so anecdotally, the Provencial city is home to ATLAS, the country’s leading association for literary translation.)

As have so many of us (assimilated French culture), even those who rarely set foot in France. Take Ludwig Bemelmans, the author of the “Madeline” series of children’s adventures, whose courageous heroine exemplified the Gallic strategy of responding to terror with words during a visit to the Paris zoo:

“To the tiger in the zoo

Madeline just said, ‘Pooh-Pooh.'”**

*Published in “Malraux: Être et Dire,” with texts assembled by Martine de Courcel. Plon, Paris, 1976. Copyright André Malraux.

**From “Madeline,” copyright Ludwig Bemelmans, 1939, renewed Madeleine Bemelmans and Barbara Bemelmans Marciano, 1967.

Open Studio Policy

Poster designed by Michèle Forgues and Federica Nadalutti, and courtesy Ateliers d’Artistes de Belleville. Click here to read the Arts Voyager’s coverage of last year’s Open Studios / Portes Ouvertes de Belleville, and here to read our essay around the 2010 edition. And for more details on this year’s version, go here.

Poster designed by Michèle Forgues and Federica Nadalutti, and courtesy Ateliers d’Artistes de Belleville. Click here to read the Arts Voyager’s coverage of last year’s Open Studios / Portes Ouvertes de Belleville, and here to read our essay around the 2010 edition. And for more details on this year’s version, go here.

Sponsor Ads Available for Arts Voyager Spring & Summer Paris coverage

Affordably-priced Sponsor ads are now available for the Arts Voyager’s upcoming coverage of performances and exhibitions from all over the world coming to Paris this Spring and Summer. Rates start at just $69 when you sign up before May 15. For more information, e-mail paulbenitzak@gmail.com by pasting that address into your e-mail browser.

Europe at the Crossroads: Portes Ouvertes de Belleville & the Prè Saint-Gervais, Performers from Around the World — Artists Converge on Paris; Help the Arts Voyager be there

Parce que oui, la Culture française – comme d’ailleurs tous les cultures qui déferle vers Paris – appartient au monde qu’elle a si souvent rayonné, et il faut refusé de la laisse etre confiné et sequestré par les forces de l’Obscurantisme.

For subscription and sponsorship opportunities starting at $69, contact Paul Ben-Itzak at artsvoyager@gmail.com.

The Open Studios or Portes Ouvertes de Belleville and those of the Prè Saint-Gervais, performers including Berlin’s Constanza Macras, Portugal’s Vera Mantero, a major exhibition devoted to Camille Pissarro paintings rarely seen in France, Belgium’s Alain Platel, Spain’s Israel Galvan, Crystal Pite — these are just a few of the major cultural happenings in Paris and environs this Spring that the Arts Voyager and Dance Insider will be able to cover with your support.

Many of you first read about these internationally renowned artists and events for the first time in English in our journals and, continuing our 20-year mission of bringing you stories not told elsewhere, we’ll also be reporting on Giulio D’Anna, a Netherlands-based Italian choreographer whose “OOOOOOO” is inspired by Zagreb’s “Museum of Broken Relationships,” and Jasna Vinovrski’s “Lady Justice,” addressing the relationship between justice and art. Speaking of art, we’d also like to bring you Yasmina Reza’s “Art” as interpreted at the Theatre de la Bastille by the pioneering Belgium theater company STAN . And of intersections between art and society, this year’s Chantiers (Building Projects) d’Europe festival at the Theatre de la Ville features countries in the front lines of the refugee crisis, notably in six short films from Greece addressing this topic and a public brainstorming session with artists from six countries. Most of all we’ll be able to bring you into the studios of the 200+ artists taking part in the Open Studios of Belleville — a neighborhood which in its very MULTI-CULTURAL contours and dimensions provides the best retort to the cloistered vision of French culture represented by the National Front. (We share the FN’s stated pride in traditional French culture; we simply argue that this definition is too limited and does not do justice to the grandeur and ouverture to the world that has always been French culture.) Click here to read our coverage of last year’s Open Studios / Portes Ouvertes de Belleville.

Already a subscriber or sponsor? Please forward this story to your colleagues. Want to become one? Contact us at paulbenitzak@gmail.com . Subscribers receive full access to our 20-year archive of more than 2,000 reviews by 150 leading artist-critics of performances on five continents, plus five years of the Jill Johnston Letter as well as Arts Voyager art galleries, film reviews, and travelogues from Paris, New York, and across the U.S.. Sponsors receive this plus advertising on The Dance Insider, and/or the Arts Voyager.

France, too, is at the crossroads. On May 7 the country will choose between the fear represented by the National Front and the hope and optimism represented by Emmanuel Macron. Between closure and opening. In the campaign between these two ‘cultures’ that has raged in this country for the past two years, CULTURE has been all but forgotten. (Among Macron’s refreshing ideas: More library hours.) With your help, we will be able to do our part in restoring some light to what has always been France’s principal calling card around the world. Our calling for more than 20 years.Many thanks and

Cheers,

Paul

artsvoyager@gmail.com