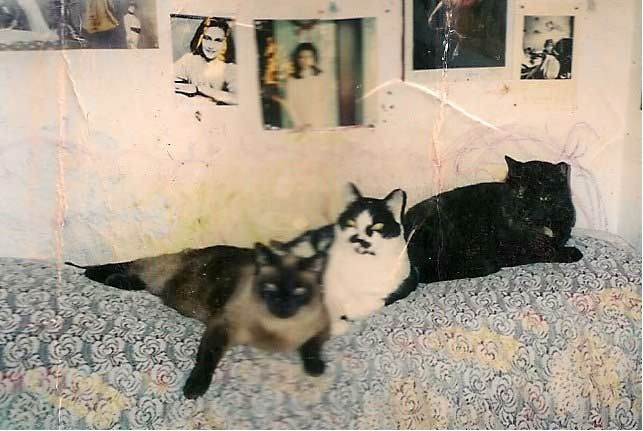

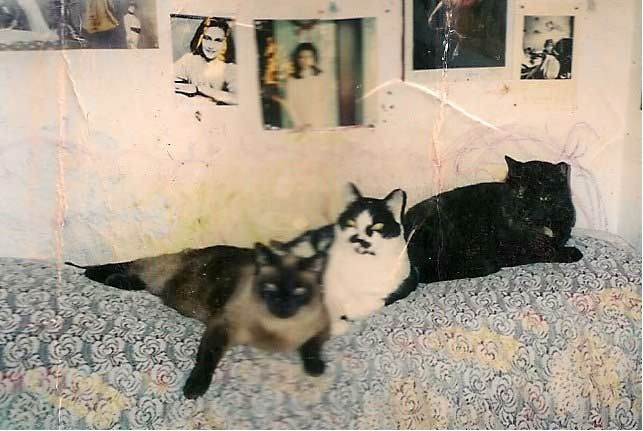

Les compagnons de la route: Sonia, Mesha, and Hopey, in our Greenwich Village digs next door to Electric Lady, where Jimi Hendrix and Carly Simon recorded. In the background, quelques muses: Sarah Bernhardt, Anne Frank, Mesha’s namesake, a dancer, and a photo by Roman Vishniac of Jewish children in Eastern European slums before the War.

By Paul Ben-Itzak Copyright 2011, 2016 Paul Ben-Itzak

‘Scuse me while I kiss the sky

“Je suis debout. Je suis vivante…. Ce n’etait que ma peur…cette idée dans ma tete qui m’empeche [de vivre], c’etait rien de tout. Des ombres. Des phantomes. Et des phantomes n’existe pas. Je suis vivante.”

“…. Je suis venu te proposé de tout refaire.”

—Lola Lafon

Pour V.

At the risk of hovering too long in the land of the dead — Paris being, to paraphrase Malcolm McLaren, a city of ghosts and shadows — I think it’s time to introduce my feline co-stars, the ones who made it possible for me to make all these traverses, from Alaska to San Francisco, San Francisco to New York, New York to Paris, Paris to Les Eyzies, the capital of pre-history for the first cro-magnon discoveries (more ghosts), Les Eyzies to Montpellier and Perigueux, and to Paris and back again twice: Sonia, Mesha, and Hopey, my compagnons de route for two decades of adventures and escapades.

I like to say that Sonia and Mesha were part wolf. This is because whenever I visited a home in Anchorage, where I adopted them in 1990, my host was likely to introduce the resident canine, usually a sorry-looking mongrel, as “part wolf,” as if he’d been rescued from the tundra. In fact I rescued Sonia and Mesha from the Anchorage SPCA. Sonia, a talkative chocolate-point Siamese who won my heart by batting her eyes at me from her cage, immediately and improbably hid behind the stove when we got home, and Mesha, a black-and-white European with requisite goatee, immediately pitched in to help me find her. Mesha liked to go out in the snow in front of our plain-pied, leaving tiny foot-prints in the fluffy white terrain while Sonia stood on the threshold of our apartment concernedly watching him until he stopped, petrified, and I retrieved him. As the sunlight dwindled and the cold increased — the local public radio station announcing the diminishing light each day (“Today is Monday, November 2. There are 5 hours, 37 minutes of daylight”) — the job, writing features for the Anchorage Daily News, turned out to be not what I expected, with no assignments to fly out to the Bush in view. This is not to say I didn’t learn anything.

Already, as a San Francisco-based correspondent for Reuters in the late ‘80s and ‘90s, I’d written some of the first stories on the AIDS pandemic to break internationally and nationally, interviewing women with AIDS, prisoners with AIDS, AIDS researchers including Don Francis – one of the first to identify the disease — and, most hearbreakingly, Brendan O’Rourke, one of the first children to be diagonosed and treated in the pilot AZT program for children, never to reach his seventh birthday. I remember flinching when Brendan jumped onto my lap, noticing a cut in his finger. I also remember doing a story on the AIDS Quilt and discovering, by reading his name on one of its patches — “Christian Perry: 1962 – 1982” – that a mate from high school had died of the big disease with a little name, the first I’d known personally to succumb. So in Anchorage, I decided I was going to be the first to break the story of AIDS in the Bush country. We put an announcement in the paper seeking AIDS victims to interview from the Native Alaskan villages, promising anonymity. I immediately got a call from Lorraine Porter, a worker with the Alaskan health service, begging me not to run the story. Explaining that anonymity was no shield in a village of 150 residents, Porter asked me a question that was to become a guardrail for me as a journalist: “What is your intention?” My editor argued that having won a Pulitzer prize for a series on alcoholism and suicide among the Natives, the Daily News was certainly sensitive to covering this community. The Natives, however, had a different idea: The series had stigmatized them. I also recalled doing a story for the West Wing, the newspaper of Mission High School in San Francisco, on immigrants, in which I shared a Phillipina classmate’s description of her brother coming home with a gun. “I wanted to destroy all the copies of the newspaper!” my distressed friend confronted me with when the story was published.

Having encountered narry a moose (although I did discover moose-nugget jewelry, made from dried moose-poop; and, as a colleague quipped, “and the moose never met you”) I scooped up my feline huskies and took them back to San Francisco, where they enjoyed 4 1/2 years as outdoor cats and we picked up a new family member, Hopey, a brainy tortoise-shell calico with an amplified purr I’d found at an SPCA adopt-a-cat stand on Powell and Market as a gift for a girlfriend who’d been unable to keep her.

With free-ranging privileges from our home base in one half of the house I’d grown up in in the Mission District — my retired architect father had turned the other half into an artist’s atelier where he created fountains and animated figures out of wood (that’s his atelier up top the Home page) — Sonia chalked up the first two of the 14 lives she would lead, surviving a leg wound sustained while scaling fences to return from her daily visit with the Burmese four backyards away, and miraculously not running out into busy 22nd Street traffic from the front of the garage where I found her nonchalantly observing the scene on returning from work one afternoon. Mesha also survived two close brushes with death involving his internal plumbing. Sonia, much to her own surprise, once caught a tall yellow cockateel, that continued squawking as she looked at me as if to ask, “Now what do I do with it?!”; at the exact same moment, Hopey tailed a rat until the rat turned around and started chasing her. (“How about if I put poison out for it?” I’d asked the person who answered the phone at animal control. “Why would you do that?” came the typicallly San Franciscan response. “That’s cruel.” Years later, when we lived in the country in Les Eyzies, rifle blasts coming my retired farmer neighbor Mr. Marty’s meant he had gunned down the rats invading his grange.)

Our NY adventure began in 1995, when we all descended on an apartment with bathroom down the hall on E. 88th Street and Lexington for a sublet with one very freaked out resident cat, a large tabby named Norton, who quickly found himself outnumbered by my three, who took turns hounding him. Most of the next six years were spent in a tiny tenement apartment on W. 8th Street in Greenwich Village, where famous cat neighbors included “Jimi,” the resident feline of Electric Lady Studios, right next door to us and the fabled mecca where not just Jimi Hendrix had held forth but, more significant for me, where Carly Simon had recorded “Anticipation,” which is what I hope I’ve left you with for the next chapter, when I return you to Paris after our move there in 2001 and, eventually, our demeure of six years on the rue de Paradis. ‘Scuse me while I kiss the sky.