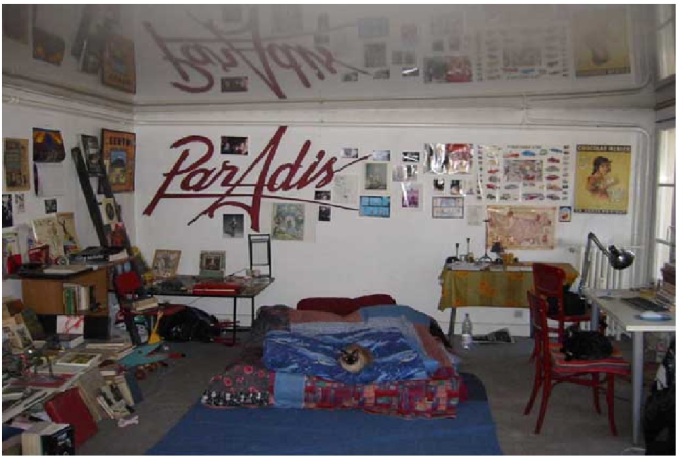

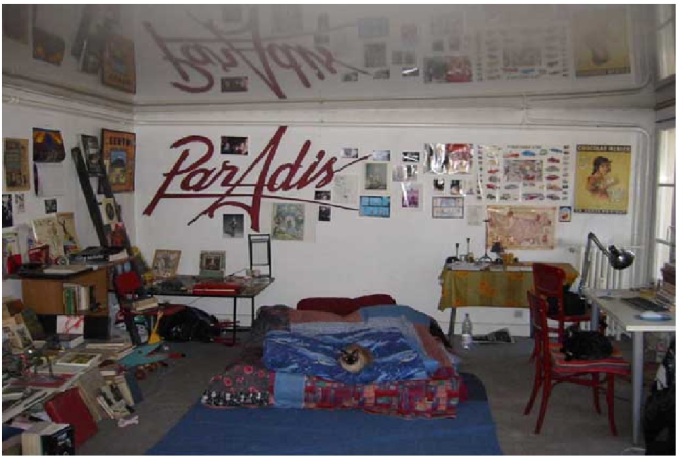

The apartment at 49, rue de Paradis, several years after we moved in on November 28, 2001. At the time of this chapter, it was empty. Except for the cats: That’s Sonia the Alaskan on the bed, Hopey the San Franciscan on the chair at right, and Mesha the other Alaskan is no doubt looking out at the balcony from the cat window. (See below.) Note mylar ceiling. Photograph copyright and courtesy Christine Chen.

The apartment at 49, rue de Paradis, several years after we moved in on November 28, 2001. At the time of this chapter, it was empty. Except for the cats: That’s Sonia the Alaskan on the bed, Hopey the San Franciscan on the chair at right, and Mesha the other Alaskan is no doubt looking out at the balcony from the cat window. (See below.) Note mylar ceiling. Photograph copyright and courtesy Christine Chen.

By Paul Ben-Itzak

Copyright 2012, 2016 Paul Ben-Itzak

Paris eternelle, petites mortes fugitifs

For Noemie Gonzalez, a California girl who came to France to look for eternal Paris, only to find a bullet waiting for her on a café terrace near the Canal St.-Martin.

Princeton, 1982: The Flatbush-born Romantic Literature professor with the ersatz French accent was explaining to an auditorium full of students many of whom were drawn to Princeton by Scott Fitzgerald ‘17’s “This Side of Paradise” that the protagonist of Jean-Paul Sartre’s “La Nausée” “sees himself as if he’s in a film. And of course, no normal person would think this way.”

Besides following the path of Antoine Doinel and searching for the femme de ma vie as had Truffaut’s hero, another goal I had when I moved to Paris in July 2001 was to insert myself into paintings I’d heretofore only observed on museum walls. (Neither scenario envisioning Picasso’s “Demoiselles d’Avignon.”) In this light, the view from my new balcony at 49, rue de Paradis, where I and the cats installed ourselves on November 28, was as promising as the girl who awaited me in the non-functional salle de bain as I took my shower in a kitchen sink squeezed under vermillion cubbards one evening just before Christmas: Across the street, at 58, was the former studio of Camille Corot, where the father of pleine air painting had given Pissarro (and, later, Berthe Morisot) his first Paris lessons in color values.

“It has a small balcony,” the proprietor, Helene Valoire, had told me when I’d called to see the place in late October. But the only thing that was small about this balcony, which stretched the length of the three French windows in the salon / bedroom / dining room, was its narrow depth, I discovered when I arrived and looked up at the 5th floor. The two mahogony doors of the building’s entrance, high enough to accommodate horses (as they once did), were flanked by brass serpents turning green. At the top of the spiral staircase but one (a sixth floor housed former servant quarters converted into studio apartments, usually occupied by twenty-something students and workers; you had to be young not to expire from the climb; at 40 the day I moved in, I was the oldest person living on the 5th floor or above), a rickety door opened to the apartment’s narrow entrance whose floor, on the day I first tread on it, was dirt, as was that of the salle de bain behind the second door on the right (the first opened to the toilet), directly facing the small kitchen, also with its own (albeit hollow) doorway. (The Napoleonic Civil Code requires there be two doors between the bathroom and the kitchen. I’ve seen apartments where the two doors are right on top of each other with nothing in between, just to accommodate the code.) An opening of about 3 x 4 feet looked out onto the main room from the kitchen; its ledge would become the cats’ dining room.

The balcony (cat window in foreground), with the view towards the rues Poissonniere, Bleue, and Papillon. Turning right at the corner lead eventually to Montmartre. Turning left to the Grands Boulevards. (For more itineraries, see below.) The first complete building across the street is where Corot taught color values to Pissarro and Morisot. Photograph copyright and courtesy Christine Chen.

The balcony (cat window in foreground), with the view towards the rues Poissonniere, Bleue, and Papillon. Turning right at the corner lead eventually to Montmartre. Turning left to the Grands Boulevards. (For more itineraries, see below.) The first complete building across the street is where Corot taught color values to Pissarro and Morisot. Photograph copyright and courtesy Christine Chen.

If I was getting to see the place before it went on the market, it was because Mme Valoire had been planning to sell the apartment, but after learning the building itself had major foundation problems, had decided to put that off.

“Why does the floor slant?” I asked her; the rake made the living/bedroom look like the villains’ lairs from the ‘60s “Batman” television series. “Don’t worry,” she said, laughing. “It’s normal. All the buildings in the quartiere are like this.” Then, pointing up at the white mylar sheet covering the entire ceiling and at my own reflection, I asked, “What’s that for?” “It’s because you don’t want to see what’s above it.”

The French prize proprieté (my three-year lease included a requirement that tenants lead a ‘bourgeoisie lifestyle,’ which the landlord explained just meant no drying laundry on the balcony), so Mme Valoire would have preferred that I wait another month until the apartment was really ready. When I pleaded that I didn’t have any place else to go, she let me move in early but said she would not charge me for the first month. For that period, I’d have to take my showers in the kitchen sink as the tub wasn’t yet installed in the bathroom, which she was having re-done with ivory-colored Italian tiles. (My downstairs neighbors at 49 would later marvel that my bathroom was as big as their kitchen and my kitchen as small as their bathroom.) At that point — December 2001, when the imminent Euro was worth 11 cents less than the dollar — the apartment was half the cost (in U.S. $) and twice the size (42 meters squared not counting the balcony) of the Greenwich Village apartment next to Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Lady that I and the cats had just left after six years — about $570/month. The French windows were also being replaced by a ‘double-vitrage’ variety and the balcony re-soldered. (I’d later put chicken wire over one of the windows so that I could air the apartment without the cats getting out. It also proved convenient for drying my laundry en caché.) Consequently, when I moved in with the cats, my new home was already occupied, by a half-dozen workers, presided over by a jovial giant of a plumber. They’d arrive every day and change into their work coveralls in my living room. I loved the bonhomie of having the workers there. Sometimes I’d even wave to them on my balcony as I returned home, and they’d wave back. Every morning I’d offer them coffee when they arrived, which they thought was peculiar but which they accepted with pleasure.

Left: the rue Lafayette, which leads to the Opera House. Right: The view from the balcony down the rue de Paradis, which leads eventually to Fidelite, the rue St.-Denis, the Gares de l’Est et Nord, and the Canal St.-Martin. Photograph copyright and courtesy Christine Chen.

Left: the rue Lafayette, which leads to the Opera House. Right: The view from the balcony down the rue de Paradis, which leads eventually to Fidelite, the rue St.-Denis, the Gares de l’Est et Nord, and the Canal St.-Martin. Photograph copyright and courtesy Christine Chen.

The first day that I had to leave the apartment with the workers still there, I taped a note on the middle window (this was before I’d put the chicken wire up) asking them to please keep the windows shut so the cats couldn’t escape, signing it, “Le locuteur,” when I should have written “le locataire,” or “the tenant.” Marc, my new friend who’d sublet me the place on the Square Albin Cachot with the catastrophic plumbing, cracked up when he saw this. “You wrote, ‘He who speaks.'”

The ongoing apartment construction was a good excuse for He Who Speaks to get out of the house and explore his new neighborhood, ideally situated for He Who Searches to Insert Himself Into La Paris d’’Autrefois.

Crossing the street from the 10th arrondissement into the 9th at the catty corner of Paradis, Papillion, Poissonniere, and the rue Bleue and heading down to the rue Bergere took me to the Folies Bergere, where in the 1920s Josephine Baker had introduced jazz to Paris. The street was also, reverse-serendipitously as far as this California Jew who felt more at home amongst Rainbow Tribes was concerned – my mother had once dallied with something called the Acquarian Minyon — home to an over-priced kosher restaurant, super-market, bookstore, Jewish supplies boutique, and discrete Orthodox temple. Heading up Papillion from Paradis and turning left at Lafayette (“I am here!”) — after passing the Square Monthion, where a metal “France has lost a battle, but not the war!” note from General De Gaulle dated June 18, 1940 guarded an alabaster statue of three buxom Belle Epoch women honoring workers – conducted me to the Opera House, where Emma Livry, protegée of Marie Taglioni (the first to dance on point), went up in flames not long after making a debut in Taglioni’s ballet “La Papillion.” (Covering Livry’s funeral procession in 1863 for Le Moniteur, Theophile Gauthier, Il St. Louis hashish den-mate of Baudelaire, lamented: “She resembled so much the butterfly; like him, her wings were burned in the flame, and, as if they wanted to escort the convoy of a sister, two white butterflies flew without rest above the white coffin during the trajectory from the church to the cemetery. This detail that the Greeks would see as a poetic symbol was remarked upon by thousands of people, because an immense crowd accompanied her funeral cart. On the simple tomb of the young dancer, what epitaph to write, if not that found by a poet of the Anthology for an Emma Livry of the Antiquite: ‘Oh earth, be light on me; I weighed so little on you!'”)

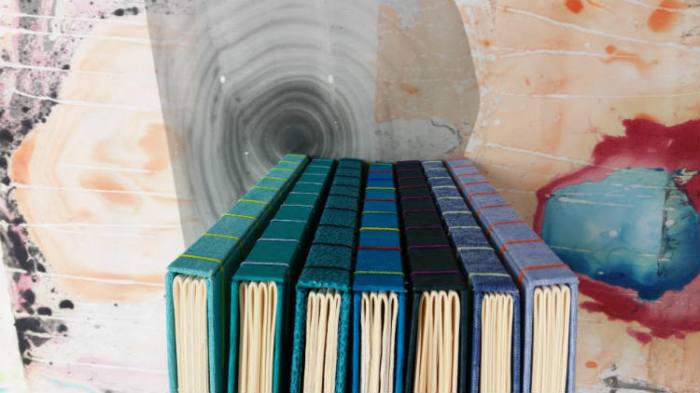

Background: The ‘cat perch’ leading to the kitchen. Foreground: A door converted into a book table, where the stars include several of the important women in the author’s life, such as Leonor Fini, Kate Bush, Josephine Baker, Brigitte Bardot, Madeline, and others. Photograph copyright and courtesy Christine Chen.

Background: The ‘cat perch’ leading to the kitchen. Foreground: A door converted into a book table, where the stars include several of the important women in the author’s life, such as Leonor Fini, Kate Bush, Josephine Baker, Brigitte Bardot, Madeline, and others. Photograph copyright and courtesy Christine Chen.

If in lieu of continuing straight down Lafayette towards the Opera House I took a sharp right at the square and then a diagonal left, after passing a 19th century Portuguese synagogue (next to the Algerians, the Portuguese make up the single largest immigrant community in France), I’d eventually end up back at 33, rue Lamartine, one-time demeure of Baudelaire, PBI, and, still in that Fall-Winter of 2001, Sabine. Turning right at the end of Sabine’s block and hiking up Martyrs brought me to Montmartre. Various detours to the left off Martyrs as Sacre Coeur emerged from “La Butte” (as the top of Montmartre is called) and then veering up to Clichy took me past the homes and/or ateliers of Renoir, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Degas; the former locations of the shop where Cezanne traded canvases for pigment powder to mix brand new colors and of the Chat Noir, where Alphonse Alias once held forth with his insolent poetry and Erik Satie contributed the occasoional ditty; and, on a gated alley just before Pigalle (or, as the U.S. soldiers looking to buy ‘petites mortes’ from elderly prostitutes after the Liberation referred to it, “Pig Alley”), the long-time home of Jean Renoir. As for stepping into the paintings, I was disappointed to find that not only was the Square Adolphe Max / Vintemille, right below the Moulin Rouge, more petite than the one depicted by Vuillard from the atelier/apartment overlooking the square he shared with his mother, but the grass presided over by a bust of Berlioz was made of astro-turf.

If instead of mounting Martyrs at Lamartine I crossed it and continued along the rue St. Lazaire – after a nod at Notre Dame de Lorette, where Van Gogh once paused before heading down to the Grands Boulevards to pitch his paintings to Goupil — I eventually came to the train station immortalized by Zola in “La Bete Humaine” and Monet in gauzy depictions of the locomotive ‘beasts’ clouding up the station with steam. (Along St.-Lazaire, I could also take a side-track to the former home and studio, now museum, of Gustave Moreau, its walls plastered with Ledas and her Swans, Salomés and Jean le Baptistes, and lolling naked sylphs caressing unicorns.) In memory of Zola’s doomed adulterous lovers (from the same book) nibbling on a Sunday chicken in their roost near the station while they plotted the demise of the woman’s husband, I’d sometimes buy a delectable chicken roasted with garlic at a rotisserie on St. Lazare, gobbling it up on a bench outside the one-time mauseleum of Louis & Marie Antoinette in an intimate park named after the royal couple interred there by the Revolutionaries before the Restorationists moved them to Versailles, arrosing the chicken with red wine under the suspicious eyes of a guardian.

If I headed right on Paradis, I soon arrived at the rue de Faubourg St. Denis and Little India-Pakistan. If instead of turning right at St. Denis as Paradis turned into Fidelité (heading the other direction, one might conclude the inverse) I continued straight to Magenta and on past the Gare de l’Est, I’d end up at the Canal St.-Martin. It was catching a projection of Marcel Carné’s “Hotel du Nord” at a park on the canal across from the current Hotel du Nord in the summer of 2001 that decided me to settle in the 10th, and my little corner of Paradis seemed to be the perfect cockpit for discovering the Paris a lifetime of being weaned on Pissarro, Tintin, Babar, “The Red Balloon,” Madeline, Frere Jacques, Brel, Montand, and Piaf had primed me for. And if my brood didn’t quite tally the dozen kittens who accompanied Michel Simon, his co-pilot, and the co-pilot’s bride when they docked at the canal at the end of a honeymoon traverse of the waters of France in Jean Vigo’s 1934 “L’Atalante,” I at least had three feline co-pilots and felt I was ready to search for the bride.

So there she was, that evening just before Christmas 2001, waiting behind the closed door of the unfinished, dirt-floored bathroom. ‘She’ was Benedicte, a 33-year-old banker (our burgeoning couple thus neatly inverting the Jamesian pair that opens “The American” with the French lass copying a painting at the Louvre and the Yank man asking “How much?”). “I’m not quite ready. I still have to take my shower, and I need to do it here in the kitchen as the salle de bain isn’t finished yet,” I’d announced. I was taking Benedicte to dinner at the La Verre Volé (“The Stolen Glass”), a cozy if snobby ‘cave au vins’ cum bistro on the rue Lancry, which wound from Magenta to the canal – and, with its ‘bio’ wines, an early outpost for the BoBos, or Bourgeoisie Bohemians, who would colonize the canal district over the next 15 years, but which in 2001 still shared the street with barber shops guarded by cigarette-toking Serge Gainsbourg dolls. Ever the banker, Benedicte had arrived punctually, covered in a non-descript jacket and with her dirty blonde hair in a neat bun above her thick librarian’s glasses and big round eyes. “It’s okay, I can wait here in the salle de bain until you’re proper,” she answered. Then, after disappearing into the large bathroom: “It’s kind of the bordel here, non?,” ‘bordel’ translating as ‘brothel’ and meaning ‘chaos.’

When we returned to Paradis from dinner, emboldened by a bottle of bio Beaujolais and romantically juiced by a walk along the fog-shrouded canal, I decided to reverse-engineer Arletty’s imprecation (in “Hotel du Nord”) and create as much “atmosphere” as possible when you’re sitting on a bare thin futon on a weathered grey-blue carpet and still coughing from the dirt in the entry-way by starting up Earth, Wind, and Fire’s “Imagination” on my laptop, posed on the only piece of furniture in the room, a sky-blue formica table I’d found along with matching square stools outside my apartment building in the Cité Falguieres next to the Pasteur Institute, one-time worker housing since converted to bourgeoisie digs. (The rectangular glass-roofed artist atelier at the entrance of the Cité – located in the 15th arrondissement on the peripherie of Montparnasse — had once been inhabited by Chaim Soutine, who spent his sun-infused days dabbing colors on canvasses and his unlit nights dodging fleas parachuting from the ceiling before a Philadelphia art collector named Dr. Barnes rescued him from obscurity.)

So I imagined myself with you. See what imagination can do.

It didn’t take much imagination to decipher the bedroom eyes Benedicte threw at me from behind her goggle-eyed glasses, but she added a hint for the hopelessly dense by briskly undoing her dirty-blonde hair from its Peggy Proper (as Jean-Pierre Leaud’s Antoine described Claude Jade in Truffaut’s “Stolen Kisses”) pony-tail and pulling me down on the futon for my first trip to Paradise on the rue de (Paradis). We grappled hungrily, two mismatched souls whose only real point in common was their desperation for love, escalated quickly to third base and stopped just short of home plate, but I was sated and she seemed content, snuggling her back against me as we fell asleep. In the morning I brought cappuccino poured into my two large brown and white Italian ceramic cappuccino mugs from San Francisco’s Cafe Trieste to the bed, my hands shaking, and promptly spilled it. “Oh la la! You are so nervous! Why do you shake like that?” Benedicte said, rising in just her tee-shirt and panties. “Do you have some white vinegar? That will erase the stain.” But the coffee stains would remain on the drab blue-gray carpet on Paradis for the next six years, long after our aborted relationship had turned to vinegar. As far as “Love on the Run” (to refer to the title of the final Antoine film) goes, I was a marked man.

The apartment at 49, rue de Paradis, several years after we moved in on November 28, 2001. At the time of this chapter, it was empty. Except for the cats: That’s Sonia the Alaskan on the bed, Hopey the San Franciscan on the chair at right, and Mesha the other Alaskan is no doubt looking out at the balcony from the cat window. (See below.) Note mylar ceiling. Photograph copyright and courtesy Christine Chen.

The apartment at 49, rue de Paradis, several years after we moved in on November 28, 2001. At the time of this chapter, it was empty. Except for the cats: That’s Sonia the Alaskan on the bed, Hopey the San Franciscan on the chair at right, and Mesha the other Alaskan is no doubt looking out at the balcony from the cat window. (See below.) Note mylar ceiling. Photograph copyright and courtesy Christine Chen. The balcony (cat window in foreground), with the view towards the rues Poissonniere, Bleue, and Papillon. Turning right at the corner lead eventually to Montmartre. Turning left to the Grands Boulevards. (For more itineraries, see below.) The first complete building across the street is where Corot taught color values to Pissarro and Morisot. Photograph copyright and courtesy Christine Chen.

The balcony (cat window in foreground), with the view towards the rues Poissonniere, Bleue, and Papillon. Turning right at the corner lead eventually to Montmartre. Turning left to the Grands Boulevards. (For more itineraries, see below.) The first complete building across the street is where Corot taught color values to Pissarro and Morisot. Photograph copyright and courtesy Christine Chen. Left: the rue Lafayette, which leads to the Opera House. Right: The view from the balcony down the rue de Paradis, which leads eventually to Fidelite, the rue St.-Denis, the Gares de l’Est et Nord, and the Canal St.-Martin. Photograph copyright and courtesy Christine Chen.

Left: the rue Lafayette, which leads to the Opera House. Right: The view from the balcony down the rue de Paradis, which leads eventually to Fidelite, the rue St.-Denis, the Gares de l’Est et Nord, and the Canal St.-Martin. Photograph copyright and courtesy Christine Chen. Background: The ‘cat perch’ leading to the kitchen. Foreground: A door converted into a book table, where the stars include several of the important women in the author’s life, such as Leonor Fini, Kate Bush, Josephine Baker, Brigitte Bardot, Madeline, and others. Photograph copyright and courtesy Christine Chen.

Background: The ‘cat perch’ leading to the kitchen. Foreground: A door converted into a book table, where the stars include several of the important women in the author’s life, such as Leonor Fini, Kate Bush, Josephine Baker, Brigitte Bardot, Madeline, and others. Photograph copyright and courtesy Christine Chen.