By Paul Ben-Itzak

Copyright 2013, 2019 Paul Ben-Itzak

First published on the DI/AV on February 14, 2013.

If you think Butoh is the excruciatingly slow (or delectably languorous, depending on your point of view) dance interpreted by performers doused in flour that its Western acolytes have laid claim to with Zen-like fervor and wonder why this post-Hiroshima and Nagasaki art form was once called the ‘dance of darkness,’ Donald Richie’s 1959 “Sacrifice / Gisei,” being screened Sunday February 24 at Anthology Film Archives as part of its mini-festival of Film Experiments in 1960-70s Japan (meant to coincide with the Museum of Modern Art’s Tokyo 1955 – 1970: A New Avant-Garde exhibition closing Monday), will set you straight. The dance captured here is neither slow nor nuanced. Indeed, in a response typical of an ignorant Western critic, when the 8mm to video 10-minute piece opened (American so-called Butoh interpreters would take 10 minutes just to move a muscle), the performers running in circles and lifting their arms over alternating shoulders moved so gracelessly that at first I mistook the choreography for a paltry Japanese imitation of Judson, before I read the press release and realized that this Butoh authentically captured reveals the opposite, how diluted the ‘dance of darkness’ has become as it’s been transmitted by generations of non-Japanese interpreters. The film ends (spoiler alert) with young men and women happy-go-luckily pissing on (or raping, female on male), defecating on, and finally castrating an agonizing colleague. (Decidedly not a scene that would ever make it into today’s ‘family-friendly’ New York theaters.) (Sharing the bill with “Sacrifice” is the 1969 “Portrait of Mr. O,” the first in a series of collaborations between Chiaki Nagano and Butoh co-founder Kazuo Ohno.)

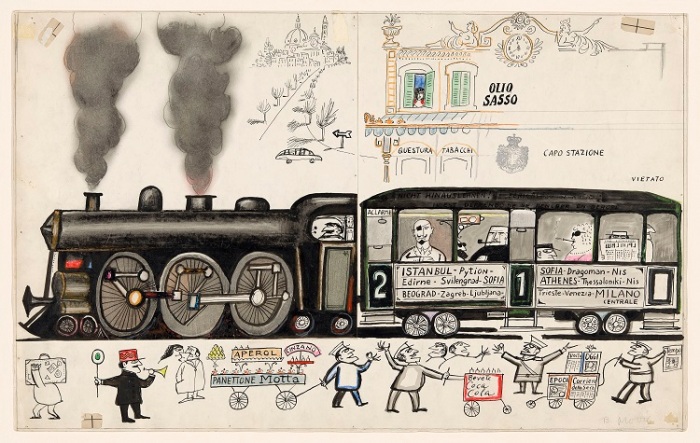

If you’re looking for something here to take the kids to, try Program 9 (Monday February 25), which is mostly cartoons, the ones I was able to screen most easily described as being composed in various fashions from and manipulations of cut-outs. Akira Uno’s 1965 “Toi et Moi / Omae to Watashi,” replete with fish and anthropomorphisms and set to baroque music, suggests where the French dance – filmmakers Montalvo-Hervieu might have found their animated ideas. But the gems here come from Tadanori Yokoo (who made them in 1963-64-65). After opening with the bon-bon “Kiss Kiss, Lichtenstein,” which applies flip-book technique to comics tableaux to create cut-away cartoons (animating the bisou), Yokoo delivers a tour-de-force riff on everything wrong and right with the Anglo hegemony of the era, a Peter Maxian extravaganza (although Yokoo here precedes “Yellow Submarine” by five years, so perhaps the former was inspired by the latter) clocking in at less than 10 minutes in which which “Alain Delon” (a dollar dangling from his mouth) and “Brigitte Bardot” are pursued and blasted to smithereens by the Beatles and a John Wayne-like figure on horseback, across the Manhattan sky-line, by jet bombers and submarines, until they find respite on a train bound for the peak of a volcano. There’s even a curtain-raiser performed by “Elizabeth Taylor” and and a scythe-wielding Richard Burton, and a cameo by Marilyn Monroe.

Katsu Kanai’s 1970 “Good-Bye” combines the sensibilities of the above-described two programs; so you could take the kids for the singing candy salesman (accompanied by drummer) hawking Japanese and other Asian bon-bons outside a Korean village, but then you’d have to cover their eyes for the graphic male on male and possible female on male rape scenes. The first was, I think, meant to represent Japan raping Korea, given that the PR describes “Good-Bye” as the first postwar Japanese film to be shot in South Korea, and an “absurdly comic but nevertheless poignant exploration of Japanese-Korean relations and the roots of the Japanese bloodline.” To decipher the geopolitical implications, I think your kid would need to be a scholar of the subject, so if you’re not, I suggest going for the surrealism that’s used to explore the theme. The not entirely linear (Eastern?) turn of events suggests that the viewer might be able to arrange his or her own chronology and even narrative of the micro if not the macro plot-line. It’s a sort of cylinder without an apparent beginning or end, an invitation to the kind of time-travelling hop-scotch Kurt Vonnegut designed in “Slaughterhouse Five.”

While I was unable to screen the film, its topicality in the wake of Fukiyama recommends Noriaki Tsuchimoto’s 1971 “Minimata: the Victims and their World / Minamata: Kanja-San to Sono Sekai,” screening Thursday, February 21. When the fertilizer company Chisso began depositing wastewater with traces of mercury into the nearby sea, residents of the town of Minimata started to show symptoms of what came to be recognized as a dangerous disease. Tsuchimoto follows the townspeoples’ struggle to receive a formal apology from Chisso.

What all these films have in common is they suggest a less-sanitized memory of an era which American popular culture media has been trying since the turn of the last century to turn into Valhalla, stripping the glossy veneer from the “Mad Men.”

Paul Ben-Itzak’s new 40-page Memoir, including art by Ansel Adams, Robert L. Berry, Lou Chapman, James Daugherty, Gustave Caillebotte, Jacob Lawrence, Sylvie Lesgourgues, David Levinthal, Roy Lichtenstein, Sam Peckinpah, Charles M. Russell, Saul Steinberg, and Frank Lloyd Wright from both current exhibitions and the AV Archives, is now available. To receive your own copy as a PDF or Word document, including 35 illustrations, please send $19.95 to the AV by designating your PayPal payment to paulbenitzak@gmail.com, or write us at that address to learn about payment by check. Your purchase includes a complimentary one-year subscription to the Arts Voyager and

Paul Ben-Itzak’s new 40-page Memoir, including art by Ansel Adams, Robert L. Berry, Lou Chapman, James Daugherty, Gustave Caillebotte, Jacob Lawrence, Sylvie Lesgourgues, David Levinthal, Roy Lichtenstein, Sam Peckinpah, Charles M. Russell, Saul Steinberg, and Frank Lloyd Wright from both current exhibitions and the AV Archives, is now available. To receive your own copy as a PDF or Word document, including 35 illustrations, please send $19.95 to the AV by designating your PayPal payment to paulbenitzak@gmail.com, or write us at that address to learn about payment by check. Your purchase includes a complimentary one-year subscription to the Arts Voyager and