PARIS — From a minister of culture during the precedent administration who famously admitted that she didn’t have time to read books, newly inaugurated president Emmanuel Macron and his freshly-minted prime minister Edouard Philippe, both famous readers and promoters of literature, today took a major step in recuperating the image of a portfolio for years honored by Andre Malraux by naming as the country’s minister of culture and communications Françoise Nyssen, long-time director of Arles-based Actes Sud, one of the crème de la crème of French publishers. Together with Macron’s campaign promise to increase library hours at night and on the week-ends, and Philippe’s record as mayor of Havre in sending bookmobiles around the coastal city, the appointment of Nyssen, who also founded a school focused on listening to the child after the suicide of one of her own children, augurs well.

Category Archives: Bookstores / Libraires

An Important Announcement from The Arts Voyager regarding accessing our stories and art

Starting today, all new Arts Voyager stories and art will be distributed exclusively by e-mail, to subscribers. Subscriptions are just $49/year ($25/year, students and unemployed artists), and include archive access to both the Arts Voyager and the 2,000-article Archives of The Dance Insider, our sister publication. To subscribe, designate your PayPal payment in that amount to paulbenitzak@gmail.com . Or write us to at that address to find out about other payment methods and about paying in Euros or British pounds. If you are already an Arts Voyager or Dance Insider subscriber, you are already signed up. Special Offer: Subscribe before December 15 and receive a second subscription for free — the perfect holiday gift for the Arts Voyager on your list.

November 13, 2015: Frontline, Paris — The year when living became dangerous

(Revised from its initial publication on November 16, 2015, direct from Belleville, Paris. Bataclan was re-opened last night, November 12, in a benefit performance for survivor associations, by Sting, with “How Fragile we are.” In unity, strength. De l’union, la force.)

By Paul Ben-Itzak

Copyright 2015, 2016

“Don’t say a prayer for me now

Save it ’til the morning after.”

— Duran-Duran, reprised by Eagles of Death Metal, performing November 13 at Bataclan, Paris

“We know the children who begin the youth of loss greater than they can dream now.”

— Wendell Berry, “November 26, 1963”

“C’est pas rien, les mots.” (Words are not nothing.) –Antoine Leiris, whose wife was killed at Bataclan on November 13, 2015, author of “You will not have my hate” (Vous n’aurez pas ma haine.), in an interview broadcast November 13, 2016 on France Inter radio.

PARIS — Imagine if, instead of the Twin Towers, Mohammed Attah and his gang (can we stop calling Da’esh the “Islamic State”? It’s like calling the Mafia “The Good Catholics Club”) had struck City Center and instantly killed 90 spectators and held 1400 others hostage, simultaneously mowing down diners at Veselka and four other cafes. This is what happened here Friday night, when the terrorists struck down 89 fans of an American rock band known for reprising a Duran-Duran hit and 41 others at restaurants and cafes in neighboring quarters of the 10th and 11th arrondissements here in the East of Paris, as well as the Stade de France in the suburb of St.-Denis. The massacres, as mayor Anne Hidalgo pointed out Saturday, were hardly random, “It’s the Paris of vivre ensemble (living together) which was attacked.” As it happened, I was in the area Thursday night, first at a group exhibition at the three-floor Bastille Design Center on the Boulevard Richard-Lenoir whose highlight was a display that humanized the migrants by putting their visages on postage stamps (suggesting they could bypass the migratory ordeal by simply mailing themselves to Sanctuary); later returning from the Theatre de la Bastille after seeing Vincent Thomasset’s take on Julien Previeux’s “Lettres de Non-motivation,” which treats the unemployment crisis at the root of Europeans’ most legitimate fears of an influx of migrants in a humorous fashion, with a series of letters responding to job ads in which the correspondent explains why he will not be able to accept the job not yet offered to him. The last time I was at Bataclan was in 2003, covering a demonstration by striking freelance or intermittent artists, protesting proposed reductions in their unemployment compensation. Angry that the private nightclub had not joined other theaters in honoring the strike, they were there to cajole ticket-holders to go home and to good-naturedly try to get the featured pop singer to cancel, chanting, “Michel Jonasz, avec nous!” The theater management ultimately relented, but even if it hadn’t, the protestors would have simply continued their demonstration — without resorting to violence.

All this is how civilized, normal people respond to societal problems. And it’s just this, a society which has set up a civilized system for dealing with disagreements, processing conflicts, and accommodating difference — vivre ensemble, en effet — which Da’esh, in its nihilism, is out to destroy. (A French artist friend commented that the problem is “We are brought up respecting life, and with a fear of dying; they don’t have that fear.” But I think it goes deeper than this: They also don’t see their victims as humans whose lives have any value. Another trait the French — and all civilized people — strive for, at their best, is empathy.)

On a deeper level, what they want to infect the rest of us with by these massacres is a lack of faith, a sense of meaninglessness and hopelessness. Why go out, why see art, why have a drink with your friend on a cafe terrace — why do whatever profiting from life means for you — if you might get killed doing so, for no reason? Initially, I was afraid they’d succeeded with me; I felt numb. I couldn’t even confront that these murderers’ barbaries were no longer happening someplace else (I was not in Paris during the Charlie and kosher super-market killings), but around my neighborhood, on all the streets that are part of my daily routine; two of the cafes, the Little Cambodia and the Carillon, are at the intersection of the rues Bichat and Alibert, which I pass by whenever I walk from Belleville to the Canal Saint-Martin. Two others – including le Bon Biere, a nondescript brasserie where the Mexican-American college student Noemie Gonzalez was killed – face each other on a catty corner near my treasured Canal St.-Martin, on the street that leads up to Belleville, the rue de Temple. I’ve strolled along the Boulevard Richard-Lenoir heading up from that spot on the canal for 15 years, perusing antique fairs or en route to the Theatre de la Bastille, but also because this street — where Simenon’s fictional Commissaire Maigret ‘lived’ — is part of the Paris myth for me. (Maigret, who was never just interested in finding the culpable, but in understanding his psychology — the reasons he killed, even though they were not reasonable — would be stymied by this particular case and might not even want to probe the mental morass of these terrorists.) It’s at the boulevard Richard-Lenoir where the Canal goes underground, resurfacing at the Arsenal of the Bastille before connecting to the Seine. (Before these recent attacks, the closest I’d ever come in Paris to taking my life in my hands was walking across the narrow lock separating the two fleuves. Today it feels like my life is no longer my own.)

It’s this beauty which these Obscurantists (even that term today seems feeble, because it sounds like someone just turning out a light, and masks the carnage, the ‘body parts everywhere’ evoked by witnesses, which these devils wreaked) are after, and it’s this beauty which finally broke my numbness when, Sunday morning, I walked up to and through the parc Belleville. First it was, simply and literally, the light: The late morning brilliance of the Sun reflecting off the multi-colored autumnal leaves. Then, when I reached the belvedere, it was looking out on the Eiffel Tower and other landmarks – and light-houses(phares) — of ‘les Lumieres’ like the Pompidou Museum of Modern Art as well as the Pantheon, where are enterred artists like Zola and Hugo who confronted societal problems not with swords but minds, as well as Marie Curie, who cured diseases and, most recently admitted, resistants to the Nazi Occupation. But more immediately, in the park which descends several city blocks of this neighborhood in which Chinese, Arab, African, and even some American and English immigrants live together along with artists and BoBos (bourgeoise Bohemians), you see the plaza beneath and descending from that, a rectangular fountain, terminating in a circle, drained for the Fall. Spotting a man leading about a dozen students in Tai Chi or Tai Kwon Do exercises and demonstrating combat ‘rules,’ I thought: No more rules. But then hearing and seeing children of all colors playing, laughing, and yelling, I finally lost it and started to cry. First, because of their blissful ignorance. A week ahead of November 21, I thought of Wendell Berry’s “November 26, 1963,” a tattered copy of the book of which, illustrated by Ben Shahn and given to me on my third birthday, I still retain, the words, “We know the children who begin the youth of loss greater than they can dream now” even more potentially prophetic now than they were after President Kennedy’s assassination. (Also prophetic was the inscription of the family friend who gave it to me: “Who can understand the minds of men” who commit acts like this.) And I cried because Paris, or the idea and ideal of Paris — beauty, thought and reflection, art, and, yes, even the sometimes (verbally) violent, or vigorous confrontation of ideas — this is what Paris represents not just to Parisians but the world. When one child announced to his father, “Well, at least it’s sunny,” I didn’t know whether to be re-assured or discouraged that this was all the boy had the right to expect, to be content with.

These days, and like everywhere, Paris can also represent polemic and political recuperation. (Without yet monitoring the response of politicians in the U.S. — in whch I exclude Barack Obama, whose solidarity has been exemplary and without political connivance — I assume some of this recuperation is already going on among right-wing politicians in the U.S.) In 2003, marching here against the U.S.-lead invasion of Iraq (one of whose consequences was the firing of the Bathe officers of Saddam’s army many of whom now make up the cadres of Da’esh; I am really trying to avoid any polemics in this piece, but as an American writing in part for a French audience, I think it’s important to take some responsibility and own up that this is not just a “European” crisis), I was unnerved when, at one of the marches, a group wearing armbands from one of the unions muscled us out of the way so they could get to the front of the march, as I was by the various banners advertising political parties and other unions.

So it was that I was heartened on returning to the top of the parc Belleville Sunday evening to watch the Sun setting over the Eiffel. When I first noticed the larger than usual crowd I thought it was another food distribution organized by an association that supports Balkan immigrants. But no, it was just ordinary Parisians, and — judging by the different languages — tourists gathering. Not an organized demonstration of solidarity, no signs, and no political recuperations. Just people like me who felt the need not to watch television replays and endless if well-meaning coverage, but just to be reminded of what we’re here for, of the things they can’t kill — and to search for this solidarity, this fellowship in Paris’s most cosmopolitan of neighborhoods. As I leaned against one of the railings looking out at the purple and gold deepening sky (“Look, there’s even green!” one boy said to his father) setting over the Eiffel, I heard and saw next to me an elegant young French man with a Johnny Depp van dyke, long hair, and top-hat speaking with a young blonde Dutch woman — in English. When he opened up his aluminum thermos and poured a couple of cups of something hot, I opened mine and, after filling my plastic cup with fresh mint tea, lifted it to them and proposed, “Tchin.” “Santé, Monsieur,” the man answered steadily. “We need it especially now.”

We also need artists. The government will strike back against these murderers, as they should. They will institute more protection measures, which should strike the proverbial balance between protecting our lives and the values which Da’esh is trying to kill. (I think President Francois Hollande gets this, announcing succinctly that it’s our freedom they’re after.) But we will also depend on artists to defy these Obscurantists, these worshippers at the shrine of death — and after this attack on a theater, for both artists and audience, continuing to create art and patronize the arts is a form of defiance — and keep reminding us of what we’re fighting for: culture, light, the right to debate, the prism art offers us and which is not always one-dimensional….

And we will depend on artists to help us remember to laugh, even at the problems society is faced with. In this context, Vincent Thomasset’s dramatization — and physicalization — of Julien Previeux’s book “Lettres de Non-motivation,” compiled of his responses to real job announcements in which he informs the employer why he will, unfortunately, be unable to take the position (not yet offered him), is an acid take on the bitter situation in which so many find themselves today, chiefly applying for jobs with employers who rarely bother to respond any more, or who reply with form letters. This last fact is born out immediately by the large proportion of prospective employers — their help wanted ads variously projected on a compact upstage screen or read out loud by the actors or pre-recorded — who reply to the often sarcastic ‘Lettres of non-engagement’ with notes saying, essentially, We regret but despite your high qualifications, we are unable to offer you the job. In other words, form letters which reveal the disdain so many employers have for the out of work.

If one of the challenges Thomasset, also a choreographer, set himself was that of theatricalizing a literary albeit humorous work, he mostly succeeded, largely thanks to the diverse talents of his five-person cast. In the most original response, Johann Cuny informs a company advertising for a high-tech position that he is writing them from the year 2065, where unemployment is at 78 percent, and where consequently a whole separate unemployment office has been created to find jobs in the past, thanks to a time transporter, before concluding that as the machine is malfunctioning and the time transporter repair-man is stuck in 1962, he will be unable to accept the job. As he recites his more or less straight response, the multi-talented dynamo known as Michele Gurtner, standing next to him, makes clickety-clackety sounds accompanied by robotic arm movements, indicating that this is the way people talk in the future. Later, Gurtner only slightly shifts gears to reply to another ad as if she is an android made to please. This powerhouse performer then again alters her dramatic tempo to deliver an employer’s (real) formulaic response a la Sarah Bernhardt, by the end rendering the traditional French business closing “I assure you of my sentiments the most distinguished” as if it’s the culmination of a tragic drama, breaking down in tears and collapsing over Cuny, who had earlier delivered the non-engagement letter she’s responding to.

The teaser comes with the cloying, husky-voiced Anne Steffans’s ebulliently danced response (mimicking a cheerleader routine) describing the letter she wrote about how perfect she is for the given position and how she’d love to take it — before announcing that when she woke up in the morning the letter had disappeared and “perhaps it will get to you under someone else’s signature,” a line taken up as a choral refrain by the rest of the cast (also including David Arribe) before “Lettres of Non-engagement” ends, as it must, with the stoic bearded Francis Lewyllie reciting the ultimate of non-engagement letters, as might Melville’s Bartleby (inscribed in the minds of school-children here as in the U.S.), enumerating why he’d prefer not to do all the tasks required by the job.

Unfortunately, as of Friday, November 13, “Je prefere pas” — to go out to the theater, regale on the terrace of a cafe — has become a tempting option. “I prefer not” to be *engaged* — in the French sense of the word (which means ‘committed’), less.

“Lettres of Non-engagement,” co-produced by the Theatre de la Bastille, the Festival d’Automne, and several other presenters around France, continues through November 21 at the Theatre de la Bastille, in the Bastille, where Parisians will, defiantly, continue laughing and arguing on the many café terraces —parce qu’il faut continué.

Cross-Country, a Memoir of France, 20: The Man with the Child in his Eyes

“So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.” – F. Scott Fitzgerald, “The Great Gatsby”

“He’s here again: The man with the child in his eyes.” – Kate Bush

By & Copyright 2016 Paul Ben-Itzak

(Like what you’re reading? Please support the Arts Voyager by donating through PayPal, designating your payment to paulbenitzak@gmail.com, or write us at that address if you prefer to pay by check or in Euros. Based in the Dordogne and Paris, the Arts Voyager is also currently looking for lodging in Paris. Paul is also available for translating, editing, Djing, and webmastering assignments.)

In an old house in Paris, les paradises reel

“She loves books,” I insisted, struggling to get Pierre’s attention. “She’s serious. She’s got eyes to die for. She appreciates that I’m a writer.”

Briskly shelving cellophane-sealed histories of art and philosophy, squeezing dust-covered profiles of anarchist agitators and existential theorists in between musty biographies of Belle Epoch clowns and Front Populaire officials, carrying whole rows of obscure scientific revues from the balustrade overlooking the Seine lapping at the banks of the Ile St. Louis across the way — where Gauthier and Baudelaire once threw lavish hashish parties and Camille Claudel plummeted into “the years of darkness” — to his three bruised dark green metal stalls, occasionally brushing his long stringy pony-tailed graying brown hair away from his John Lennon glasses or flicking the soot off the sleeves of his Tang-colored jumpsuit, not even taking time to glance at the fathomless river rippling under the reflections of the crepuscular Sun, Pierre didn’t seem to be listening to my rapturous account of my first dinner date with Emilie, who I’d met at his 40th birthday fete near the Place Edith Piaf.

In Henry James’s “The Ambassadors,” Lambert Strether takes a break from trying to rescue a friend’s errant son from the jaws of a man-eating Parisienne to troll for literary treasures in the bookstands lining both banks of the Seine, finally scoring a complete volume of the works of Victor Hugo, poet-champion of les miserables and exiled political opponent of Napoleon III whose anguished militating against the death penalty from an island in the English Channel stretched even across the Atlantic to plead mercy for the abolitionist John Brown. If it’s true that, as pointed out by Robert Badinter – who as Mitterand’s attorney general would fulfill Hugo’s dream of decapitating the guillotine a century after his death – France is not so much the country of the Rights of Man as the country which declared the Rights of Man, it was Hugo picking up the mantle of Voltaire before passing it on to Zola who would try to ford the abyss between the declarations and the deeds. The gap between the piss-poor metier of bouquiniste – Pierre’s — and that of published author, by contrast, had frequently been bridged. Michel Ragon, the most cultivated man alive in France today (as of this writing, in late 2016), got his start as a bouquiniste before becoming the country’s premiere critic of art and architecture in the second half of the 20th century, as a side oeuvre keeping a log of proletarian movements that culminated in “La Memoir des Vaincus” (the memoir of the vanquished) the loosely fictional biography of a sort of Zelig among the anarchists or, more specifically, anarcho-syndicalists (anarchist labor organizers). (There’s a strain of anarchism in even the most encadred of French souls; as I write this, French policemen and women – the very embodiment of State order — are defying both their government and their unions by marching for more modern means and the right to shoot in self-defense.) Léo Malet – who was baptized by the anarchists and accompanied the surrealists before inventing Nestor Burma, the down-at-the-mouth French answer to Philip Marlowe, a poor man’s Maigret unafraid to dive into the muck of the Seine to catch a bad guy, whose rich vernacular and poetic vocabulary make Simenon look like Hergé and who left a trail of bodies in each of the 15 arrondissements in which his New Mysteries of Paris were set — was rewarded for this fidelity to the city with a bouquiniste’s concession, only to give it up after a few months because “I preferred reading the books to selling them.” And when another Léo, Carax – the bad boy of French cinema – wanted to demonstrate how far off the deep end the hero of his 1986 “Mauvaise Sang” had plunged after agreeing to steal a sample of HIV-contaminated blood with Juliette Binoche and Michel Piccoli, he had him break into a bouquiniste’s box after roaming the fog-addled bridges of the Seine in a midnight delirium. It was about the most fragile target one could pick; Pierre supported his metier de coeur by working part-time as a museum security guard, further trimming his expenses by jumping Metro turn styles.

So when I bought my first art book from Pierre, a tome on Impressionism published in the 1950s (the ideal epoch for the quality of the reproductions) with a portrait of Berthe Morisot as painted by her brother-in-law Manet on the cover, it was as if I had procured a part of Paris history directly from one of its guardians, another way to insert myself into the city’s lore.

Finally padlocking the last of the rusty boxes and starting off at a clipped pace for “Le chope des compagnons,” the bar across the street from his stand and the Hotel de la Ville, where he’d promised to introduce me to an Italian mason who specialized in tombstones (my dance magazine wanted to restore what at that juncture we still believed was the ballerina Taglioni’s dilapidated grave in the Montmartre cemetery, only to learn later from Edgar Allen Poe that the mother of pointe was actually buried in the Pere Lachaise sepulcher of the Bonapartiste ex-husband who’d barred her from the domicile congugale when she refused to stop dancing), Pierre scoffed, “Ecoute, it’s not you she’s interested in. She’s a little girl from the provinces set loose in Paris. For her you’re the American — you’re exotique. If it doesn’t cost you anything, pourquoi pas? Mais fait gaffe: Already she’s taking advantage of Marcel.” Marcel was the fellow bouquiniste who’d been putting Emilie up since she’d debarqued from Toulouse. “She was supposed to stay for a week-end, already she’s been there for three weeks. He has a thing for her, and she’s abusing his kindness.” As with his attempts to debunk the authenticity of Sarah Bernhardt’s ornate personal mirror, which I’d recently purchased from a Bohemian couple at a Montmartre garage sale, Pierre seemed bent on denying the legitimacy of my burgeoning French connections, be they anchored in the past or present. For me however it was clear that his skepticism derived from too many years of seeing tourists leaf through his precious books – the cellophane wrappers were meant to discourage such marauding — without buying anything, while he paid his rent watching the same Philistines photograph themselves in front of the museum masterpieces he guarded.

“She’s pretty helpless, Pierre. She needs a friend. And as for taking advantage of Marcel, it’s not her fault if she can’t find work. She’s a social worker with ado’s at a time when the government has just cut 8,000 aide jobs from the schools.”

“Okay, Candide! Fait comme tu veut. Just don’t come crying to me afterwards. The problem with you Americans is you’re too romantic about France. You think every waif you encounter wandering the quays has just stepped out of the pages of Les Miserables, is harboring the soul of Piaf, and is looking for a Marcel Cedran to protect her. And you don’t even like boxing.”

“Dans une vieux maison a Paree

Ont vecu 12 petites filles

dans deux etroite files.”

“Filles,” (sniff), “doesn’t rhyme with files,” Emilie pointed out with nasally muted contentiousness before taking a sip of chicken soup with approximated matzo balls. Unable to find Manischevitz, I’d bought a box of matzo crackers (or pain d’azyme) imported from Oran — the Algerian city on a hill in which Camus had set “The Plague,” which hosted a large Jewish colony — and pulverized them to compose the body of the balls, pulling out the major gourmet artillery to lure Emilie to my petite coin de Paradis on the rue de Paradis when she’d wanted to cancel our rendez-vous, pleading an incipient cold. “I’ll make you a big pot of hot chicken soup with matzo balls.”

“Qu’est-ce que c’est?”

“It’s like Jewish penicillin.”

“You see? It’s like I told you, your Jewish genes are trés important to you.”

“It has nothing to do with my Jewish genes,” I insisted. “It’s my California roots. My father built one of the first Nouveau California Cuisine restaurants in San Francisco, and my mother did the cooking. The only difference is her matzo balls were made of whole wheat.”

“Pourquoi pas tofu?”

“She was Old School Nouveau California Cuisine.”

“If I drink the soup, it will make me Jewish?” French humour often being more refined than American, I never knew whether Emilie was kidding.

“It won’t make you Jewish, but it might make you less blueish.” Getting no response – the “Yellow Submarine” film reference escaping her, or maybe she just didn’t get my own sense of humour – I added, “It might help your cold.”

Emilie was now perched primly on the futon with her delicate fingers clasped between her knees, looking thinner in a somber brown skirt over black tights, a light-weight tan pullover not helping her ghostly, wan pallor. In an effort to rally her spirits – the soup had only increased the sniffling, and I was having trouble charming her — I’d pulled out my Madeline omnibus. Ludwig Bemelmans’s Madeline – the hero of a series of children’s stories set in Paris which no one in France has ever heard of, just as many have never heard of “The Red Balloon” — had been the obsession of Mimi Kitagawa, my childhood best friend who’d turned over in her crib on Liberty Street in San Francisco in 1964 at the age of three and a half and breathed her last breath. During a desperate late-night passage in Greenwich Village in 1997, reeling from a push-and-pull, now I love you, now I don’t relationship with an exotic modern dancer-contortionist and meandering up Broadway in search of salvation, I’d ended up at the Strand (“8 miles of books, millions of bargains”), where a copy of the Madeline collection had beckoned to me from a display shelf near the ceiling, which I took as a hail-Mary from Mimi, by then my guardian angel. Later, whenever the ameritune of past experience threatened to blind me to present possibilities, I’d try to let Mimi become the child taking over my perspective (in Californese: “I’d channel her”), and remind myself that I had a responsibility to live my life for two.

I was now (we’re back on the rue de Paradis, in October 2004) attempting to translate the first Madeline tale into French to make it legible for Emilie, or at least get a rise out of her with my maladroit bungling.

“Filles,” Emilie was pointing out, “Is pronounced ‘fee’; files,” French for ‘lines,’ “is pronounced ‘feeel.’ So in fact, Monsieur Paul” – she looked up from the book to emphasize the point with her eyes – “they do not rhyme.” Seeing my deflated disappointment – and realizing I was doing my valiant best to distract her from the cold — she added, this time with a slight upturn to her lips and an accompanying humour in her eyes to indicate she was being ironic, “Et pour ma part, je commence a perdre le file,” the latter phrase meaning ‘lose the thread.’

“Dans deux FEEEEEEEEEEEL etroites donc, ils ont coupé leur pain,” or broke their bread, I continued, “et ont lavé leurs teeth,” which I emphasized by pointing to Bemelmans’s simple sketch of the 12 girls aligned on either side of the orphanage dinner table brushing their teeth, “avant de se mis au LITH,” I concluded, adding the lisp to “lit,” the French word for ‘bed,’ to get the rhyme with ‘teeth.’

Turning the page to a double-spread demonstrating the girls’ attitudes towards, respectively, the forces of good and those of evil, I translated “They smiled before the good” as “Devant le bon, ils se sont rejoui” to get the rhyme with my translation of “and frowned on the bad“: “Tandis que devant le mal, ils aviez que du mepris.”

“Pas mal,” Emilie admitted, finally smiling through the sniffles. “But I don’t understand why for the good he draws a picture of a rich woman feeding a carousel horse in front of les Invalides – “

“Maybe it’s Napoleon’s horse?” I offered feebly, Bonaparte’s ashes being stored at the army museum.

“And maybe you lead me to Waterloo! Et apres?”

I continued reading and translating until the page on which Madeline, after an emergency appendectomy, wakes up in a hospital room full of flowers.

Putting her thin fore-finger on one of the pictured vases, Emilie complained, “She gets all those flowers for her appendix, and you have nothing for me?”

“Au contraire! So, my belle-mere has a boutique in San Francisco where she sells exotic soaps, shampoos, bubble-baths, and body oils. It’s actually how she and my father met; her store was across the street from his restaurant.”

“Ah bon?” This had spiked her interest, as I’d cleverly maneuvered food, perfume, and romantic rendez-vous into the same sentence.

“My step-mom – er, belle-mere – actually has a French last name. So you could say I’m part French.”

She smiled, if just with her eyes.

“Anyway, I have something she sent me that I want to give you.” Even though I’d asked my step-mom to send me the wild rose body oil specifically for such an occasion, I was trying to casualize the gift so as to not scare Emilie away. Normally I’d pretend to pull such small packages out of my victim’s ear, but the last time I’d tried that trick (inherited from my grandpa in Miami Beach, a liquor salesman, who used to do it with pennies or his wide gold ring with the oval black stone), the recipient had shrieked, thinking I was plucking a bee out of her bonnet, dissipating the ambiance. So this time I merely pulled the present, enveloped in bubble-wrap, out of my pocket.

“It’s very sweet of you,” Emilie said after twisting the cap off the miniscule glass tube and taking a whiff, patting and looking down at my hand to avoid looking me in the eyes. “If you don’t mind I will save it for later, because it could make me sick if I put it on now with my cold.”

“Speaking of roses,” I said, jumping to the stereo to cue “La Vie en Rose,” “Would Mademoiselle care to dance?” Looking up noncommittally at my offered hand, which at that moment felt to me like a gorilla’s, she tentatively placed her downy palm in mine and rose with an effort. In theory, waltzing with a French girl to Piaf singing “La Vie en Rose” in my own Paris apartment on the rue de Paradis across the street from where Pissarro and Morisot learned to paint from Corot should have felt like a dream fulfilled, but my predominant sensation as I strained my back over Emilie’s doll-like hunched shoulders was the memory of dancing with Jocelyn Benford at the Lowell High School 1976 sophomore dance (“I need someone to ride the bus home with,” Jocelyn had explained, counting on my junior high crush still lingering), our ersatz silk shirts sticking sweatily together, broken up only by the ridged outline of Jocelyn’s bra, as we rotated to Earth Wind & Fire singing “Reasons.” As this French girl and I spun slowly on Paradis, the rose light-bulb I’d switched on coronating the reflection of our faces in Sarah Bernhardt’s abalone encrusted beveled mirror with a velvet aureole, Emilie felt even more fragile and fleeting in my American grizzly-bear grasp than that long ago 14-year-old.

Cimetière avec vu sur mer

“In the suburbs of Algiers, there is a little cemetery with black iron gates. If you go to the far end, you look out over the valley with the sea in the distance. You can spend a long time dreaming before this offering that sighs with the sea. But when you retrace your steps, you find a slab that says ‘Eternal regrets’ on an abandoned grave. Fortunately, there are idealists to tidy things up.”

— Albert Camus, “L’Envers et l’Endroit,” 1937. Published in “Lyrical and Critical Essays,” edited by Philip Thody and translated by Ellen Conroy Kennedy. Copyright 1968, Alfred A. Konpf, Inc., Copyright 1967 by Hamish Hamilton Ltd., and Alfred A. Knopf.

Protected: Nous les filles artistes de Ménilmontant (Illustrated)

The ink that dreams are made of, 2: Krazy like a Kat

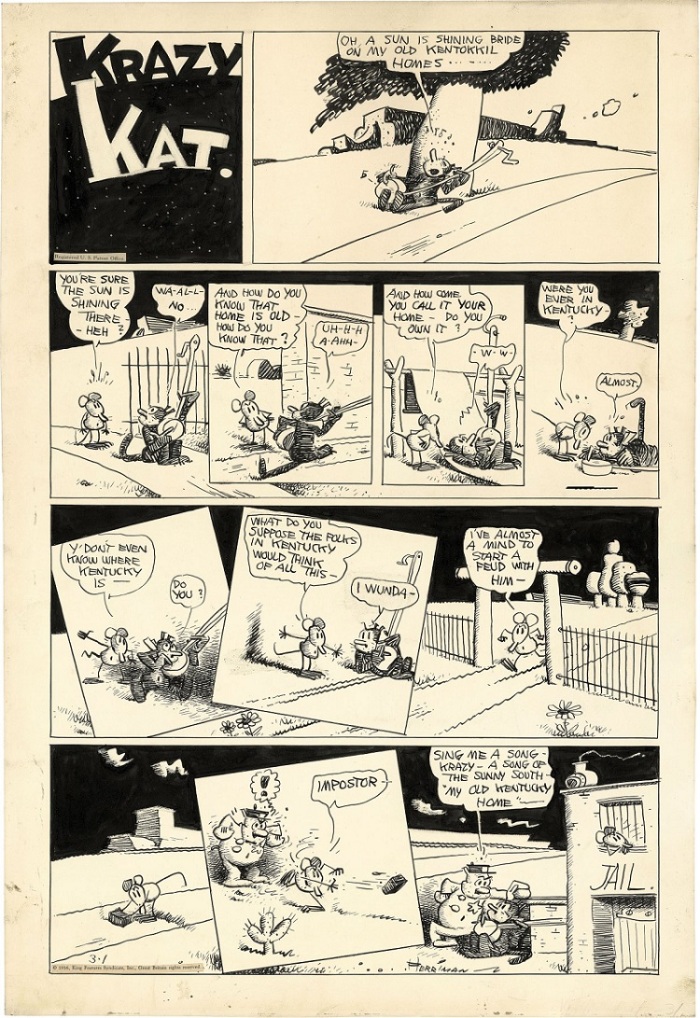

George Herriman, “Krazy Kat, My Old Kentucky Home.” India ink on Bristol board, 24 x 16 1/2 inches. Original drawing for a Sunday comic strip featuring Krazy Kat published in 1936 by King Features Syndicate. Signed. Artcurial pre-sale estimate: $40,000 – 50,000. Image copyright and courtesy Artcurial.

George Herriman, “Krazy Kat, My Old Kentucky Home.” India ink on Bristol board, 24 x 16 1/2 inches. Original drawing for a Sunday comic strip featuring Krazy Kat published in 1936 by King Features Syndicate. Signed. Artcurial pre-sale estimate: $40,000 – 50,000. Image copyright and courtesy Artcurial.

By Paul Ben-Itzak

Text copyright 2016 Paul Ben-Itzak

(Like what you’re reading? Please support the Arts Voyager by donating through PayPal, designating your payment to paulbenitzak@gmail.com, or write us at that address if you prefer to pay by check or in Euros. Based in the Dordogne and Paris, the Arts Voyager is also currently looking for lodging in Paris, Bordeaux, or Lyon. Paul Ben-Itzak is also available for translating, editing, and webmastering assignments.)

Before it was an auction house, Artcurial was an opulently furnished gallery of contemporary art, its 2500 square meter home lavishly underwritten by no less than l’Oreal and opening with a bang with permanent exhibitions featuring the likes of Bonnard, Atlan, Braque, and Poliakoff. Kandinsky’s “Music Salon,” created in Berlin in 1931, was reconstituted, monographs were published on the side for the likes of Wilfredo Lam and Salvador Dali, and le tout was augmented by what Opus International’s Jean-Louis Pradel described after the opening as “one of the richest contemporary art libraries to be found in Paris, [with] 4000 books on 20th-century art and more than a hundred international art revues.” All this was trumpeted on the gallery’s 1975 opening with a massive advertising campaign which broke with the traditional reserve of the toney neighbor galleries on the august rue Matignon. Counter-intuitively — because one would assume that the content of an auction is determined primarily by who’s decided to sell what — this curatorial instinct seems to have been retained in Artcurial’s auctions. Its second Hong Kong sale — to be held Monday in… a museum — is no exception. Notwithstanding company official Isabelle Bresset’s vaunting the sale of 80 examples of street and comics art as representing “a vibrant panorama of a part of *contemporary art* (emphasis added),” among the catalog of 80 lots are two original drawings which also fulfill the historical-educational function of a museum. In addition to a strip by Little Nemo father Winsor McKay, George Herriman’s Krazy Kat also shows up. If the original drawing in question, dating from 1936, doesn’t boast the surrealist mesas and arroyos of Herriman’s work from the 1920s, the three principal characters (see above) are in fine form and the landscape is still peopled by a cactus, a cluster of giant toadstools, and what could be a range of Arizona pyramids. (Source for background on Artcurial gallery: Jean-Louis Pradel, “Artcurial,” Opus International, February 1976.)

Looking through the eye of Baudelaire

Honoré Daumier (1808-1879), “Le palais de justice,” 1850. Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, Petit Palais. © Petit Palais / Roger-Viollet. “The Caricature wages war on the government,” Baudelier wrote. “Daumier plays an important role in this permanent skirmish.”

Honoré Daumier (1808-1879), “Le palais de justice,” 1850. Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, Petit Palais. © Petit Palais / Roger-Viollet. “The Caricature wages war on the government,” Baudelier wrote. “Daumier plays an important role in this permanent skirmish.”

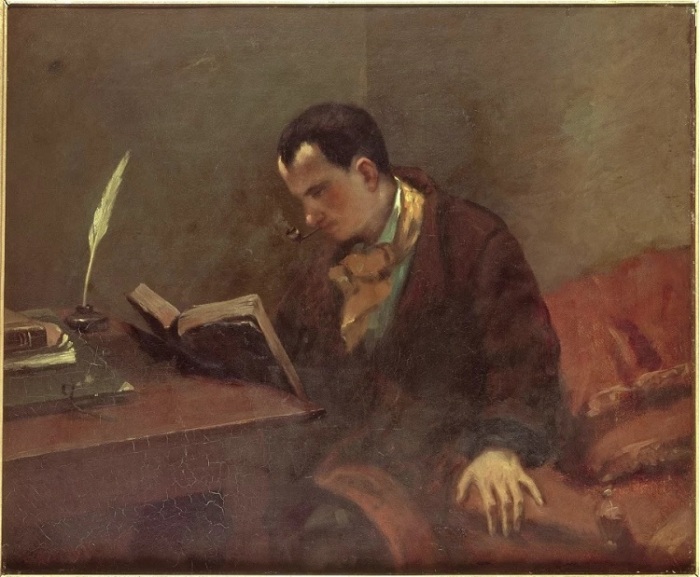

Gustave Courbet (1819 – 1877), “Portrait de Baudelaire,” 1848. Montpellier, musée Fabre. Photo © RMN Grand Palais / Agence Bulloz. When Baudelaire co-founded the ephemeral journal “La Salut Public” in 1848 — it lasted just two issues — it was Courbet who furnished the frontispiece.

Gustave Courbet (1819 – 1877), “Portrait de Baudelaire,” 1848. Montpellier, musée Fabre. Photo © RMN Grand Palais / Agence Bulloz. When Baudelaire co-founded the ephemeral journal “La Salut Public” in 1848 — it lasted just two issues — it was Courbet who furnished the frontispiece.

By Paul Ben-Itzak

Copyright 2016 Paul Ben-Itzak

(Like what you’re reading? Please support the Arts Voyager by donating through PayPal, designating your payment to paulbenitzak@gmail.com, or write us at that address if you prefer to pay by check or in Euros. Based in the Dordogne and Paris, the Arts Voyager is also currently looking for lodging in Paris, Bordeaux, or Lyon. Paul Ben-Itzak is also available for translating, editing, and webmastering assignments.)

In a proposed addition to the preface of the third edition of “Les Fleurs du Mal,” published posthumously, Charles Baudelaire wrote: “If there’s any glory in not being understood, or in being barely understood, I can say in all modesty that, via this little book, I’ve acquired and merited it in one single blow. Offered many times in succession to a series of diverse publishers all of whom pushed it away in horror, pursued and mutilated, in 1857, following an incredibly bizarre misunderstanding, slowly renewed, enlarged, and fortified during some years of silence, vanished once more, this discordant product of the ‘muse des derniers jours,’ once more brightened up by some new violent touches, dares confront, grace of my insouciance, the bright light of stupidity. Don’t blame me; it’s the fault of an insistant publisher who thinks he’s strong enough to brave the disgust of the public. ‘This book will remain all your life like a blemish,’ one of my friends, a grand poet, predicted from the outset. In effect, all my misadventures have, up through now, proven him right.” But the poet not only subjected his own oeuvre to the light of the often ignorant public, critics, and government censors; he also tried to enlighten the public, as one of the premiere critics of Modern Art, helping to define the shape of the discourse along with his fellow Romantic Theophile Gautier (to whom “Les Fleurs du Mal” is dedicated). Retracing the line of this ‘aesthetic curiosity’ — with frequent links to specific critical texts by the author — is the focus of L’oeil de Baudelaire, an exhibition running through January 20 at the Musée de la Vie romantique in Paris to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Baudelaire’s death. Among the works exposed — many bridging the Romantic and Impressionist epochs — are paintings, sculptures, and prints by Corot, Manet, Delacroix, Octave Tasseart, and, above, Courbet and Daumier. (Source for citation: Charles Baudelaire, “Les Fleurs du Mal,” texte de la Seconde Edition suivi des pieces supprimées en 1857 et des addditions de 1868. Edition Critique établie par Jacques Crépet et Georges Blin. Librairie Jose Corti, Paris, 1942.)

Cross Country / A Memoir of France, 16: An American Protester in Paris

By Paul Ben-Itzak

Copyright 2012, 2016 Paul Ben-Itzak

“I often go to Paris to live yesterday tomorrow.”

— Malcolm McLaren, “Paris.”

“Alors, tu fait l’opposition de l’exterior, c’est bien ca?” I had just told the petite, dirty-blonde, 30-something lawyer with the impertinent blue eyes and girlish voice in the floppy gray trench-coat that I was not even tempted to go back to the U.S. as long as George Bush was president. We were at the sable-colored mosaic “zinc,” or counter, of le Valmy, my ‘café d’habitude’ on the Quai Valmy of the Canal Saint-Martin (I was stationed on the corner stool, from which I could look out at the canal through the Sun-streaked cracked window), a mythic Parisian water-way which runs all the way to the Bastille (diving under a panhandle at the Boulevard Richard Lenoir, where Simenon’s Commissar Maigret ‘lived’ with his doting wife), immortalized in films like Jean Vigo’s 1934 “L’Atalante,” in which Michel Simon’s crusty sea captain takes his first mate and the mate’s bride on a honeymoon tour of France’s water-ways; Marcel Carné’s 1947 fairy-tale “Les portes de la nuit,” in which Yves Montand made his debut (introducing “The Dead Leaves,” neutered in the American version to “Autumn Leaves”) as a man who misses the last Metro to live an oneric night in Barbes (in now mostly Arabic lower Montmartre) which ends with the body of his lover (Simone Signoret) being fished out of the canal; and “Hotel du Nord,” also by Carné, in which the legendary music hall chanteuse Arletty indignantly scolds a paramour in her high-pitched voice, “’Atmosphere!?’ ‘Atmosphere!?’ Is that all I am to you?!” It’s a canal intersected by locks, and even on the increasingly frenetic Right Bank of Paris, pedestrians still make time to stop if they happened to find themselves on one of its bridges (from which “Amelie” liberated her goldfish) when a ferry is about to pass under.

When I returned to Paris to live in the fall of 2001, the canal was being dredged and drained; no dead bodies, but a lot of garbage. While my flat on the rue de Paradis was on the periphery of the 10eme arrondissement which included the canal, it was still a vigorous morning walk past the Gare de l’Est to le Valmy to take my morning noisette, the poor man’s cafe créme, a petite café topped off with a dollop of steaming milk foam. Or if had a few sous to spare, I’d order mint tea served in its own individual silver tea pot, a la Montpellieroise, with a dollop of pine nuts. I’d first acquired a taste for mint tea served this way my second summer covering the dance festival in Montpellier, where a tall French-Arab vendor in a wide-brimmed straw hat and Hawaiian shirt hawked it outside an all-night gnawa party in a medieval cloister, a dance party under gossamer silk canopies where I’d brushed against a materialization of the elusive femme de ma vie, a Moroccon dancer I’d named Fatima, after the anima in Paulo Coelho’s “The Alchemist.” The mint tea had become my madeleine, its murky waters conjuring Fatima’s piercing stare daring me to talk to her, the pine nuts providing the venemous chew of regret that I hadn’t.

I’d earlier tried a bar called “l’Atmosphere,” across the canal from the Hotel du Nord, but ruled it out when I realized it was primarily a gay hang-out; little prospect to find the femme de ma vie there. I was drawn to le Valmy by the sign advertising a weekly poetry slam, which promised an air of San Francisco in Paris, and the exotic music mix. “Who’s the DJ?” I’d asked the thin curly haired French-Algerian 30-something man with the amused grin behind the counter on my first visit. “C’est moi!” Ta’ar owned le Valmy with his prematurely balding brother Maclouf (Max), whose expression also suggested that no matter how grave it seemed, you shouldn’t take it seriously. Unlike Cafe Prune further down the canal towards the Bastille, le Valmy, with paintings or photographs by local artists decorating its dark mustard plaster walls, always well illumined from the tall windows on both sides of its corner location, was hip without being branché – with locals dominating the morning coffee customers — and the tone set by Ta’ar and Max, the staff hip without being aloof. The waitresses were chic yet approachable, French hippy children, and the morning barman, Djamel, a handsome, dark-skinned 40-year-old whose tightly clipped hair and joie de vie made him seem closer to 30, was engaging, funny, and earnestly solicitous, all of which meant there were always lots of vivacious women hovering over the zinc. (Paris tip #145: When looking to meet women, you actually want a bar hosted by an alluring barman, not a mignon barwoman.) We’d developed an easy repartée, but our mutual comprehension was often challenged by the noisy espresso machine and music, not to mention the other conversations, given my still tentative French. (I’d usually go over potential sentences and jokes on my way to the bar each morning.)

Perhaps it was that Ta’ar, Max, and Djamel were French Arabs that made le Valmy the perfect QG (headquarters) for flaunting my opposition to the daily butchering of innocent Iraqis by my country during that spring of 2003. (Yes, it took the spilling of blood to finally bridge the gap between me and the French.) Every morning I would open up Libé, as Parisians refer to the daily Liberation (founded by Sartre and others after the May 1968 student-worker revolts) to the graphic coverage of the atrocities we were perpetrating and visibly shake my head in disgust and dismay while looking at the pictures of dead Arabs. (As American media, from the New York Times to National Public Radio, had helped lead us into this fictional war by their unquestioning, supine acceptance of the Bush-Cheney propaganda, I also felt it was my duty to report back to the readers of my magazine, The Dance Insider, on the quite different reality being reported ungarnished by French media.) At the first Paris protest demonstration in February 2003, shortly before Bush-Cheney abetted by the Times launched the invasion, I’d actually scolded a Communist on the boulevard Montparnasse who’d unfurled a banner equating the American flag with the Nazi swastika, “You wouldn’t be here if not for my country!!” But as soon as we invaded, at the first large demonstration, as we gathered at the Place Concord across the street from the American Embassy, I’d immediately latched on to a group called Americans Against the War. It seemed vital to show that not all Americans were war-mongers out to shed innocent Arab blood. Eventually our group made the cover of Humanité, the Communist daily founded by Jean Jaures, helping to hoist a banner calling for George Bush to be tried for war crimes. (Even if one could only see the back of my head, as I had turned around to help lead the chanting.)

Notwithstanding that I grew up in San Francisco in the 1960s, where I was weaned at the marches against the Vietnam War — when I was five years old I remember a demonstration where my mom pointed at a man in a plaid shirt and said he was probably an undercover FBI agent — I was never an automatic joiner. In fact, growing up among professional protesters in San Francisco gave me an aversion to rote rabble-rousing. I only demonstrated when it seemed that my presence would make a difference (a need to be important might be another way to put this); thus in Alaska in 1991, it was just me and two colleagues from the Anchorage Daily News (one a Native Alaskan) who marched in front of the federal building, holding up signs with frostbitten fingers. And so in Paris in 2003, I paraded with my fellow anti-war Americans towards the front of the march, where organizers usually placed us and where we were applauded by standersby, although once we were elbowed out of the way by militant organizers from the CFTD; the labor unions often seemed more interested in advertising themselves participating in marches than in advancing the actual causes.

For an American in Paris, taking part in these demonstrations held the extra lure of immersion in the rich Parisian lore of citizen insurgencies, inserting me into an earlier Paris history, as their itineraries often shadowed the storied Left Bank routes of the ‘soixante-huitards,’ the protestors of May 1968. It was also a way of re-living a San Francisco history which I had only experienced as a child and re-kindling that memory and spirit with the depth of adult consciousness. In many ways Paris – at least in the early 2000s, before the French malaise set in and the Parisian stress ratcheted up — for me was that: San Francisco in the ’60s, a way to live yesterday today with grown-up sensations.